Inciting hatred against Muslims — why we need a change in the law

On Monday an English Defence League sympathiser from Shoreham by the name of Nigel Pelham (pictured) received a 20-month prison sentence, having been convicted on eight counts of publishing threatening written material with the intention of stirring up religious hatred.

On Monday an English Defence League sympathiser from Shoreham by the name of Nigel Pelham (pictured) received a 20-month prison sentence, having been convicted on eight counts of publishing threatening written material with the intention of stirring up religious hatred.

In 2015 he had posted comments on his Facebook page such as “what this country needs is a bomb a mosque day” and “we must burn mosques to the ground”. Pelham claimed that he was a “nationalist” but not actually a member of the EDL (which of course has no formal membership). However, the prosecution stated that he had posted videos of EDL rallies on Facebook and had “sympathies if not support for” their views.

Although Pelham’s imprisonment provoked outrage from Islamophobes, to the rest of us it was welcome news that a far-right bigot had been jailed for inciting hatred against Muslims. Particularly so, given that his sentencing took place against the background of the terrorist attack at the Muslim Welfare House in Finsbury Park, which was carried out earlier the same day. The prison sentence will have served as a warning to supporters of groups like the EDL that their vicious propaganda, which provides the ideological inspiration for acts of anti-Muslim violence, will not be tolerated. To put Pelham’s conviction in context, though, so far as I’m aware he is to date the only far-right bigot to have been convicted of incitement to religious hatred. The reason for this is that the existing religious hatred law is seriously flawed.

It was back in 2005 that the then Labour government sought to introduce legislation criminalising incitement to religious hatred. They did this in order to end the anomaly whereby adherents of faiths defined as mono-ethnic (Jews, Sikhs) were protected under the racial hatred law, but adherents of faiths defined as multi-ethnic (notably Muslims) were not. This loophole left racists and fascists free to incite hatred against Muslims in a way that would have resulted in prosecution under the racial hatred law if they had used the same terms to attack Jews. In its original form the Racial and Religious Hatred Bill just went through Part 3 of the Public Order Act and where this referred to “racial hatred” it inserted the words “and religious”.

Unfortunately the bill was wrecked in the House of Lords through the adoption of an amendment drawn up by the Liberal Democrat peer Lord Lester, and it was subsequently passed by the House of Commons in its amended form to become the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006. (Regrettably, this was done with the support of some left-wing Labour MPs such as Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, who backed Lester’s sabotage of the bill.) Lester’s amendment added a new Part 3A to the Public Order Act dealing specifically with religious hatred (later expanded to include homophobic hatred too). This required both that the prosecution should prove intent and that the words and actions should be “threatening”, neither of which is necessary to secure a conviction for racial hatred under Part 3.

The requirement to prove intent was a major flaw in the original racial hatred law that was brought in as part of the Race Relations Act 1965. An organisation rejoicing in the name of the Racial Preservation Society was prosecuted under that law in 1968 for distributing a racist newsletter attacking Black immigration. While the publication clearly had the effect of inciting racial hatred, the RPS denied that this was their intention. Their purpose, they piously assured the court, was merely to inform the public and politicians about the dangers of immigration. The prosecution was unable to prove otherwise and the defendants were acquitted. Consequently, the Race Relations Act 1976 removed the requirement to prove intent; it was enough that racial hatred was “likely to be stirred up”.

Even worse is the requirement under the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 that the words or actions that stir up religious hatred have to be threatening, whereas under the racial hatred law the incitement of hatred by means of “abusive or insulting” words or actions is also a criminal offence. Under current legislation it is therefore possible for a far-right group or individual to produce propaganda that clearly has the effect of inciting religious hatred. They can even admit that they have done this with the intention of inciting religious hatred. However, as long as they avoid any explicit threats, they can’t actually be successfully prosecuted for inciting religious hatred.

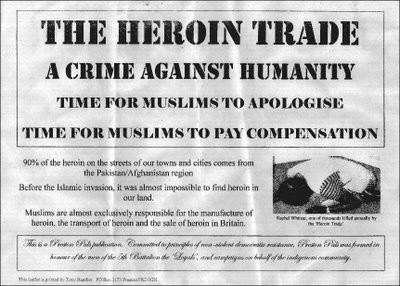

The absurdity of the present legal position was demonstrated back in 2009–10, when a British National Party activist named Tony Bamber was charged with incitement to religious hatred after distributing some 30,000 copies of a leaflet which claimed that “Muslims are almost exclusively responsible for the manufacture of heroin, the transport of heroin and the sale of heroin in Britain”. In fact the leaflet held the entire Muslim community responsible for the scourge of heroin addiction. It declared:

“From wives to corrupt politicians, from unscrupulous mullahs to Islamic travel agents, the mega-profits of The Heroin Trade has made Muslim colonies across the western world fabulously wealthy. Muslims do nothing to abolish this trade because they love money far more than they love their neighbour. Let nobody forget that before the Islamic invasion of ‘the west’ it was virtually impossible to find heroin in Britain.”

The effect of the leaflet was clearly to incite hatred against Muslims, and if the same sort of language had been directed against the Jewish community a prosecution under the racial hatred law would almost certainly have succeeded. However, given the weakness of the religious hatred legislation it was always unlikely that Bamber would be convicted. And so it turned out.

In her directions to the jury the judge told them, entirely accurately, that they were obliged to “to consider if the words were threatening, not abusive, insulting or upsetting”. She added: “Mr Bamber says that his intention was to publicise his campaign with no intention to stir up religious hatred. You must be sure that when he did the act of distribution, he intended to stir up religious hatred.” Unsurprisingly, as intent could not be proved and the leaflet contained no actual threats, the jury acquitted Bamber.

So it’s not difficult to understand why few convictions have been secured under the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006. Nigel Pelham was stupid enough to express his hatred of Muslims in such an extreme form that he was unable to claim absence of intent or, crucially, that his words were not threatening. With any luck, his conviction will set a precedent for further prosecutions of ignorant far-right trolls who incite violent hatred on social media. Organised far-right groups, and the more clued-up Islamophobes who lead them, however, have a better understanding of the law and are less likely to make the same mistake.

The solution is quite straightforward. It is to amend existing legislation to bring the rest of the UK into line with Northern Ireland, where there is an all-purpose anti-hatred law, formulated in the same terms as Part 3 of the Public Order Act (i.e. without the necessity to prove intent or the requirement that the words or actions should be threatening). This law provides equal protection against incitement to hatred on the basis of “religious belief, sexual orientation, disability, colour, race, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or national origins”. Hopefully an incoming Labour government will address this question. At the very least the Labour leadership should commit to reviewing current legislation, possibly as part of its proposed review of the discredited and counterproductive Prevent strategy.

First published on Medium in June 2017