Churchill and Tonypandy: Did he really shoot down striking miners?

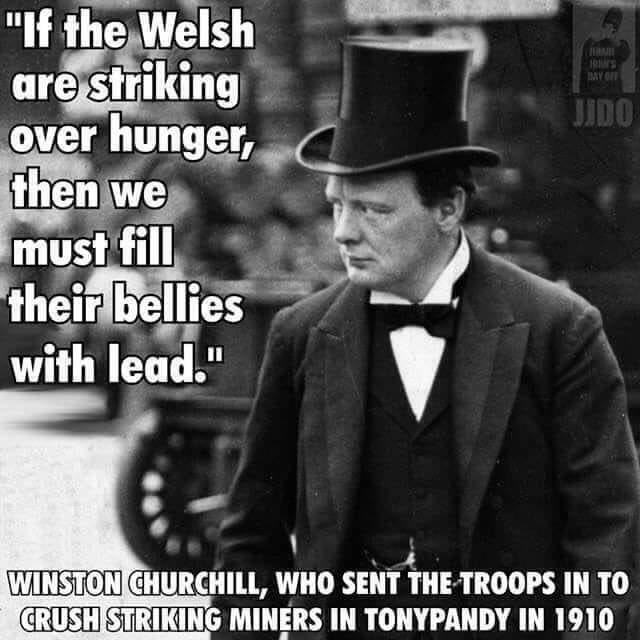

The controversy over Tariq Ali’s book Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes stirred renewed interest among the left in Churchill and his political record. That might explain why the above meme has been regularly shared on social media in recent months. It would appear to be the work of the same crank who composed the stupid image macros attacking Keir Starmer and Tom Watson that I’ve criticised in the past. As you might expect, given the source of the meme, the “fill their bellies with lead” quote is fake. It’s used to back up the long-debunked story that in November 1910, as home secretary in the Liberal government, Churchill despatched soldiers to shoot down striking miners in the Rhondda, where clashes between police and pickets culminated in the famous Tonypandy riot.

Among Churchill’s admirers, the inaccuracy of that charge has been exploited to dismiss all accusations that he was responsible for subjecting the strikers and their supporters to violent repression. In his 2014 potboiler The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History Boris Johnson sneered that his hero had “entered Labour’s demonology as the man who had ‘fired on’ unarmed miners in the Welsh town of Tonypandy — when in fact the police had used nothing more lethal than rolled-up mackintoshes”. Here Johnson was merely echoing the great man’s own claim, made during the 1950 general election campaign, that the police had confronted the strikers “not with rifles and bayonets, but with their rolled-up mackintoshes. Thus all bloodshed, except perhaps some from the nose, was averted and all loss of life prevented”.

Churchill even went so far as to assert that he had blocked any intervention at all by the military: “According to my recollection the action I took at Tonypandy was to stop the troops being sent to control the strikers for fear of shooting, and I was much attacked by the Conservative Opposition for this ‘weakness’. Instead I sent Metropolitan Police.” The same line is adopted in Randolph Churchill’s official biography of his dad, as excerpted on the International Churchill Society website, which cites a Times editorial condemning his failure to immediately send in the army as proof that “Churchill did not use troops against the miners”.

There is no question that Churchill was hesitant to deploy the military in a traditionally Liberal-voting area like the Rhondda, and that the troops despatched to the coalfield at the request of Glamorgan’s chief constable were initially held back on his orders. However, as Dai Smith notes in his article “Tonypandy 1910: definitions of community” (Past and Present 1980): “Churchill’s biographers have been too intent on translating his reluctance to become ‘Tonypandy’ Churchill — as another Liberal Home Secretary had become ‘Featherstone’ Asquith, after troops had shot two men at the Yorkshire Disturbances of 1893 — into an absolute unwillingness to use the military.”

Correspondence included in the 1911 Home Office report Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales shows that Churchill’s opposition to the use of troops didn’t last long. At 2.30pm on 8 November he states: “I have decided that cavalry shall be stopped at Cardiff for the present.” At 2.40pm he contacts the chief constable asking him to convey to the miners the message that “we are holding back the soldiers for the present and sending only police”. However at 8.10pm, after receiving news of attacks on shops in Tonypandy high street, Churchill wires the troops’ commander General Macready: “As the situation appears to have become more serious you should if the Chief Constable or Local Authority desires it move all the cavalry into the disturbed district without delay.”

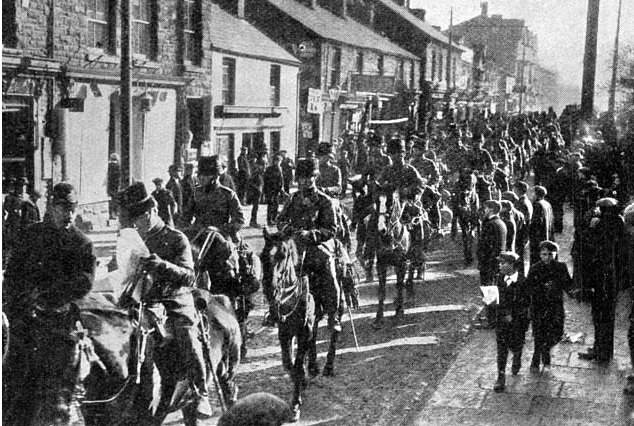

Macready later informs Churchill that a squadron of the 18th Hussars had arrived in Pontypridd by 10.30pm, and were joined by a second squadron at 8.15am the next day. One squadron was then sent to Llwynypia, the site of the colliery that the pickets were trying to close down, to the north of Tonypandy town centre. At 6pm on 9 November, following a telephone discussion with Macready, Churchill tells him: “In confirmation of our conversation I think it desirable that you should proceed to Tonypandy to-night as that seems to be the point where disturbances are most likely.”

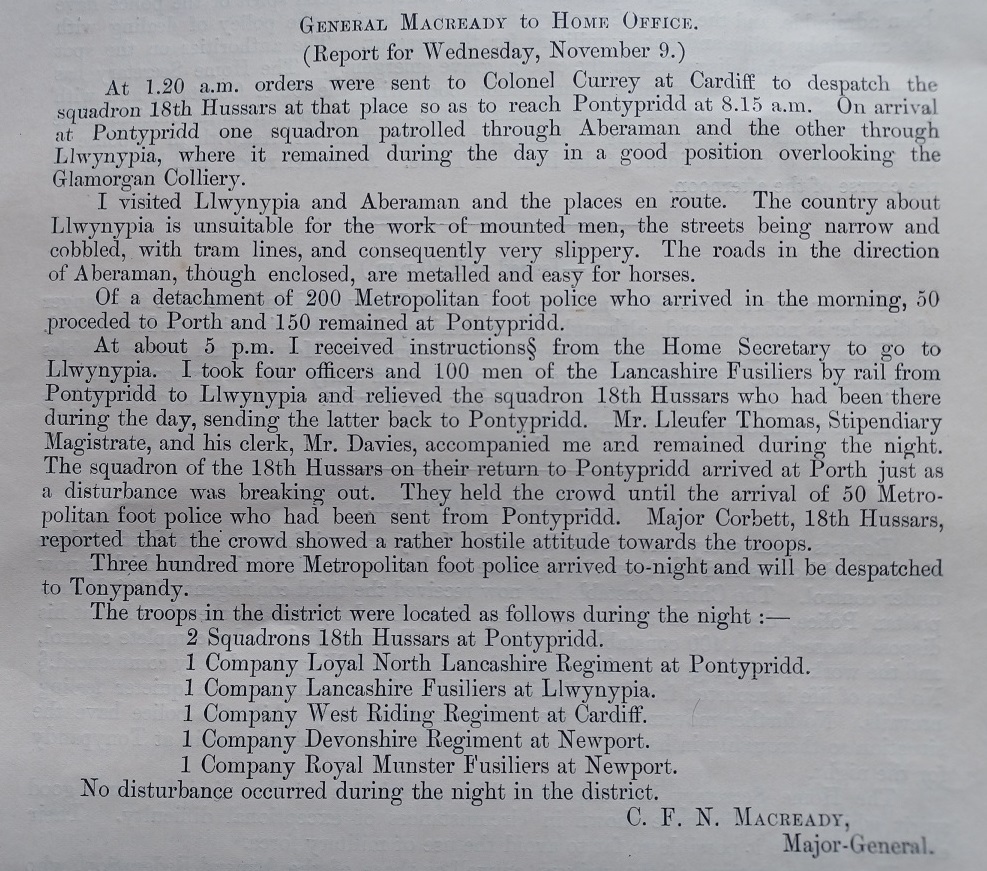

Macready’s report for 9 November, reproduced in Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales, gives the details of troop deployments at the end of that day, as authorised by Churchill. A company of the Lancashire Fusiliers was now stationed at Llwynypia, whose narrow cobbled streets were judged unsuitable for cavalry, while the two squadrons of the 18th Hussars were based at Pontypridd, a few miles down the valley, along with a company of infantry from the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. Three more infantry companies were held in reserve at Cardiff and Newport, close enough to provide reinforcements if they were required.

Dai Smith offers the following assessment of the role played by these troops in securing the coalowners’ eventual victory: “The Riot Act was not read in mid-Rhondda nor were any shots fired. On the other hand the troops were in attendance, in diminishing numbers, until the defeat of the strike in October 1911 and, more importantly, played a vital role in support of the large numbers of police, especially the well-trained Metropolitans, sent by the government after the initial vacillation over the troops. Together they constituted a formidable force.” In addition to the cavalry and infantry listed in Macready’s report, there were “over a thousand police, of whom a hundred and twenty were mounted. Infantry, using fixed bayonets, did assist the police in subsequent clashes”.

In his memoirs Macready himself describes how on one occasion the army intervened in support of the police to force stone-throwing strikers down from the hillside “by a little gentle persuasion with the bayonet”, as he puts it. He gives no further details. But we do know that in July 1911, during a demonstration over the use of scab labour, troops were directly deployed against the strikers. David Evans’ contemporary account Labour Strife in the South Wales Coalfield describes how a company of the Somerset Light Infantry surprised the miners “by appearing in extended order on the mountain top armed with fixed bayonets and ball cartridge. They carried their rifles in their hands, and when they were observed to be engaged in an enveloping movement the rioters fled. The troops drove the rioters into the town, where they were charged and dispersed.”

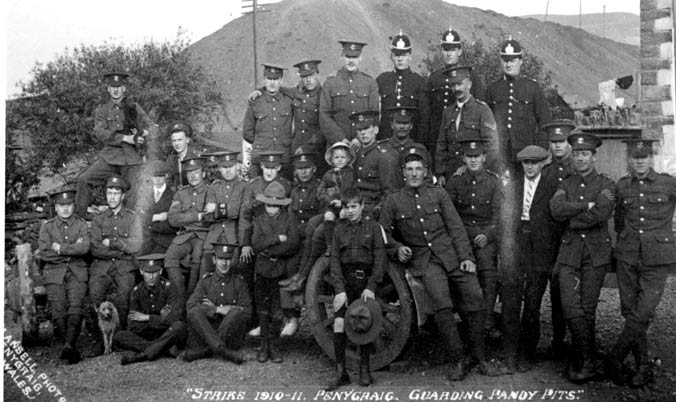

Active involvement by the military also resulted in some colliery premises being guarded jointly by police and troops. Macready’s staff officer Wyndham Childs refers in his own memoirs to troops being used to protect a colliery at Gilfach Goch. He and Macready “worked out manoeuvres whereby cavalry and infantry used to arrive suddenly at Gilfach, in the early hours of the morning, having take different routes. There was no question but that the population were impressed, and we had no more serious rioting there.” In this way the army’s presence served the purpose of intimidation without needing to come into direct conflict with the strikers.

In December 1910, when thirteen miners arrested during the disturbances were put on trial, Macready effectively placed Pontypridd under martial law, using infantry from the Loyal North Lancashire and West Riding regiments and the cavalry of the 18th Hussars, along with hundreds of police. The daily mass marches in solidarity with the accused, which drew up to 10,000 participants, were blocked from entering the town.

The crucial service that Macready provided to the coalowners was to enforce a ban on the mass picketing that could have resolved the dispute in the miners’ favour. He relates how he instructed the strike committee (which he claims, inaccurately, “consisted of half a dozen fanatical socialists, strongly impregnated with the theories of Karl Marx”) that picket lines should be limited to six men, and warned that if any more were present they would removed for causing obstruction. The Trade Disputes Act 1906 stated that “one or more persons” had a right to peaceful picketing and placed no restrictions on numbers, but Macready insisted that he had the power to impose his own rules. Pickets were even denied the right to a fire to keep themselves warm. Macready notes with satisfaction that by the end of November “picketing had practically ceased”.

Smith concludes: “The circumspect manner in which the military conducted themselves, along with Churchill’s desire not to offend a predominantly Liberal electorate whose annual miners’ gathering in 1908 he had personally attended, has obscured the fact that, in essence, the troops ensured that the miners’ demands would be utterly rejected.”

Tariq Ali’s account of these events in Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes relies heavily on Anthony Mòr O’Brien’s article “Churchill and the Tonypandy riots” (Welsh History Review 1994) which gives no credence to the story about Churchill ordering troops to shoot down striking miners. It does however reveal how correspondence from Churchill published in Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales was edited to remove evidence that he had called for the use of state violence against the strikers—not by the military, but by the police.

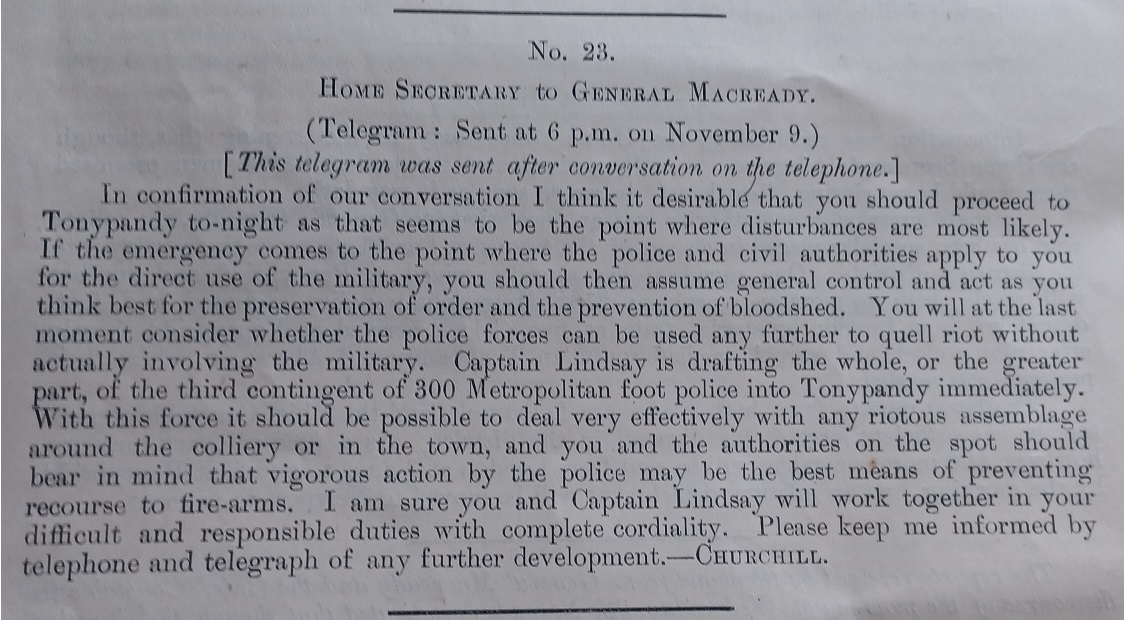

At issue is the telegram that Churchill sent to Macready on 9 November, which makes it clear that, contrary to the myth and the meme, Churchill was in fact arguing against troops being used to shoot the strikers. As can be seen from the published version of the telegram below, Churchill urged Macready to consider whether the police could be used to suppress rioting “without actually involving the military”. Informing Macready that a further three hundred Metropolitan police had been despatched to Tonypandy, Churchill continued: “With this force it should be possible to deal very effectively with any riotous assemblage around the colliery or in the town, and you and the authorities on the spot should bear in mind that vigorous action by the police may be the best means of preventing recourse to fire-arms.”

At least, that’s the version that appears in Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales. Anthony Mòr O’Brien provides the text of the original telegram, though, which puts a rather different slant on things. It reads: “With this force it should be possible to deal very effectively by police charges with any riotous assemblage around the colliery or in the town, and you and the authorities on the spot should bear in mind that vigorous baton charges may be the best means of preventing recourse to fire-arms.” The words in italics were edited out of the published version. O’Brien comments: “In a sense, Churchill was already laying the foundations for his later claim that the police used rolled-up mackintoshes rather than truncheons in dealing with the rioters.”

So the reality is that Churchill’s moderation in this case consisted in recommending the use of organised police violence against the miners as a substitute for soldiers shooting them. He was in fact encouraging a continuation of the methods that had already been applied on 7–8 November during the mass picketing at Llwynypia, when the strikers and their supporters were subjected to repeated baton charges by the police. David Evans’ Labour Strife in the South Wales Coalfield recounts how “scores of the rioters were struck down like logs with broken skulls and left on the ground”. One miner, Samuel Rays, was fatally wounded by a blow from “some blunt instrument” – obviously a police baton – and died in hospital from a fractured skull later that week. Churchill may have drawn the line at the army using firearms against the strikers but he was quite prepared to have the police beat their heads in.

Indeed, for all the subsequent emphasis on Churchill’s decision to send in the troops, it was police brutality that was the main cause of complaint at the time. Accusing the police of terrorising not just the strikers but the entire mining community, in both the Rhondda and neighbouring Aberdare valleys, Keir Hardie repeatedly called for an inquiry into their actions. “The charges are”, Hardie told Churchill, “that picketers were selected for attack, that children and women were attacked, that houses were broken into, that people coming out from the theatre were attacked, and that people who had been away the whole day from the neighbourhood and returned to their homes in the evening were attacked.”

But Churchill, no doubt anxious to avoid his own role coming under scrutiny, refused to hold an inquiry. Instead, to counter Hardie’s charges, Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales featured three pages of statements from selected eyewitnesses who all agreed that the police had acted “with great patience under extraordinary provocation” and “with great forbearance and leniency”.

Making misleading claims about Churchill’s use of the military at Tonypandy not only discredits his critics but also allows his apologists to avoid confronting his actual record during the strike and portray him as a man of peace smeared by ignorant leftists. It also serves to divert attention from the fact that the relative restraint Churchill showed in connection with the deployment of troops in the Rhondda was soon abandoned in the face of rising industrial unrest. Paul Addison’s very mainstream study Churchill: The Unexpected Hero is even more forthright than Tariq Ali’s book in its criticism of the ruthless repression directed by Churchill against militant workers. Addison writes:

“During the summer of 1911, when strikes in the docks spread to the railways, he was seized by a nightmare vision of a starving community held to ransom by industrial anarchists. Overriding the local authorities, he despatched troops to many parts of the country and gave army commanders discretion to employ them. When rioters tried to prevent the movement of a train at Llanelli, troops opened fire and shot two men dead. Churchill’s blood was up and when Lloyd George intervened to settle the strike Churchill telephoned him to say that it would have been better to go on and give the strikers ‘a good thrashing’. In a pamphlet entitled Killing No Murder Keir Hardie accused Asquith and Churchill of deliberately sending soldiers to shoot and kill strikers.”

In other words there are enough genuine reasons to condemn Churchill over his attacks on the labour movement during this period, without having to resort to the false accusation that he was responsible for shooting down Welsh miners, backed by a made-up quote about “filling their bellies with lead”.

Sources

Paul Addison, Churchill on the Home Front, 1900–1955 (1992)

Paul Addison, Churchill: The Unexpected Hero (2005)

Tariq Ali, Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes (2022)

Robin Page Arnot, South Wales Miners (Glowyr De Cymru): A History of the South Wales Miners’ Federation 1898–1914 (1967)

Wyndham Childs, Episodes and Reflections (1930)

Randolph Churchill, Winston S. Churchill: Young Statesman 1901–1914 (1967)

David Evans, Labour Strife in the South Wales Coalfield 1910–1911: A Historical and Critical Record of the Mid Rhondda, Aberdare Valley and Other Strikes (1911)

Gwyn Evans and David Maddox, The Tonypandy Riots 1910–1911 (1910)

Roger Geary, Policing Industrial Disputes: 1893 to 1985 (1985)

Home Office, Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales: Correspondence and Report: November 1910 (1911)

Boris Johnson, The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History (2014)

Nevil Macready, Annals of an Active Life, Volume 1 (1924)

Jane Morgan, Conflict and Order: The Police and Labour Disputes in England and Wales, 1910–1939 (1987)

Anthony Mòr O’Brien, “Churchill and the Tonypandy riots”, Welsh History Review (1994)

David Smith, “Tonypandy 1910: definitions of community”, Past and Present (1980)

David Smith, “From riots to revolt: Tonypandy and The Miners’ Next Step”, in Trevor Herbert and Gareth Elwyn Jones, eds, Wales, 1880–1914 (1988)

Barbara Weinberger, Keeping the Peace? Policing Strikes in Britain, 1906–1926 (1991)

First published on Medium in August 2022