‘Give the pop stars a fairer share of the country’s wealth!’ The Beatles and the Taxman

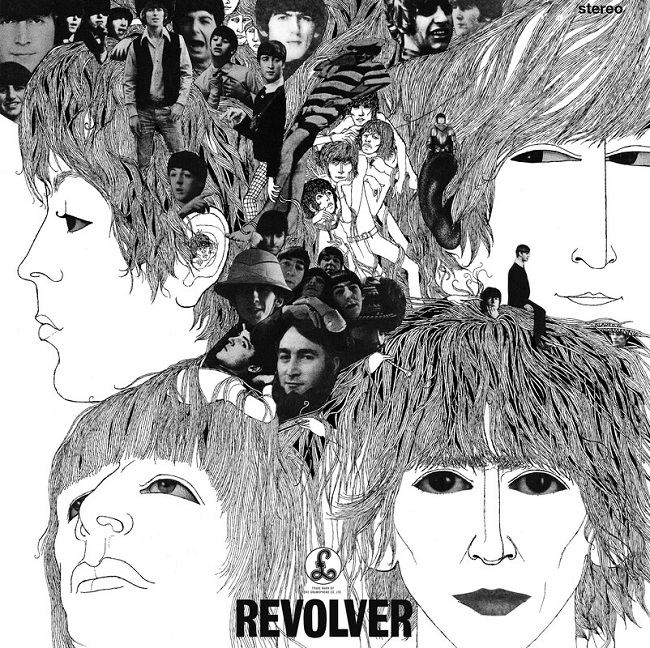

The reissue of Revolver in a new and expanded edition, fifty-six years after its original appearance, has reinforced my view that it is by far the Beatles’ best album, superior even to its successor, the generally more highly regarded Sgt Pepper. It also revived my annoyance at the first track on the album, the George Harrison composition Taxman.

A driving up-tempo number notable for Paul McCartney’s Motown-inspired bass playing and aggressive “Indian style” guitar solo, musically Taxman is a powerful opener to Revolver. The problem is with the lyrics. Harrison used the song to mount a bitter attack on the taxation policy of Harold Wilson’s Labour government, which was pursuing the admirable aim of rebalancing the tax system so that the rich made a greater contribution to the public finances. As the Labour Party’s 1966 election manifesto put it: “Among the worst injustices has been the heavy weight of taxation on the average citizen and the very light burden which, as a result of tax avoidance and other devices, is borne by those best able to shoulder it.” In line with this approach, for the 1965–66 financial year the government had raised the rate of tax from 90 percent on annual income over £2,000 (equivalent to £436,000 in 2022) to 95 percent on income over £1,500 (£327,000 today).

John Lennon helped with the lyrics to Taxman, and the song would have been more explicitly anti-Labour had it not been for the inclusion at his suggestion of the backing vocal “Ah ha Mr Wilson, Ah ha Mr Heath”, which rather incongruously held Tory Party leader Edward Heath equally responsible for the government’s assault on the Beatles’ earnings. (Heath wouldn’t become prime minister for another four years, following which his government — as a favour to the Tories’ wealthy supporters — reduced the top rate of income tax.) Although Lennon’s addition to the lyric didn’t make much sense, it did have the effect of blurring the actual party-political target of Harrison’s anti-socialist rant.

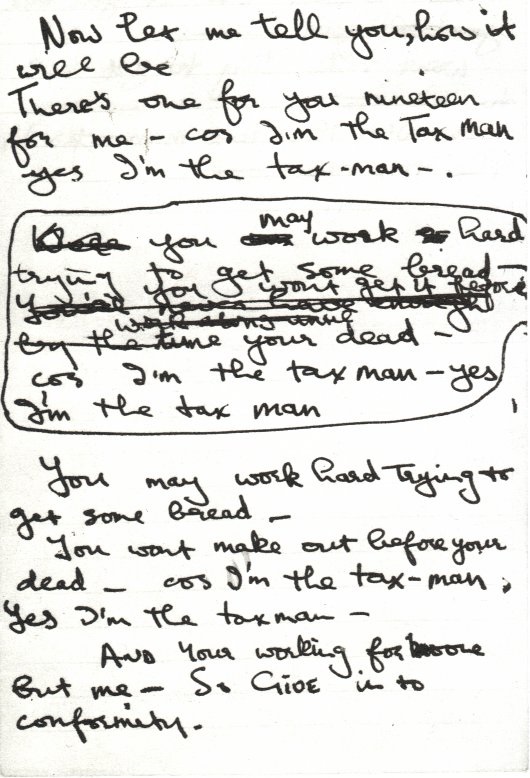

In his 1980 memoir, appropriately titled I Me Mine, Harrison recalled that he wrote Taxman “when I first realised that even though we had started making money, we were actually giving most of it away in taxes; it was and still is typical. Why should this be so?” Was it a form of punishment, Harrison wanted to know. His focus in 1966 was on what he believed to be the injustice of the increase that had raised the top rate of tax to 95 percent::

Let me tell you how it will be There’s one for you, nineteen for me ’Cause I’m the taxman, yeah, I’m the taxman Should five percent appear too small Be thankful I don’t take it all ’Cause I’m the taxman, yeah, I’m the taxman

The tax rate Harrison objected to obviously applied only to the very wealthy, a socio-economic category to which the Beatles now firmly belonged, with the high-spending lifestyle that went with it. Following the familiar path of the nouveau riche, they had (with the exception of McCartney, who preferred to remain in central London with access to the capital’s cultural life) purchased large properties for themselves in the stockbroker belt. Harrison’s own home since 1964 had been a luxury bungalow in Esher named Kinfauns (where the demos for the White Album would later be recorded) and in 1970 he moved to the more grandiose residence of Friar Park in Henley-on-Thames. So the Beatles were hardly living in penury. When they did hit financial problems in the late 1960s it was the result of their own poor business decisions rather than punitive taxation by the Labour government.

In The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology Walter Everett contrasts Taxman unfavourably with the album’s second track, the McCartney-composed Eleanor Rigby. Both the titular character and Father McKenzie who buries her, he writes, “are sad in their loneliness and in the obvious futility of their lives, the poetry carries a ‘Nowhere Man’-like extension of their condition to all of humanity, and McCartney’s images are vivid and yet common enough to elicit enormous compassion for these lost souls. Conversely, only those in the highest earning brackets would be likely to feel an overwhelming compassion for the ultrarich victims of Harrison’s Taxman.”

A revealing insight into the Beatles’ attitude towards the issue of taxation was provided in an interview with Radio Caroline DJ Tom Lodge in March 1966 at Oluf Nissen studio in London, where the group had gathered for the session with photographer Robert Whitaker that produced the notorious “butcher” cover for the US Yesterday and Today album.

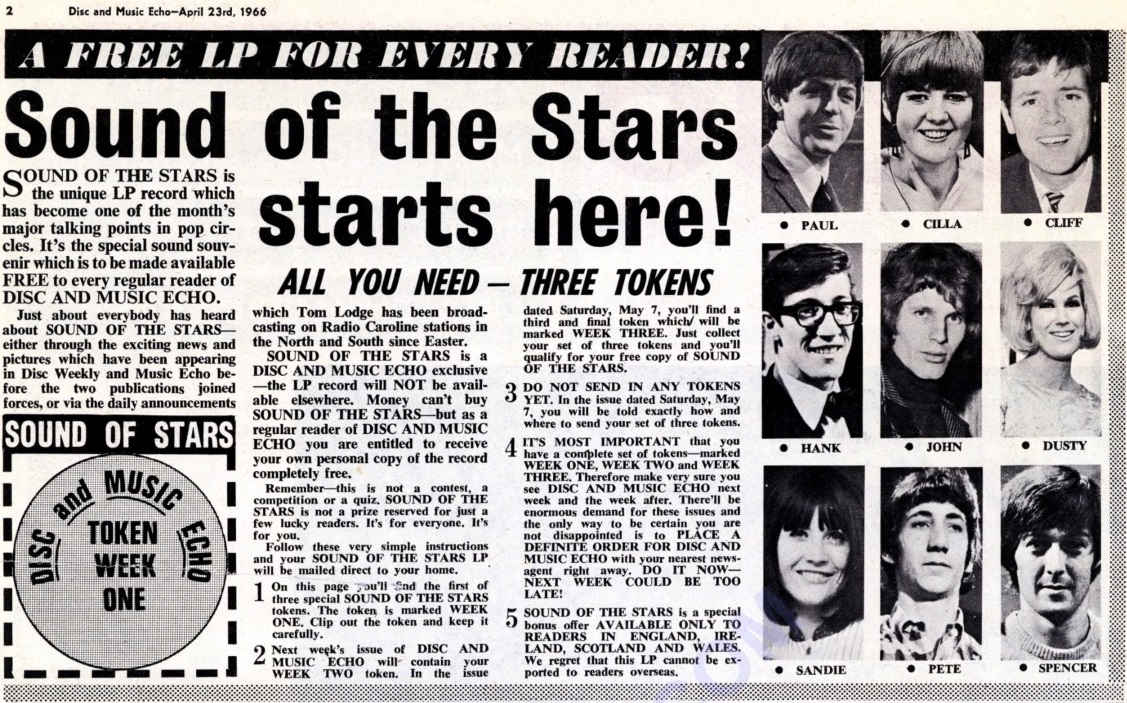

The interview was part of a promotional campaign for the newly launched publication Disc and Music Echo, the product of a merger between the pop music paper Disc and Beatles manager Brian Epstein’s own Music Echo (which itself incorporated the now defunct Mersey Beat). To encourage sales, readers who collected tokens from the first three issues of the new title could exchange them for a free 7-inch flexi-disc, Sound of the Stars, which featured interviews with a number of musicians, including the Beatles.

Only a short excerpt made it onto the flexi-disc, but Lodge retained a recording of the full 20-minute interview which later found its way onto a bootleg (a transcript can be read here). It was a rather chaotic affair. The Beatles were probably resentful at being roped into an advertising campaign for one of Epstein’s business ventures, and were disinclined to be cooperative, while Lodge didn’t appear to have taken the trouble to prepare any questions in advance.

The interview took place less than a week before a general election that was to result in the return of Wilson’s Labour government with an increased majority. Yet, despite being pressed by Lodge, none of the Beatles had anything intelligent to say on that subject. An attempt to draw them out on wider social issues did however result in the following exchange with Lennon:

Lodge: Do you — do you have any ideas of — you like to change this country in any way? Lennon: Yes, like to change it a lot. Lodge: In what way? Lennon: Well, the tax problem. Lodge: What would you do with the tax? Lennon: Well, I’d reduce it drastically. Lodge: That’s if your — you were Chancellor of the Exchequer. Lennon: No — if I was anybody. I’d reduce it. Drastically.

This was the UK in 1966, remember. A study the previous year had found that despite the post-war economic expansion 14 percent of the population (7.5 million people) lived in poverty. There was a housing crisis, soon to be highlighted in the TV play Cathy Come Home, with three million families living in slums or grossly overcrowded conditions. A rise in racism had been partially countered by the Race Relations Act 1965, but that still failed to deal with discrimination in employment and housing. In criticism of the Labour government Wilson’s refusal to oppose the US war in Vietnam might legitimately have been raised. So there were any number of changes that could have been proposed at that time, from a progressive political standpoint. For Lennon, though, the overriding issue was the alleviation of his personal tax burden.

Evidently embarrassed by his bandmate’s self-centred reply to Logan’s question, McCartney tried to make a joke of it by interjecting sarcastically: “Give the pop stars a fairer share of the country’s wealth!” He at least could grasp that very rich people complaining about not being rich enough wasn’t a good look. (In another March 1966 interview McCartney pronounced himself well satisfied with his new level of affluence. No longer needing to pursue commercial success, he argued, the Beatles now enjoyed the financial freedom to follow their creative impulses: “At first we wanted to make money, now we’ve got it, a fantastic platform of money to dive off into anything.”)

To be fair to Harrison, unlike Lennon he did relate the issue of high taxes to military spending. “But they can’t … take the taxes down, ’cause they haven’t got enough money”, he told Lodge. “And, uh, they’ll never have enough money while they’re buying all that crap like F111’s.” (The reference was to a US combat aircraft for which the government had placed a multi-million-pound order, later to be cancelled on grounds of cost.)

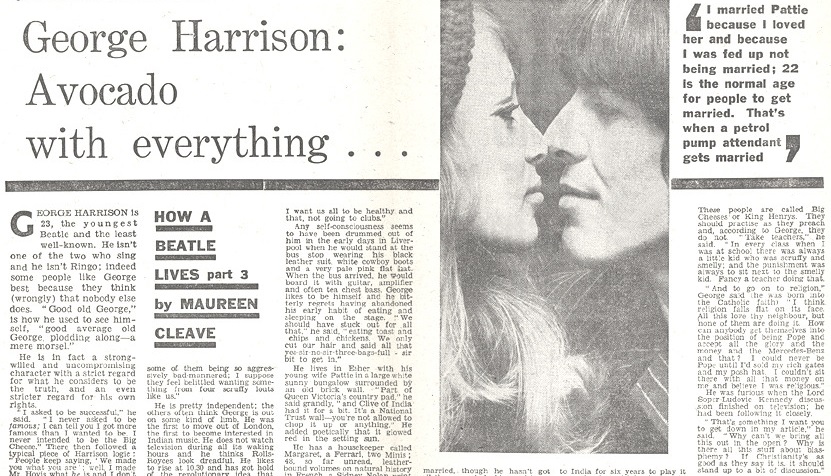

Harrison had made the same point a week earlier in an interview with Evening Standard journalist Maureen Cleave (as part of the “How a Beatle Lives” series, famous for the Lennon interview in which he stated “we’re more popular than Jesus now”). Cleave reported that Harrison’s views “are disconcertingly simple. He thinks that his, George’s personal taxes are going directly to pay for F111’s. He sees Mr. Wilson, the Prime Minister of England, as the Sheriff of Nottingham, ‘Taking all the money,’ he said, ‘and then moaning about deficits here, deficits there — always moaning about deficits’.”

There was nothing wrong with opposing excessive state expenditure on armaments. As Taxman demonstrated, however, the conclusion Harrison drew from this critique was not that the taxes raised by the government to pay for military hardware should be diverted to more socially useful purposes instead. Rather, he believed they should be diverted back into his own pocket.

Lennon for his part persisted in defending the indefensible. In December 1968 a Dutch TV interviewer complimented him on having taken a stand against the Vietnam war but said he had been “angry” at Lennon over the reactionary sentiments expressed in Taxman. Apparently taken aback that anyone could object to a song dedicated to upholding the privileges of the rich, a defensive and clearly irritated Lennon justified Taxman’s message as “anti-Establishment”. The Beatles had the right to keep what they earned, Lennon argued, “unless there’s a communal or communist or Christian — real Christian — society”. Short of that fundamental change in the social order, he declared, “I protest against paying the government what I have to pay them”. The idea that the redistribution of wealth through progressive taxation could be used to improve people’s lives in the here and now was lost on Lennon.

Ringo, it should be added, was no better. Interviewed for Hunter Davies’ 1968 book The Beatles: The Authorised Biography, he outlined his own anti-socialist political philosophy. Asserting that the railways had been more efficient when run by private companies, Ringo rejected state intervention and public ownership. (Which was rather ironic, given that he would likely have died in childhood if it hadn’t been for the National Health Service.) So it came as little surprise to hear that he was no more a fan of progressive taxation than Lennon and Harrison were: “The government takes too much in taxes. There’s no initiative, you get taxed right through life. When they’ve left nobody rich, no one will have any money to give the government.”

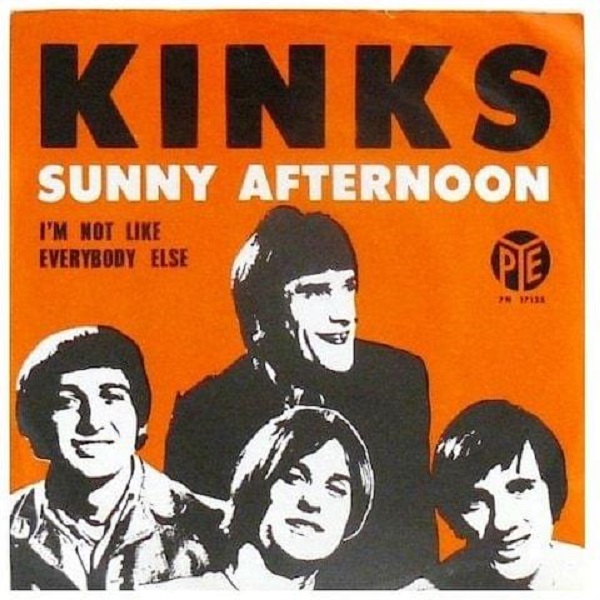

Ian MacDonald’s book Revolution in the Head: The Beatles Records and the Sixties draws a useful comparison between Taxman and the Kinks’ song Sunny Afternoon, which was written and recorded around the same time and similarly addresses the theme of the Labour government’s fiscal policy. Adopting the persona of a dissolute aristocrat, composer Ray Davies sings that the “the taxman’s taken all my dough”, leaving him alone in his stately home with only a cold beer on a sunny day to relieve his suffering.

MacDonald’s suggestion that Davies used this persona to skirt around the dilemma of a well-remunerated pop star griping about high taxes is confirmed by Davies in his autobiography X-Ray, where he explains: “As this was my first year of being a success, I could sympathize with the sad, decadent character I had invented. I was brought up believing that all Conservatives were cruel slave-drivers who took advantage of the poor and cared little for the unfortunates on whom their whole financial empire had been built. Here was I, newly rich (on paper), singing about the woes of having money taken away from me by a Labour Government.”

Davies therefore “turned the narrator into a scoundrel who fought with his girlfriend after a night of drunkenness and cruelty”. The character’s self-pitying complaint that “I can’t sail my yacht” would have further alienated any listener inclined to identify with his claims of oppression and deprivation at the hands of the Inland Revenue. Reflecting the ambiguities of Davies’ personal feelings on the question of taxation, Sunny Afternoon brought a self-awareness and sense of irony to the subject that was entirely absent from the Beatles’ Taxman.

First published on Medium in October 2022