Not the ‘Cunard Yanks’: The real origins of the Beatles’ R&B covers

The merchant seamen from Merseyside known as “Cunard Yanks” are commonly credited with bringing back from the US the black rhythm & blues recordings that decisively influenced the development of the Beatles’ musical style and provided a large part of the group’s early repertoire.

The merchant seamen from Merseyside known as “Cunard Yanks” are commonly credited with bringing back from the US the black rhythm & blues recordings that decisively influenced the development of the Beatles’ musical style and provided a large part of the group’s early repertoire.

Pop historian Bob Stanley has endorsed this view, writing that it is “widely known that the Cunard liners that did round trips from Liverpool to New York were the financial and inspirational source material for Merseybeat — men working on the ships brought back jukeboxes as well as stacks of unknown records”. This was, he wrote in his encyclopedic study of post-war popular music Yeah Yeah Yeah, “how the kids with guitars in Liverpool were introduced to early soul, R&B and manic rockers that their contemporaries in Lincoln, Luton or Leeds would have struggled to hear”.

In Liverpool itself this story has become an officially recognised part of the city’s cultural history. For example, the 2007 documentary film Liverpool’s Cunard Yanks was tied in to the promotion of Liverpool as European Capital of Culture and premiered at the Philharmonic Hall, while last year it was screened at a Lord Mayor’s Charity event. The film presents the established view of the transatlantic connection in unequivocal terms. Narrator Paul Gambaccini states that the Cunard Yanks “brought back and circulated records never heard before or released in Britain” and were “responsible for a music revolution which influenced the Liverpool Sound and the Beatles”.

But is this really what happened? In his 2015 study The Twenty-First-Century Legacy of the Beatles musicologist Mike Brocken subjects the “Cunard Yanks-into-Merseybeat story” to detailed scrutiny. While he gives space to contrary views, Brocken doesn’t conceal his own scepticism towards the story, which he says originated in the 1970s and was “borne of the early stages of Beatles tourist heritage”. It then became “embedded into local popular music consciousness without what might be described as ‘thick’ historical research taking place”. As for the Liverpool’s Cunard Yanks film, Brocken points out that it identified just one merchant seaman who brought records back from the US in large numbers, and these were mainly jazz albums.

Other experts in the field have been even more forthright in their opposition to the Cunard Yanks narrative. Alan Clayson and Spencer Leigh devoted a chapter of their 2003 book The Walrus Was Ringo: 101 Beatles Myths Debunked to a refutation of the theory. Leigh expanded on this argument in a 2013 article for Record Collector magazine, in which he quoted from an interview with Bob Wooler, who as compère and DJ at the Cavern Club and friend to the Beatles was centrally involved in the rise of Merseybeat. Wooler told Leigh:

Other experts in the field have been even more forthright in their opposition to the Cunard Yanks narrative. Alan Clayson and Spencer Leigh devoted a chapter of their 2003 book The Walrus Was Ringo: 101 Beatles Myths Debunked to a refutation of the theory. Leigh expanded on this argument in a 2013 article for Record Collector magazine, in which he quoted from an interview with Bob Wooler, who as compère and DJ at the Cavern Club and friend to the Beatles was centrally involved in the rise of Merseybeat. Wooler told Leigh:

“I accept that there were hundreds of Cunard Yanks and that, before the War, they brought back dance band records which were unavailable here. In the 1950s they brought back country and western records which were not released here. However, there is no evidence that the beat groups were performing songs brought over from America by the Cunard Yanks.”

Mark Lewisohn’s The Beatles: All These Years — Volume 1 — Tune In, also published in 2013, similarly reported Bob Wooler’s rejection of the Cunard Yanks story, noting that Wooler had been “finger-proddingly emphatic on the point”. Lewisohn concluded that while the Cunard Yanks “have a vital and fascinating history, and played their part in shaping local lives, they had little or none of the influence on the Beatles’ music that commentators have always suggested”.

So, if not from the Cunard Yanks, where did the Beatles acquire the R&B records that served as such an inspiration for them in their formative years? The answer, as founder and editor of Mersey Beat magazine Bill Harry has confirmed, is that they had no need to rely on singles imported from the US via the transatlantic sea link, because the music was available on UK labels and could be bought over the counter (or heard for free in a listening booth if money was short) at Liverpool record stores. To quote Lewisohn, the Beatles “got their American music from shops, not ships”.

As George Harrison pointed out in an interview for the 1995 TV documentary series The Beatles Anthology:

“Because there were a lot of record companies in America, lots of records seemed only to be distributed on a local basis. It was very regional; some were lucky enough to get distributed nationwide and others weren’t. However, many of the small companies were affiliated with major labels that had distribution in the UK, so some obscure American records ended up being sold in the UK but unknown in America. There are some incredible R&B records from America that I find most Americans have never heard of.”

The Beatles had ready access to such records after Brian Epstein became their manager in January 1962, because he was in charge of the record department at the NEMS music store in Liverpool that his family owned. Harrison recounted:

The Beatles had ready access to such records after Brian Epstein became their manager in January 1962, because he was in charge of the record department at the NEMS music store in Liverpool that his family owned. Harrison recounted:

“Brian had had a policy at NEMS of buying at least one copy of every record that was released. If it sold, he’d order another one, or five or whatever. Consequently he had records that weren’t hits in Britain, weren’t even hits in America. Before going to a gig we’d meet in the record store, after it had shut, and we’d search the racks like ferrets to see what new ones were there.

“That’s where we found artists like Arthur Alexander and Ritchie Barrett (‘Some Other Guy’ was a great song), and records like James Ray’s ‘If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody’. These were songs which we used to perform in the clubs in the early days, and which many British bands later started recording. ‘Devil In Her Heart’ and Barrett Strong’s ‘Money’ were records that we’d picked up and played in the shop and thought were interesting.”

Spencer Leigh (who “bought many US R&B records, usually from NEMS, yet never knew a sailor”) has identified around 350 cover versions of US recordings by Liverpool groups. This is what he found: “In almost every case the original version had been released in the UK on such labels as Top Rank, Oriole, London American (for the Decca group), Stateside (EMI) and Pye International.” Let’s check out the Beatles’ cover versions of US R&B records to see if this applies in their case.

Please Please Me

The Beatles’ first album Please Please Me, issued in early 1963, featured five covers of R&B recordings by US black artists. These were “Anna (Go To Him)” by Arthur Alexander, “Chains” by the Cookies, “Boys” and “Baby It’s You” by the Shirelles, and the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout”. As can be seen below, all of these recordings had already been released on UK labels.

They generally didn’t sell very well and so would have been unfamiliar to most pop fans — the one exception being “Boys”, which was the B-side of the 1961 top ten hit “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” (The only other record to have charted at all was “Chains”, which made it to No.50 on the Record Retailer chart for a week in January 1963 before dropping straight out again.) But the point is that these records were available, without any assistance from the Cunard Yanks, to R&B enthusiasts like the Beatles who took the trouble to search them out.

With The Beatles

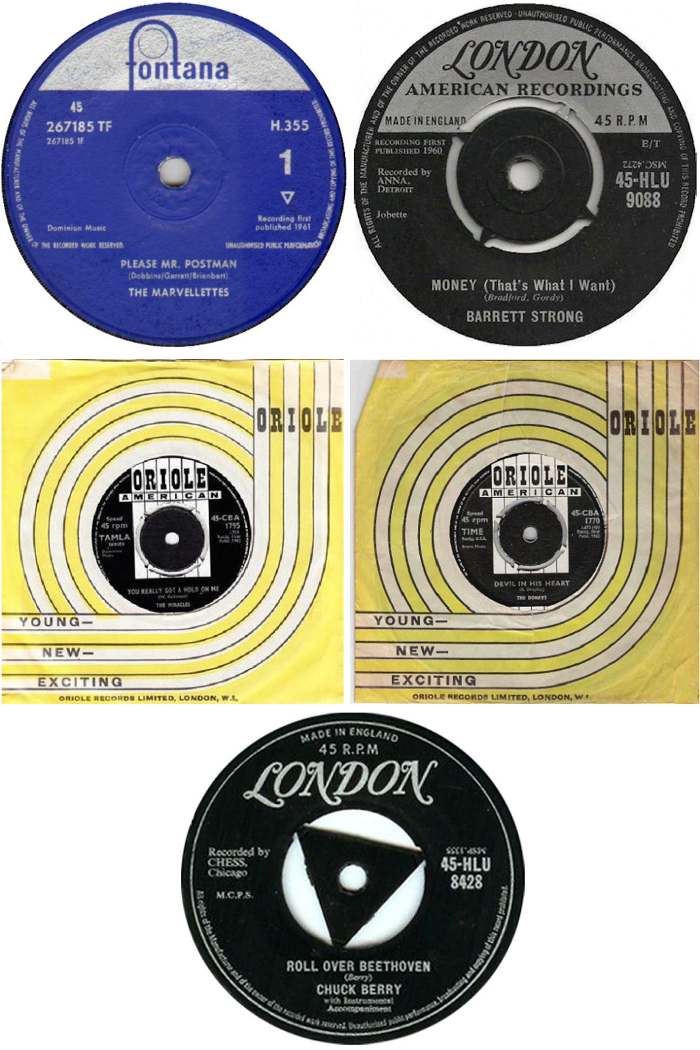

The follow-up album With The Beatles was issued later in 1963 and similarly featured five covers of US R&B records, all of which were available in the UK. They included Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven” and the obscure B-side “Devil In His Heart” by the Donays, a girl group from Detroit. The other three songs — the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr Postman”, the Miracles’ “You Really Got A Hold On Me” and Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want)” — were from Detroit too, all being Motown productions. Although it wasn’t until 1965 that the Tamla Motown label was launched in the UK, Motown recordings were distributed before that on a variety of British labels — London, Oriole, Fontana and Stateside — and this was the case with these three 45s.

Long Tall Sally EP

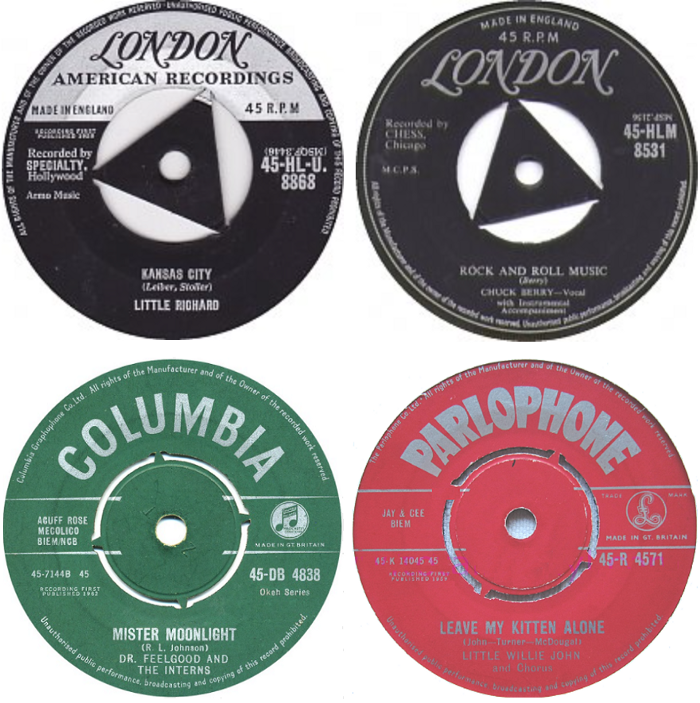

The Beatles’ third album, 1964’s A Hard Day’s Night, was notable for the fact that every song on it was a Lennon-McCartney composition, an unprecedented achievement for a pop group at the time. However, during the sessions for the album the Beatles did cut two R&B covers, of Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” and Larry Williams’ “Slow Down”, both of which appeared on the Beatles EP Long Tall Sally. Again, the originals were recordings that were available in the UK, having been issued on the London label. In fact “Long Tall Sally” had provided little Richard with his biggest UK hit, having reached No.3 in the charts in 1957.

Beatles For Sale

When the group recorded their fourth LP Beatles For Sale later that year they were under pressure to get a record out in time to catch the Christmas market, and due to a gruelling tour schedule were unable to write an album’s worth of new material. So they reverted to the mix of cover versions and original compositions that had characterised their first two albums. The covers were of songs that had been a part of the Beatles’ live sets during the 1961–62 period, according to Mark Lewisohn’s The Complete Beatles Chronicle, and therefore had the advantage of requiring little rehearsal.

These included Chuck Berry’s “Rock And Roll Music”, Little Richard’s “Kansas City”, “Mr Moonlight” by Dr Feelgood and the Interns (aka Piano Red), and Little Willie John’s “Leave My Kitten Alone” — although the cover of the latter was omitted from the album and didn’t receive an official release until it was included in the 1995 compilation Anthology 1. All these records had been issued in the UK, on the London, Columbia labels and Parlophone labels.

“Mr Moonlight” was another obscure B-side, having appeared on the flip of the minor 1962 US hit “Dr Feel-good”, but was evidently popular with beat groups in the UK, having previously been covered by the Merseybeats (as the B-side of their 1963 hit “I Think Of You”) and the Hollies (on their 1964 album Stay With The Hollies). Not everyone shares this enthusiasm for the song, with the Beatles’ version sometimes being dismissed as their worst ever recording. (By people who presumably have never heard “The Sheik Of Araby”.)

“Kansas City” was composed by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller and originally recorded by Little Willie Littlefield in 1952, but it was Little Richard’s very free interpretation of the song that the Beatles copied. (He obviously couldn’t remember the words and improvised some not entirely coherent lyrics of his own.) The Beatles’ recording was later the subject of legal action by Little Richard’s publishers who claimed disingenuously that it incorporated Little Richard’s own copyrighted composition “Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey” (which in fact dates from after his recording of “Kansas City” and was itself a blatant rip-off of the Leiber-Stoller piece). Subsequently the track was retitled “Medley: Kansas City/Hey, Hey, Hey, Hey”, with half of the composers’ royalties going to Little Richard.

Whether the Beatles were inspired by Little Willie John’s version of “Leave My Kitten Alone” is uncertain. In an interview with Mark Lewisohn for The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions Paul McCartney described it as “a Johnny Preston song”, referring to a 1961 cover version by the white American pop singer of that name. This may have been how the Beatles first came across the song. However, given their inclination to search out R&B obscurities, it’s not unlikely that they would have been familiar with the Little Willie John original too, so I have included it here.

Help! sessions

1965’s Help! album was made up predominantly of compositions by Lennon-McCartney and George Harrison, but it did include a cover of Larry Williams’ “Dizzy Miss Lizzy”. This was recorded at the same session as another Williams song, “Bad Boy”, in response to a request by the Beatles’ US label Capitol to provide material for the forthcoming American album Beatles VI. As had been the case with Beatles For Sale, when under pressure to come up with new recordings at short notice the group reached back into their early sixties repertoire (Lewisohn states that both titles featured in Beatles live sets during 1960–62). “Bad Boy” wasn’t issued in the UK until the end of 1966 when it appeared on the compilation A Collection Of Beatles Oldies. Both of the Williams originals were released here on the London label.

That completes the survey of R&B covers from the Beatles’ studio albums and EPs, between 1963 and 1965. Not to labour the point, but every one of the original US records had been issued on UK labels.

Decca audition

Recordings the Beatles made at the Decca studio in January 1962, in an unsuccessful attempt to secure a contract with that label, included material they didn’t re-record after signing with Parlophone later that year. The Decca R&B covers included “Searchin’” and “Three Cool Cats” by the Coasters, and Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee”. These had all been issued on the London label.

(I’m going to ignore “Bésame Mucho”, because although it entered the Beatles’ repertoire via the Coasters’ version, which was released in the UK on the London label, it’s hardly R&B. Also excluded is “The Sheik Of Araby”, which was possibly adapted from Fats Domino’s interpretation — it had appeared on his album …A Lot Of Dominos! — but doesn’t qualify as R&B either. Some might argue it barely qualifies as music.)

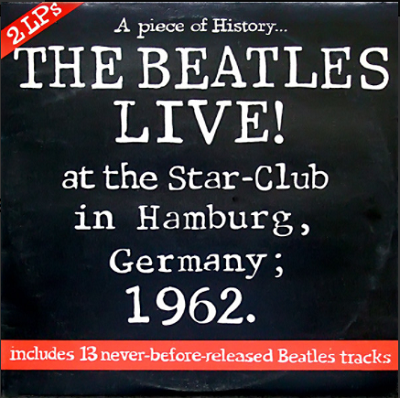

Star-Club, Hamburg

In December 1962 the Beatles travelled to Hamburg for their final dates at the Star-Club, and an unofficial tape of their performances has long been circulated in various forms. Here too we find a number of R&B cover versions that were not recorded for the studio albums or EPs. Again all the originals could be found on UK labels.

They are Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen”, “Little Queenie” and “I’m Talking About You”, Bo Diddley’s “Road Runner”, Arthur Alexander’s “Where Have You Been (All My Life)?” and the Olympics’ “Shimmy Like Kate” (issued in the UK under the song’s original title “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate”).

They are Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen”, “Little Queenie” and “I’m Talking About You”, Bo Diddley’s “Road Runner”, Arthur Alexander’s “Where Have You Been (All My Life)?” and the Olympics’ “Shimmy Like Kate” (issued in the UK under the song’s original title “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate”).

The Beatles also performed “Your Feet’s Too Big”, which was closely identified with the 1939 recording by Fats Waller, of whom McCartney was an admirer. The Star-Club version was almost certainly taken from a track on Chubby Checker’s album For Twisters Only, though, so can be categorised as R&B.

The Star-Club tapes include a rocked-up version of the standard “Red Sails In The Sunset”, which was a UK single for Emile Ford and the Checkmates. But Bob Wooler stated that the Beatles’ cover was derived from Ray Sharpe’s earlier version, which makes sense considering their fondness for obscure B-sides (it was the flip of the better known “Linda Lu”).

(Another song from the set was “Hallelujah I Love Her So”, but this was a cover of Eddie Cochran’s version rather than the Ray Charles R&B original, so I have left it out.)

BBC radio sessions

Further R&B covers recorded for radio broadcasts between 1963 and 1964 can be found on the collections Live At The BBC and On Air — Live At The BBC Volume 2. (I have checked these against the Purple Chick 10-CD bootleg series Complete BBC Sessions which includes a lot more material but no additional R&B numbers, just multiple performances of the same songs.)

The covers taped for the BBC that can’t be found in the recordings cited above were Arthur Alexander’s “A Shot Of Rhythm And Blues” and “Soldier Of Love”, Little Eva’s “Keep Your Hands Off My Baby”, the Coasters’ “Young Blood” and Richie Barrett’s “Some Other Guy”. (The last-named had been a mainstay of the Beatles’ setlist at the Cavern, where Granada TV filmed them performing it in August 1962.) Little Richard’s “Lucille” and “Ooh! My Soul” were featured, while Chuck Berry was represented by “Johnny B. Goode”, “Carol”, “Too Much Monkey Business” and his version of Doctor Clayton’s “I Got To Find My Baby”. (I’ve excluded “I Got A Woman” because it was based on Elvis Presley’s version rather than the Ray Charles original.)

All of these were available as singles on the London label, with the exception of “Too Much Monkey Business” and “I Got To Find My Baby”, neither of which was issued as a 45 in the UK. It wasn’t until the release in 1963 of the Pye International compilation albums Chuck Berry and More Chuck Berry that those recordings became easily accessible to British R&B fans. But Mark Lewisohn’s The Complete Beatles Chronicle states that the group were already performing “Too Much Monkey Business” and “I Got To Find My Baby” in 1960–61. So in the case of these two R&B originals at least, it is unclear where the Beatles acquired them.

Around The Beatles

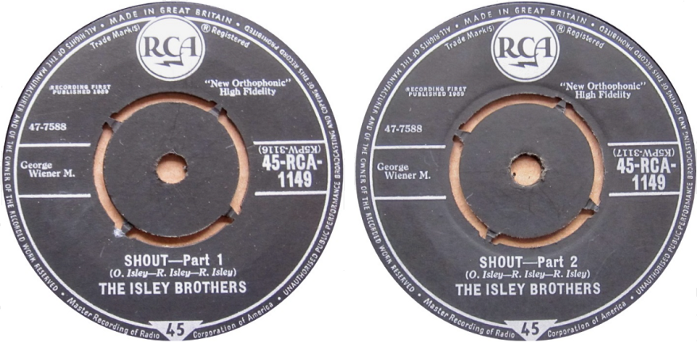

The Anthology 1 compilation includes a number of performances from the May 1964 TV special Around The Beatles, one of which is a cover of the Isley Brothers’ “Shout”. According to The Complete Beatles Chronicle the group featured the song in live concerts in 1960–61, but this is the only extant recording so far as I know. The Isley Brothers original was released in the UK in 1959 on the RCA label.

Live performances

Then there is the question of the R&B numbers that were part of the Beatles’ repertoire over the years but were not recorded, either officially or unofficially. For The Complete Beatles Chronicle Mark Lewisohn compiled a list of all the songs the group performed live, from the Quarry Men days up to when the Beatles ceased touring in 1966, which is of great assistance in identifying these numbers. (I’m not going to post screenshots of all the records in this section, but I’ve identified the UK issues where possible and provided the details.)

Lewisohn warned that his list was “almost certainly incomplete for the years 1957–63”, and in the later study The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul Walter Everett did publish his own lists of numbers from the group’s early repertoire that included a few additional R&B covers. Everett conceded that some of his attributions were speculative, though, so what follows is based mainly on Lewisohn.

Some of these covers are well known. The Beatles remained proud of their discovery of James Ray’s “If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody”, and the fact that Manchester group Freddie and the Dreamers appropriated their song and scored a No.3 hit with an inane travesty of it still rankled with Paul McCartney decades later. The Beatles’ appreciation of Bobby Parker’s “Watch Your Step” is also common knowledge, given that the guitar riff was notoriously lifted for “I Feel Fine”, showing that the Beatles were not averse to a bit of appropriation themselves.

In view of McCartney’s admiration for Little Richard, it’s not surprising that Lewisohn’s list includes many of his songs, all of which were released in the UK on the London label. These are “Rip It Up” and “Ready Teddy” (both on HLO 8336), “Tutti Frutti” (HLO 8366), “Send Me Some Lovin’” (HLO 8446), “Miss Ann” (HLO 8470), “Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave” (HLO 8509) and “Good Golly Miss Molly” (HLU 8560). Since Lewisohn’s book was published a 1960 Beatles setlist has emerged which includes another Little Richard number, “Jenny Jenny” (HLO 8470).

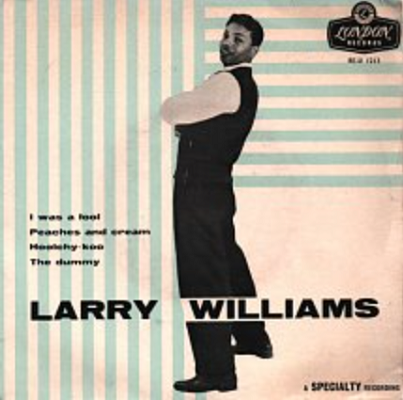

John Lennon for his part was a Larry Williams enthusiast and the Lewisohn list includes Williams’ two UK hits, “Short Fat Fannie” and “Bony Moronie”, both of which were issued here on the London label (HLN 8472 and HLU 8532 respectively). Also covered was the less well known Williams number “Peaches And Cream”, which wasn’t a single in the UK but would have been available to the Beatles as a track on the EP Larry Williams (London REU 1213).

John Lennon for his part was a Larry Williams enthusiast and the Lewisohn list includes Williams’ two UK hits, “Short Fat Fannie” and “Bony Moronie”, both of which were issued here on the London label (HLN 8472 and HLU 8532 respectively). Also covered was the less well known Williams number “Peaches And Cream”, which wasn’t a single in the UK but would have been available to the Beatles as a track on the EP Larry Williams (London REU 1213).

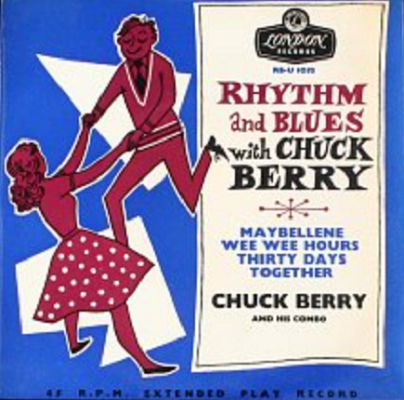

Chuck Berry was also well represented. The Beatles covered his first two US hits, “Maybellene” and “Thirty Days (To Come Back Home)”, which were not released as singles in the UK but did appear on the London label EP Rhythm And Blues With Chuck Berry (REU 1053). Other Berry records on the Lewisohn list, issued as singles on the same label, were “Reelin’ And Rockin’” (HLM 8585), “Vacation Time” (HLM 8677) and “Almost Grown” (HLM 8853).

Chuck Berry was also well represented. The Beatles covered his first two US hits, “Maybellene” and “Thirty Days (To Come Back Home)”, which were not released as singles in the UK but did appear on the London label EP Rhythm And Blues With Chuck Berry (REU 1053). Other Berry records on the Lewisohn list, issued as singles on the same label, were “Reelin’ And Rockin’” (HLM 8585), “Vacation Time” (HLM 8677) and “Almost Grown” (HLM 8853).

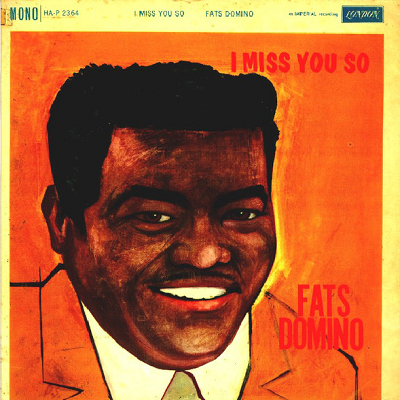

Fats Domino’s work figures prominently on the list, with six entries. Between 1955 and 1961 Fats had twenty records in the UK top 50 (Chuck Berry by comparison had only six) so it’s understandable that the Beatles should perform his material, even if his rather laid-back piano-based New Orleans R&B had little direct influence on their musical style (“Lady Madonna” excepted). The records covered were the London label singles “I Know” (HL 8133), “Ain’t That A Shame” (HLU 8173), “I’m In Love Again” (HLU 8280), “Coquette” (HLP 8759) and “I’m Gonna Be A Wheel Someday” (HLP 8942). The Beatles also performed “I’ll Always Be In Love With You” from the album I Miss You So (London HA-P 2364).

Fats Domino’s work figures prominently on the list, with six entries. Between 1955 and 1961 Fats had twenty records in the UK top 50 (Chuck Berry by comparison had only six) so it’s understandable that the Beatles should perform his material, even if his rather laid-back piano-based New Orleans R&B had little direct influence on their musical style (“Lady Madonna” excepted). The records covered were the London label singles “I Know” (HL 8133), “Ain’t That A Shame” (HLU 8173), “I’m In Love Again” (HLU 8280), “Coquette” (HLP 8759) and “I’m Gonna Be A Wheel Someday” (HLP 8942). The Beatles also performed “I’ll Always Be In Love With You” from the album I Miss You So (London HA-P 2364).

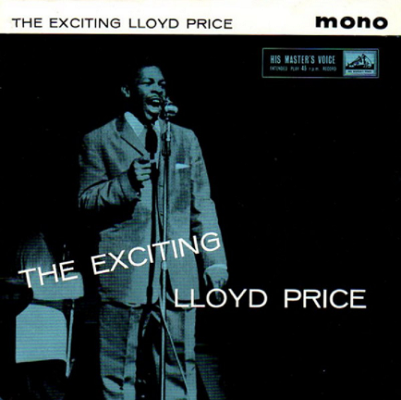

Fats’ distinctive piano playing featured on Lloyd Price’s 1952 US hit “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” which the Beatles also covered along with its B-side “Mailman Blues”, although the single was not released in the UK. The Beatles must initially have come across “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” through Elvis’s cover version, which appeared on his first UK album Elvis Presley Rock ’n’ Roll and was later a hit single. However, the Lloyd Price original would have been available to them on the EP The Exciting Lloyd Price (His Master’s Voice 7EG 8538) which also included “Mailman Blues”.

Fats’ distinctive piano playing featured on Lloyd Price’s 1952 US hit “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” which the Beatles also covered along with its B-side “Mailman Blues”, although the single was not released in the UK. The Beatles must initially have come across “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” through Elvis’s cover version, which appeared on his first UK album Elvis Presley Rock ’n’ Roll and was later a hit single. However, the Lloyd Price original would have been available to them on the EP The Exciting Lloyd Price (His Master’s Voice 7EG 8538) which also included “Mailman Blues”.

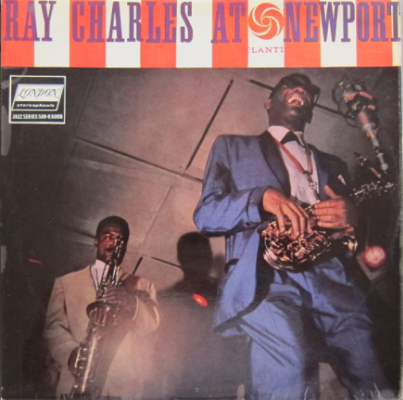

Another source was Ray Charles. Covers of his work predictably included “What’d I Say” (London HLE 8917) which was a favourite of Liverpool groups, one notable recording being by the Big Three on their At The Cavern EP. The Beatles also performed “Don’t Let The Sun Catch You Cryin’” (London HLE 9058), along with “Sticks And Stones” and “Hit The Road Jack” (His Master’s Voice POP 774 and POP 935 respectively). Another Ray Charles number covered was his 1955 US hit “A Fool For You”, although this was not issued as a single in the UK. The Beatles would have taken their version from the live recording on the album Ray Charles At Newport (London SAH-K 6008) or the EP of the same title (London REK 1317).

Another source was Ray Charles. Covers of his work predictably included “What’d I Say” (London HLE 8917) which was a favourite of Liverpool groups, one notable recording being by the Big Three on their At The Cavern EP. The Beatles also performed “Don’t Let The Sun Catch You Cryin’” (London HLE 9058), along with “Sticks And Stones” and “Hit The Road Jack” (His Master’s Voice POP 774 and POP 935 respectively). Another Ray Charles number covered was his 1955 US hit “A Fool For You”, although this was not issued as a single in the UK. The Beatles would have taken their version from the live recording on the album Ray Charles At Newport (London SAH-K 6008) or the EP of the same title (London REK 1317).

As already noted, the Beatles demonstrated their enthusiasm for the Shirelles by recording two covers of their records for the Please Please Me album, and the Lewisohn list includes three more: “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” and “Mama Said” (Top Rank JAR 540 and JAR 567 respectively), and “Love Is A Swingin’ Thing” (His Master’s Voice POP 1019). In a similar girl group vein there was Little Eva’s “The Loco-Motion” (London HL 9581).

As for male vocal groups, the Beatles were big fans of the Coasters, whose “Yakety Yak” (London HLE 8665) and “Thumbin’ A Ride” (London HLK 9293) are included by Lewisohn, while another list supplied by Bob Wooler adds “I’m A Hog For You” (London HLE 8938). The Olympics were represented by “Well!” (His Master’s Voice POP 528) and “(Baby) Hully Gully” (Columbia DB 4346), the Marathons by “Peanut Butter” (Vogue 9185), and Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs by “Stay” (Top Rank JAR 526). The Drifters’ “Save The Last Dance For Me” (London HLK 9201) and “When My Little Girl Is Smiling” (London HLK 9522) were covered, as was their former lead singer Ben E. King’s solo record “Stand By Me” (London HLK 9358).

Bobby Freeman was the origin of several items on the list. His “Do You Wanna Dance” (London HLJ 8644) was one, along with “(I Do The) Shimmy Shimmy” and its flip “You Don’t Understand Me” (Parlophone R 4684). Individual entries were Bo Diddley’s “Crackin’ Up” (HLM 8913), Sam Cooke’s “Bring It On Home To Me” (RCA 1296), Bruce Channel’s “Hey! Baby” (Mercury AMT 1171) and “One Track Mind” by Bobby Lewis (Parlophone R 4831).

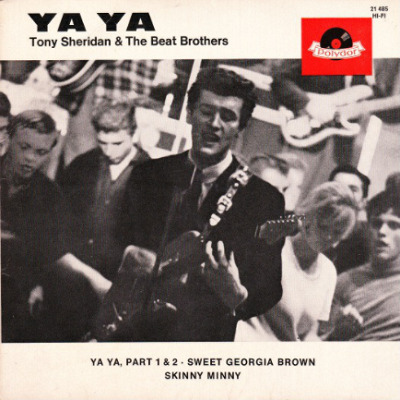

One US R&B number from the Lewisohn list that I couldn’t locate a contemporary UK release for was Lee Dorsey’s 1961 US hit “Ya Ya”, which wasn’t issued here until 1965 when it appeared on the Sue label. Lewisohn states that the Beatles performed this song in the 1961–62 period, and it was certainly familiar to musicians on the early sixties Hamburg scene. Beatles associate Tony Sheridan (of “My Bonnie” fame) recorded “Ya Ya” for a Polydor EP of that name (backed by a group sometimes erroneously identified as the Beatles) which was released in Germany in October 1962. The source was very likely a 1961 German issue of the Dorsey original on the Metronome label (J 45–600).

One US R&B number from the Lewisohn list that I couldn’t locate a contemporary UK release for was Lee Dorsey’s 1961 US hit “Ya Ya”, which wasn’t issued here until 1965 when it appeared on the Sue label. Lewisohn states that the Beatles performed this song in the 1961–62 period, and it was certainly familiar to musicians on the early sixties Hamburg scene. Beatles associate Tony Sheridan (of “My Bonnie” fame) recorded “Ya Ya” for a Polydor EP of that name (backed by a group sometimes erroneously identified as the Beatles) which was released in Germany in October 1962. The source was very likely a 1961 German issue of the Dorsey original on the Metronome label (J 45–600).

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is not to dismiss the broader cultural impact of the Cunard Yanks, for which there exists much anecdotal evidence. Nor is it the intention to deny that some R&B records may have reached Merseyside musicians via the transatlantic sea route. (Ted Taylor of Kingsize Taylor and the Dominoes has insisted that he initially acquired records that way.) What is disputed here is the story that the Cunard Yanks played a central role in introducing into Liverpool the US R&B records that were crucial to the development of Merseybeat as a whole and the musical evolution of the Beatles in particular.

I have documented over ninety US R&B records that the Beatles covered and have identified UK releases for almost all of them, with only a few exceptions (Chuck Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business” and “I Got To Find My Baby”, and Lee Dorsey’s “Ya Ya”). Mark Lewisohn’s statement that “the music the Beatles played, while it came from America, reached them from records licensed by British companies, pressed in Britain and sold in shops like NEMS” turns out to be correct. This may be less romantic than the Cunard Yanks myth, but it does have the merit of historical accuracy.

Sources

The Beatles, The Beatles Anthology (2000)

David Britton, “Kingsize Taylor — no pratt: Liverpool’s original rocker”, Savoy Records (1985)

Michael Brocken, “Some other guys! Some theories about signification: Beatles cover versions”, Popular Music and Society, Vol.20 No.4 (1996)

Michael Brocken, Other Voices: Hidden Histories of Liverpool’s Popular Music Scenes, 1930s-1970s (2010)

Michael Brocken, The Twenty-First-Century Legacy of the Beatles: Liverpool and Popular Music Heritage Tourism (2015)

Alan Clayson and Spencer Leigh, The Walrus Was Ringo: 101 Beatles Myths Debunked (2003)

Nick Duckett, Liner notes for the Beatles Beginnings CD series (2010–2013)

Paul du Noyer, Liverpool — Wondrous Place: From the Cavern to the Capital of Culture (2007)

Walter Everett, The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul (2001)

Bill Harry, The British Invasion: How The Beatles and Other UK Bands Conquered America (2004)

Bill Harry, Bigger Than the Beatles (2009)

David Kmiot, Representations of Liverpool Exceptionalism in the Merseybeat Period, 1960–1965, PhD thesis, University of Liverpool (2019)

Spencer Leigh, “Cavern king”, Record Collector No.227 (July 1998)

Spencer Leigh, “You’ve really got a hold on me”, Record Collector No.411 (February 2013)

Mark Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions (1988)

Mark Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle (1992)

Mark Lewisohn, The Beatles: All These Years — Volume 1 — Tune In (2013)

First published on Medium in November 2020