Churchill and Tonypandy: Who was responsible for sending in the troops?

A while back I wrote a long article (“Churchill and Tonypandy: Did he really shoot down striking miners?”) analysing Winston Churchill’s role as home secretary during the events surrounding the Tonypandy riot of November 1910.

The condensed version is that, contrary to the still widely accepted myth, Churchill did not order the army to shoot striking miners at Tonypandy. After an initial vacillation he did however deploy the military against the strikers, along with a large force of Metropolitan police. This combination of police and military repression prevented the use of mass picketing, which the miners were relying on to win their demand for a living wage, and led to a protracted dispute that ended in defeat for the strikers. Although he urged the troops’ commander General Nevil Macready to avoid firing on the miners, Churchill advocated police violence as a substitute, doctored the official Home Office report to hide the fact that he had done so, refused to recognise clear evidence of police brutality against the mining community, and rejected calls by Keir Hardie for an official inquiry.

Since posting that article I’ve been involved in a few Twitter/X arguments with Churchill’s admirers, who go further than just rejecting the mistaken story about Churchill shooting striking miners and have obstinately refused to accept that he was responsible for the decision to deploy troops. Only the local authorities had the legal right to summon military aid to the civil power, the argument goes, and at Tonypandy it was the chief constable and/or the stipendiary magistrate who called in the military, not Churchill. It is also argued that, when Churchill instructed General Macready to move the army into what was termed the “disturbed district”, this order was superfluous, because Macready had already sent troops there on his own initiative before receiving Churchill’s message. In short, “Churchill didn’t order troops into Tonypandy”.

In this article I want to examine the events of 7–8 November 1910 in more detail than in the earlier piece, and will show that it was indeed Churchill who was responsible for the decision to send the troops in.

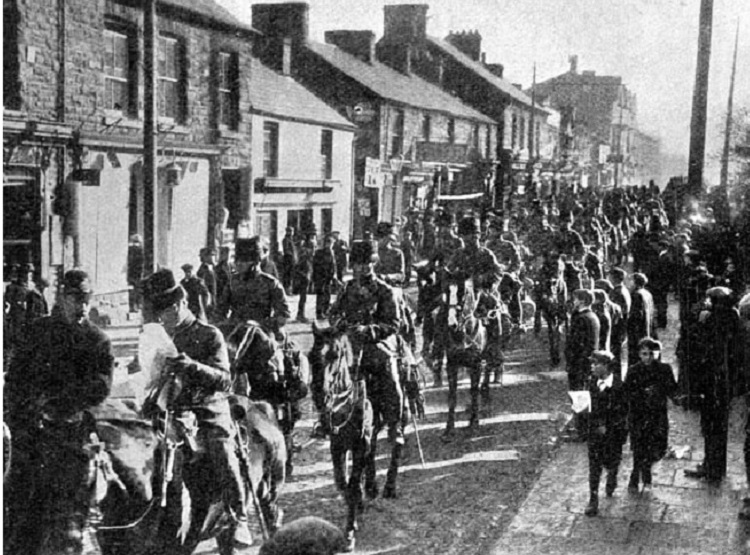

By early November twelve thousand miners employed at the Cambrian Combine collieries in the Rhondda were on strike in a bitter dispute over wage rates. Their strategy concentrated on shutting down the pumps operated by enginemen, stokers and other craftsmen who were not members of the main trade union, the South Wales Miners’ Federation, with the aim of forcing the mineowners to concede the strikers’ demands in order to avoid the pits flooding. So on Monday 7 November strikers, together with their wives and children, organised huge processions to each of the pits affected by the dispute calling for the cessation of all work there.

As Barbara Weinberger writes, the strikers and their supporters “by picketing in large numbers, but without resort to violence or destruction of property” successfully closed down all but one of the Cambrian Combine pits.1 That was the Glamorgan colliery at Llwynypia, just north of Tonypandy, where chief constable Lionel Lindsay decided to take a stand in defence of the coalowners, using not only local forces but also police he had drafted in from Bristol, Cardiff and Swansea. At 10.30pm a mass demonstration gathered outside the colliery. Stone-throwing by youths provided a pretext for an attack by police with truncheons, and the pickets were driven back into Tonypandy town centre where they were subjected to further baton charges and dispersed.2

At 1am on 8 November Lindsay sent telegrams to army bases at Shrewsbury, Chester and Salisbury Plain applying for military assistance, and at 3.30am he received confirmation from the headquarters of the British Army’s Southern Command at Tidworth that infantry and cavalry were on their way.3 Here Lindsay was following the procedure for summoning military aid to the civil power as recommended by the 1908 Select Committee on Employment of Military in Cases of Disturbance and set out in a Home Office circular of 1909. Having been signed by a magistrate, the requisition was to be checked by the chief constable and then sent to the military authority, with the secretary of state for war copied in. It was however the local magistrates and chief constable who were empowered to call in the army, not the War Office, and they were under no obligation even to contact the home secretary.4

Nevertheless, before the troops arrived, Lindsay did inform Churchill of his actions. In a telegram sent at 9am and received by the Home Office an hour later he wrote: “All [sic] the Cambrian collieries menaced last night. The Llwynypia Colliery savagely attacked by large crowd of strikers. Many casualties on both sides. Am expecting two companies of infantry and 200 cavalry today…. Position grave.”5 According to David Evans’ contemporary account Labour Strife in the South Wales Coalfield, Lindsay followed up the telegram with a phone call to the Home Office in which he conveyed to Churchill “his fear that owing to the hilly character of the district at and about the Glamorgan Colliery he would not be able with police alone to prevent another night attack on the pit”.6

In response to Lindsay’s alert Churchill immediately convened a meeting at the Home Office with war secretary Richard Haldane. Others in attendance were the adjutant-general Spencer Ewart, Home Office permanent secretary Edward Troup and Metropolitan Police commissioner Edward Henry.7 This conference resulted in Haldane ceding control of the operation to Churchill, thereby resolving a potential conflict of authority between the War Office and the Home Office. Troops were placed under the command of General Macready, who was called to the Home Office and apprised of the situation in the Rhondda (and in the neighbouring Aberdare valley, where miners were also on strike) before leaving for South Wales that afternoon. It was from Churchill, not Haldane, that Macready was to receive his orders.8

At 1.30pm Churchill telegraphed Lionel Lindsay to inform him of the decisions taken at the conference with Haldane. Overturning the principle that local authorities had the power to call in the military without requiring the permission of central government, it had been agreed that the infantry Lindsay had ordered would be held back at Swindon. But seventy mounted police (the actual number sent was a hundred) and two hundred foot police would be despatched to the Rhondda to augment the existing forces. Churchill anticipated that these additional police would be sufficient to maintain order, “but as further precautionary measure 200 cavalry will be moved into the district to-night and remain there pending cessation of trouble”. The military would not however be allowed to intervene against the strikers “unless it is clear that the police reinforcements are unable to cope with the situation”.9

As Nigel Morgans comments: “This intervention by Churchill was certainly not within the procedures previously detailed by Haldane himself as Secretary of State for War to the Select Committee in 1908 and seemed to be beyond his powers as Home Secretary. It is quite extraordinary how he managed to coerce Haldane into letting him take control of events.”10

Anthony Mòr O’Brien muddies the waters here by stating that it was “Haldane, not Churchill, who sent in the troops”.11 That was the case, but only in the technical sense that the home secretary had no right to issue orders to Southern Command regarding the deployment of troops. So it would necessarily have been Haldane who conveyed their joint decision to send in the cavalry. As already noted, this issue was resolved by placing the troops under the command of Macready, and Macready under the authority of Churchill. O’Brien also misquotes Haldane as telling the Commons on 15 November that troops “were sent at my insistence”.12 Haldane was in fact replying to Keir Hardie, who had asked at whose instance the soldiers were sent (i.e. on whose orders). What Haldane actually said was: “They were sent at my instance after careful consultation with my right hon. Friend the Home Secretary.”13

In his telegram Churchill had asked Lindsay to confirm the arrangements, and the chief constable phoned the Home Office at 2pm. Following a discussion, Churchill concluded that the police reinforcements would be sufficient to contain the unrest, without requiring a military presence in the “disturbed district” itself. He therefore decided to revise the plan agreed earlier with Haldane, and to instruct the cavalry to detrain at Cardiff, some eighteen miles from Tonypandy/Llwynypia.14 The obvious course of action would have been to issue an instruction to Macready, but at that point Macready couldn’t be contacted because he was en route to South Wales. So at 2.30pm Churchill telegraphed the adjutant-general at the War Office to tell him: “I have decided that the cavalry shall be stopped at Cardiff for the present. Please give orders accordingly, and inform me that this has been done.”15

Macready reached Cardiff at 6.30pm. From the start he adopted a sceptical attitude towards what he regarded as exaggerated claims about violent disorder, which were used to justify demands for immediate military intervention. He recounts that on his arrival “I was met by various military and police officials who struck me as being unduly perturbed by the reports that were coming in from Tonypandy”. Similarly, “the few officials I managed to get in touch with at Pontypridd seemed to have lost all sense of proportion, and to be obsessed with but one idea: to flood the valleys with troops”. Lindsay, who was at that point (see below) besieged by pickets at the Glamorgan colliery, “was naturally influenced by his immediate surroundings, and at the moment of no assistance towards helping to a general view of the situation”.16

Macready was surprised to find that, while he was on his way to Cardiff, Churchill had ordered the cavalry to stop there, which Macready considered “an unfortunate decision under the circumstances”. However at 6.40pm Churchill sent him a telegram stating that, although it was “hoped that cavalry will not have to proceed beyond Cardiff”, Macready could “use your discretion about going further”.17 Taking advantage of the authority delegated to him, Macready says he “arranged for one squadron to come on at once to Pontypridd”.18 His reasoning presumably being that in the event of troops being required to intervene against the strikers it would be better to have them stationed just six miles from Tonypandy at Pontypridd rather than a further twelve miles away in Cardiff. There is no indication that Macready intended the troops to advance beyond Pontypridd at this point.

Meanwhile a conflict even more intense than on the previous evening was taking place at Llwynypia where a mass demonstration had gathered around 6pm. Once again it appears that the clashes were provoked by police violence against the pickets, who responded in kind. Barbara Weinberger points out that the strikers and their supporters “were acting quite legally when they walked in orderly procession from Tonypandy to gather in large numbers (estimated at 7,000) outside the Glamorgan colliery” and that “the disturbances only began when mounted police attempted to disperse the crowd, thus creating the very disorder the police were supposed to prevent”.19

In his unashamedly pro-coalowner narrative Labour Strife in the South Wales Coalfield David Evans provides a lurid account of the conflict outside the Glamorgan colliery. He describes how, after the mounted police had failed to disperse the demonstration, Lionel Lindsay decided to launch an attack by truncheon-wielding foot police, against which the strikers defended themselves with the use of pickaxe handles, iron bars and other improvised weapons:

“With a dervish yell and batons drawn they dashed out between 80 and 90 strong from the colliery yard and cut a way clean through the densely packed mob…. Moving forward in solid bodies of two files they slowly but steadily drove the rioters ahead of them. Constantly the two sides were in furious combat. Using their formidable weapons with great effect the rioters on several occasions temporarily checked the forward movement of the police … but they had to give way to the determined resistance of a small body of determined men each of whom felt that he carried his life in his hand, and scores of the rioters were struck down like logs with broken skulls and left on the ground. The agony cries of the injured, the sharp hissing clash of baton against pick handle and other weapons, the sickening thud of skull blows, and the howling of a mob maddened with rage is better imagined than described.”20

For all its ferocity — one of the batoned pickets, Samuel Rayes, later died from a fractured skull — the battle was over fairly quickly. Piecing together the sequence of events from a number of sources, mainly local newspaper reports, Dai Smith describes how “fighting ceased outside the colliery at about 7.00pm” after a false rumour spread that cavalry were about to arrive by train. As a result “thousands of strikers” rushed to Tonypandy station to confront the expected troops. As they passed through the town’s main street “shop-windows were smashed in and some goods taken”. Around 8pm systematic looting of shops began and continued for two hours. This was facilitated by the absence of police on the streets, the forces defending the Glamorgan colliery having withdrawn to their base after fighting with the pickets ended.21 (The police despatched by Churchill from London were delayed and didn’t arrive until 10.30pm.)

At 7.45pm Pontypridd district’s stipendiary magistrate Lleufer Thomas — evidently one of those officials frustrated by Macready’s refusal to flood the valleys with troops — appealed to the Home Office in a telegram that painted a dramatic not to say wholly inaccurate picture of the situation: “Police cannot cope with rioters at Llwynypia, Rhondda Valley. Troops at Cardiff absolutely necessary for further protection. Will you order them to proceed forthwith.”22 As we have seen, the clashes in Llwynypia were in fact over by then and the police were standing down. The telegram does appear to confirm Macready’s point about local officials making exaggerated claims in an attempt to invoke military intervention. As it happens, Thomas’s request had no effect on the decision to deploy troops, because his telegram didn’t reach the Home Office until 9pm, by which time Churchill had already given orders to send the army in.

At 8.10pm, following a telephone report that that a riot was under way, Churchill sent a telegram to Macready stating: “As the situation appears to have become more serious you should if the Chief Constable or Local Authority desires it move all the cavalry into the disturbed district without delay.”23 We have no details as to who the telephone conversation was with, or what precise information was conveyed to the Home Office. Given that the phone call coincided with the onset of the collective looting of shops in Tonypandy high street, though, the obvious conclusion is that this was the “more serious” situation that Churchill was referring to, in response to which he overcame his hesitation about using the army.

To repeat the point — because it is ignored by Churchill’s admirers, and has escaped the attention of some historians — stipendiary magistrate Lleufer Thomas’s telegram had no bearing on Churchill’s decision to send in the troops. Indeed, at 9.15pm, after receiving Thomas’s by then redundant message, the Home Office replied: “Home Secretary has already authorized officer commanding cavalry at Cardiff to proceed without delay into disturbed district.”24

Speaking in parliament in February 1911, in the course of rejecting calls by Keir Hardie and other Labour MPs for an official inquiry into police violence against the miners, Churchill gave his version of the events on 8 November: “About eight o’clock telephonic communication was received that there was rioting in progress, and we immediately telegraphed to General Macready to move into the district with his squadrons, only one of which had up to that time arrived at Cardiff. He had already received authority to do so, and had, in fact, acted in anticipation of that message half an hour earlier.”25 This is used by Churchill’s defenders to absolve him of personal responsibility for sending in the troops. His 8.10pm telegram to Macready made no difference, it is argued, because by the time Macready received Churchill’s message the troops were already on their way to intervene against the miners. There is however no supporting evidence for Churchill’s claim that Macready had pre-empted his decision.

In reality, as we have seen, Macready’s own account indicates that he had firmly resisted calls from local officials for military action against the miners. The decision Macready took was only to move a squadron of cavalry to Pontypridd, between Cardiff and Tonypandy/Llwynipia. The decision to send the army into the “disturbed district” itself was Churchill’s, not Macready’s. As with much of the information Churchill provided about his role in the Tonypandy events, his statement to parliament was clearly and intentionally misleading.

It is evident from his correspondence with Macready that Churchill was aware he was on shaky ground legally in sidelining the local authorities and imposing central government control over the situation. It was also the case that Macready was inclined to treat the views of civilians with scant respect — his dismissive attitude towards local officials, including chief constable Lionel Lindsay, was evident on his arrival at Cardiff. Churchill was understandably anxious to avoid a damaging public row and therefore urged Macready to treat Lindsay diplomatically. Hence his qualifications along the lines of “if the Chief Constable desires it”. This should not be taken to mean that Churchill accepted the previously recognised right of the chief constable and local magistrates to determine the deployment of troops and police.

On the contrary, Anthony Mòr O’Brien argues that Churchill’s “hidden agenda” was that “Macready, on behalf of the Home Office, had to assert himself against the local police authorities”. Churchill’s views were outlined in a coded telegram sent to Macready on 14 November, which was unsurprisingly omitted from the correspondence published in the official Home Office report Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales. Churchill stated that he had instructed Lindsay to consult Macready before taking any action regarding the deployment of police. He told Macready that “you should therefore make your views prevail” over Lindsay’s, although if possible in such a way that the “Chief Constable will not be offended”. O’Brien comments: “Perhaps fortunately for Churchill, the situation developed in such a way that Lindsay was increasingly willing to defer to Macready’s authority. Centralism appeared to triumph over localism.”26

As Churchill’s biographer Paul Addison points out: “Traditionally, the maintenance of law and order had been a local responsibility…. Churchill’s appointment of General Macready to command both troops and police was an extraordinary constitutional innovation.”27 He cites the work of Jane Morgan, who similarly noted the unprecedented character of Churchill’s actions: “Unity of command of civil and military forces was being placed under a professional soldier, with Macready under the direct authority of the Home Office…. Churchill’s démarche thus completely overturned the existing procedure for riot control.”28 Like his future admirer Boris Johnson, Churchill took the view that the rules didn’t apply to him.

This became even clearer during the transport strikes of 1911. Addison outlines Churchill’s ruthless centralist response: “Overriding the local authorities, he despatched troops to many parts of the country and gave army commanders discretion to employ them. When rioters tried to prevent the movement of a train at Llanelli, troops opened fire and shot two men dead. Churchill’s blood was up and when Lloyd George intervened to settle the strike Churchill telephoned him to say that it would have been better to go on and give the strikers ‘a good thrashing’.”29 In reply to charges by Keir Hardie and others that he was arrogating to himself powers that he did not possess as home secretary, Churchill asserted that the army regulation that troops could not be sent in until there had been a requisition from the local authority had no legal force. It was “only a regulation for the convenience of the War Office and generally of the Government and has in these circumstances necessarily been abrogated”.30

For Jane Morgan, Churchill’s centralising actions at Tonypandy and subsequently marked the beginning of a shift towards greater control by the Home Office: “Industrial disorder of this kind was seen for the first time as a national emergency, one that required a co-ordinated response, civil and military, from the state.”31 Barbara Weinberger disputes Morgan’s analysis, arguing that this centralising tendency was a distinctive feature of Churchill’s tenure as home secretary, which came to an end in October 1911: “But once Churchill had left, the Home Office relapsed into its customary passivity as far as provincial policing matters were concerned.”32 What is not in dispute among historians, though, is that Churchill imposed central control over the use of police and army in the industrial conflicts of the period. In short, Churchill did order troops into Tonypandy.

Notes

1. Barbara Weinberger, Keeping the Peace? Policing Strikes in Britain, 1906–1926 (1991), p.48

2. Robin Page Arnot, South Wales Miners (Glowyr De Cymru): A History of the South Wales Miners’ Federation 1898–1914 (1967), p.186

3. Page Arnot, South Wales Miners, p.186

4. Jane Morgan, Conflict and Order: The Police and Labour Disputes in England and Wales, 1910–1939 (1987), p.40; Nigel Morgans, The Military Response of the Authorities to the Industrial and Civil Unrest in South Wales c.1910–11, MA dissertation (2013), p.11

5. Home Office, Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales: Correspondence and Report: November 1910 (1911), p.4

6. David Evans, Labour Strife in the South Wales Coalfield 1910–1911: A Historical and Critical Record of the Mid Rhondda, Aberdare Valley and Other Strikes (1911), p.43

7. Colliery Strike Disturbances, p.4

8. Macready recalled that, with the exception of technical military matters, he “came under the direct authority of the Home Office” as soon as he left London. See Nevil Macready, Annals of an Active Life, Volume 1 (1924), p.137

9. Colliery Strike Disturbances, p.4

10. Morgans, Military Response, p.29

11. Anthony Mòr O’Brien, “Churchill and the Tonypandy riots”, Welsh History Review (1994), p.79

12. O’Brien, “Churchill and the Tonypandy riots”, p.78

13. Hansard, HC Deb. 15 November 1910, vol.20, col.3

14. Colliery Strike Disturbances, pp.4–5. The decision is presented as having been taken on Lindsay’s initiative, rather than Churchill’s, which is hardly convincing given the chief constable’s “frenetic demands for troops and more troops post-haste”, as O’Brien puts it (“Churchill and the Tonypandy riots”, p.77).

15. Colliery Strike Disturbances, p.5

16. Macready, Annals, p.138

17. Colliery Strike Disturbances, p.5

18. Macready, Annals, p.139

19. Weinberger, Keeping the Peace?, p.49

20. Evans, Labour Strife, pp.46-7

21. David Smith, “Tonypandy 1910: definitions of community”, Past and Present (1980), pp.165-6

22. Colliery Strike Disturbances, p.6

23. Colliery Strike Disturbances, p.6

24. Colliery Strike Disturbances, p.6

25. Hansard, HC Deb. 7 February 1911, vol.21, col.230

26. O’Brien, “Churchill and the Tonypandy riots”, p.80

27. Paul Addison, Churchill on the Home Front, 1900–1955 (1992), p.145

28. Morgan, Conflict and Order, pp.45–6

29. Paul Addison, Churchill: The Unexpected Hero (2005), p.54

30. Morgan, Conflict and Order, p.55; Hansard, HC Deb. 22 August 1911, vol.29, col.2286

31. Morgan, Conflict and Order, p.46

32. Weinberger, Keeping the Peace?, p.113

First published on Medium in March 2024