The ‘Russian drone attack’ on Poland: An overview

A week has passed since the Russian “attack” on Poland on the night of 9–10 September. During that time the details have become clearer, contradicting the narrative that was initially promoted by western politicians and media commentators. So here is my attempt at a summary of what we now know.

You’ll recall that Polish prime minister Donald Tusk originally claimed that Polish airspace had been invaded “a huge number” of Russian drones, some of which had been shot down by Polish air defences or NATO jets because they “posed a direct threat”. Warsaw immediately invoked Article 4 of the NATO treaty, which states that member states should “consult together whenever, in the opinion of any of them, the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the members is threatened”. While this stopped short of triggering Article 5, the famous “collective defense” provision, it was a step in that direction. Tusk himself declared dramatically: “This situation brings us all closer to open conflict, closer than ever since World War II.”

The BBC’s security correspondent Frank Gardner helpfully explained the nature of the threat to Poland: “To be clear, when we talk about drones in this context, these are not the little quadcopters that hunt down soldiers in trenches on the front lines with a grenade or artillery shell slung underneath. These are much larger, pilotless aircraft packed with high explosive. The Iranian-built Shahed-136, for example, measures 3.5m (11 feet) long by 2.5m (8.2 feet) wide. The Russian-made copies of these, the Geran-2, can carry a payload of anywhere between 30–50kg (66–110lb) of explosive, enough to smash into a residential block and kill or maim the inhabitants of several homes.”

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen was among those who jumped in to push this story: “Today, we have seen a reckless and unprecedented violation of Poland and Europe’s airspace by more than 10 Russian Shahed drones. Europe stands in full solidarity with Poland. Europa jest w pełni solidarna z Polską.”

Volodymyr Zelensky agreed: “Today there was another step of escalation — Russian-Iranian ‘shaheds’ operated in the airspace of Poland, in NATO airspace. It was not just one ‘shahed’ that could be called an accident, but at least eight strike drones aimed toward Poland.” Zelensky later claimed, based on a telephone conversation with Tusk, that “debris from Russian drones, including Iranian ‘shaheds’, was found in many towns and villages”. He added: “I offered Poland our assistance, training, and expertise in shooting down Russian drones, particularly ‘shaheds’.”

This version of events quickly fell apart. The official Polish figure for the invading drones was soon reduced from “a huge number” to just 19, only three (or possibly four) of which apparently posed such a direct threat that they were shot down. By the evening of 10 September the wreckage of 16 drones had been recovered, most of them in the Lublin region (the number subsequently rose to 17). Contrary to the scaremongering talk of Shaheds packed with 50kg of high explosive, it turned out that the UAVs were Gerbera decoy drones.

Constructed from plywood and polystyrene foam, these drones imitate Shaheds/Gerans in order to confuse Ukrainian air defences, but can be produced at a fraction of the cost. It is possible to equip them with a small 5kg warhead, but the Lublin prosecutor’s office stated that none of the crashed drones and wreckage they had located included any explosives. This has since been confirmed by deputy prime minister Radoslaw Sikorski.

The use of Gerberas complicates the question of where the drones were launched from. One of those that crashed, evidently because it ran out of fuel rather than as a result of being shot down, was found in a field near the village of Mniszków, which is around 300km from the border with Ukraine. Whereas the Geran-2 has an operational range of 2,500 km, a Gerbera drone’s range is only 600 km as estimated by Ukrainian intelligence, or “below 700 km” according to Russia’s foreign ministry. On those figures, it would not be feasible for a Gerbera drone to have penetrated that far into Poland from anywhere on Russian territory (leaving aside Kaliningrad, and I don’t think anyone is claiming the drones came from there).

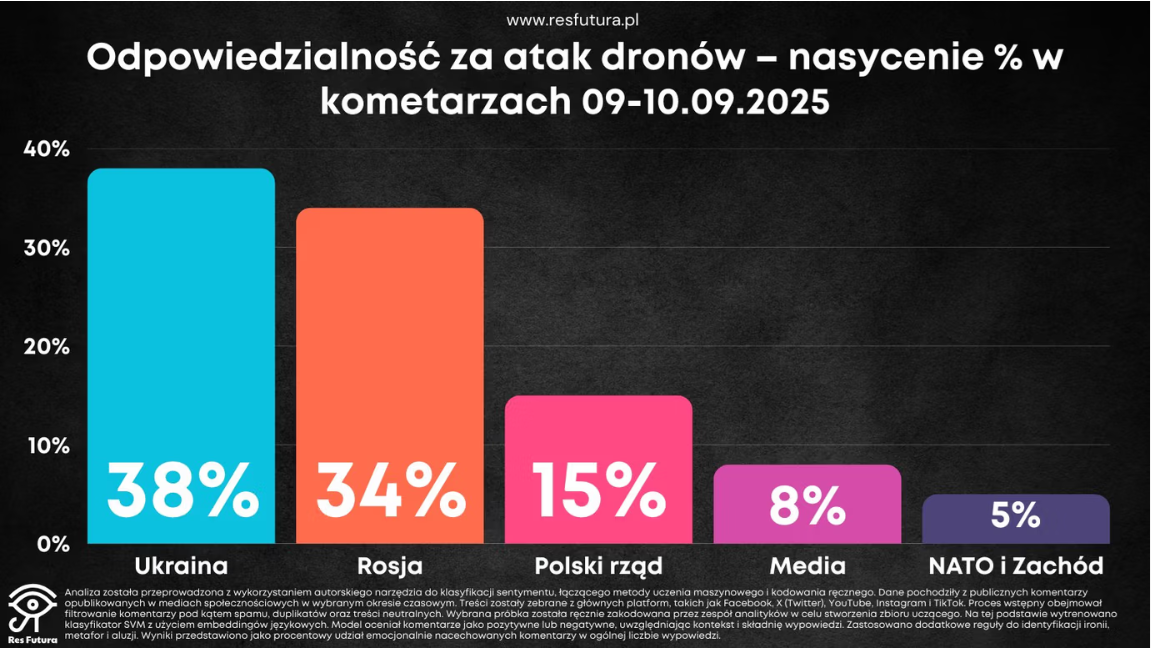

That led to speculation that this was a false flag operation carried out by the Ukrainian military, who repurposed Russian drones they had recovered intact, and sent them across the Polish border in order to stage a provocation against NATO that could be pinned on Moscow. The aim being to draw Poland and other NATO countries directly into the war with Russia. Interestingly, this story was widely accepted in Poland itself according to a Res Futura survey, which attributed the reaction to a Russian disinformation campaign. While a false flag operation is not impossible, as things stand it’s no more than a conspiracy theory lacking any supporting evidence.

However, the Gerbera drones retrieved in Poland apparently had an additional fuel tank fitted into their nose cones. It has been argued that this feature, together with other modifications, could have increased their range to 800–900 km. A drone from the Shatalovo air base in Smolensk oblast — identified by Ukrainian open source intelligence project Dnipro Osint as a launch point — could conceivably have reached Mniszków, which is 895 km away. (Reports that drone debris had been found at Olesno in southern Poland, over a thousand kilometres from Shatalovo, were mistaken. The actual site was the village of Oleśno near Elbląg in northern Poland.)

Poland’s official position, though, was that the UAVs weren’t necessarily launched from inside Russia. Addressing the Polish parliament Tusk stated that “a significant proportion” of them “came directly from Belarus”. Given that Belarus is such a close ally of Russia — their armed forces are just completing the latest of their four-yearly Zapad joint military exercises — it is possible that the Lukashenko government did allow Moscow to launch drones from Belarusian territory. (This would of course have made it rather easier for that Gerbera drone to reach Mniszków.)

But Tusk’s accusation was contradicted by a statement made by the head of the Belarusian armed forces, Major General Pavel Muraveiko, on the morning of 10 September. He reported that the drones had entered his country’s airspace during the previous night and some of them had been destroyed by Belarusian air defences. He didn’t identify the drones’ origin, saying only that the incursion took place during an “exchange of strikes by UAVs between the Russian Federation and Ukraine”. According to Muraveiko, the drones encroached on Belarusian airspace accidentally after they “lost their track as a result of the impact of the parties’ electronic warfare assets”. He claimed that his forces had warned their Polish counterparts that drones were flying towards them across Belarusian territory, giving Poland time to take defensive measures.

In an interview with the news channel TVN24 the head of the Polish armed forces, General Wiesław Kukuła, confirmed that “the Belarusians warned us that drones were heading our way through their airspace” and that “this advance warning was helpful to us”. On the face of it, this does rather undermine the theory that the launch sites were situated in Belarus.

I suppose it could be argued that Aleksandr Lukashenko gave Moscow permission to use his country’s territory to send drones into Poland and then, in order to cover his tracks and avoid a confrontation with NATO, immediately alerted Poland that the drones were on their way, while inventing a story about out-of-control UAVs veering off course through Belarusian airspace. Such a scenario can’t be automatically ruled out, but again it’s just an evidence-free conspiracy theory.

In reaction to Belarusia’s statement, Sikorski insisted that the drones “did not veer off course but were deliberately targeted”. He conceded that “Russian drones have veered into Polish airspace before”, but added: “When one or two drones does it, it is possible that it was a technical malfunction, but as I told you, in this case, there were 19 breaches, and it simply defies imagination that could be accidental.” Donald Trump’s suggestion that the incursion “could have been a mistake” met with a similarly forceful rejection. Tusk tweeted: “We would also wish that the drone attack on Poland was a mistake. But it wasn’t. And we know it.”

A judgement on whether electronic warfare could in fact have accidentally misdirected such a large number of drones into Polish airspace requires a lot more knowledge of military technology than I have. (One expert argues that it could.) But I think it’s highly unlikely that either Tusk or Sikorski really wish that the drone incursion was a mistake. They represent a hawkishly anti-Russian tendency in Polish politics — certainly by comparison with president Karol Nawrocki — and the crisis presented them with an opportunity to hype up the Russian menace to Europe and advocate a more aggressive military policy.

In an interview with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Sikorski was asked about calls by Zelensky’s chief of staff Andriy Yermak for NATO to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine. He replied that the protection of Poland’s population “would of course be greater if we could combat drones and other flying objects beyond our national territory. If Ukraine were to ask us to shoot them down over its territory, that would be beneficial for us. If you ask me personally: We should consider it.” As Dmitry Medvedev of Russia’s security council pointed out in response, the adoption of such a policy would “mean only one thing — a war between NATO and Russia”.

This brings us to the question of the Russian government’s motives for such an attack. What could it hope to gain? The typical answer is that it was testing NATO’s air defences and combat readiness. Speaking to the Guardian, Sikorski cited the fact that the drones were not carrying explosives as evidence that “Russia tried to test us without starting a war”. That is a possibility. The problem with this explanation, though, is that while the Russian military no doubt gained some useful information about the defensive capabilities of Poland and its NATO allies, the latter were obviously going to be alerted to any weaknesses exposed by the attack and would take measures to rectify them. NATO is now upgrading Poland’s air defences, with France, Germany, Denmark and the UK contributing fighter jets and other military assets. It is difficult to see how this entirely predictable response to the drone incursion is to Russia’s benefit.

More generally, the drone crisis has greatly assisted European governments in their efforts to rally public support behind a planned increase in military expenditure to 5% of GDP. The challenge they face is that their electorates may revolt against guns-not-butter budgets that cut back on social spending while hiking the share of national income committed to armaments. This choice of priorities has to be justified by painting a misleading picture of Vladimir Putin pursuing a violent expansionist policy aimed at restoring the borders of the Soviet Union or the Tsarist empire, or even conquering the whole of Europe.

So we have been treated to NATO general secretary Mark Rutte’s absurd warning that if Keir Starmer did not massively ramp up defence spending, then the British people had “better learn to speak Russian”. This was followed by the UK goverment’s policy paper National Security Strategy 2025: Security for the British People in a Dangerous World, which featured a foreword by Starmer claiming that “Russian aggression menaces our continent”. It resulted in headlines such as “Brits must ‘actively prepare’ for war on UK soil, chilling government strategy warns”. As you would expect, the drone incident has been used to reinforce this hysterical “when the Russian tanks roll westward” propaganda. What interest would Moscow have in encouraging that?

In short we are faced with three alternatives. Either the drones were launched from Russian and/or Belarusian territory with the intention of testing NATO’s defences. Or the drones were aimed at Ukraine but were driven off course by electronic warfare and entered Polish airspace by accident. Or it was a false flag operation conducted by Kiev in order to frame Russia for an attack on a NATO member state. Which one is true? I honestly don’t know, although an ingrained aversion to conspiracy theories inclines me to reject the third alternative. Forced to choose, I’d probably go for the accidental incursion theory. On balance, this seems rather more likely than the drones being intentionally directed into Poland by Russia. As I say, any advantages Moscow might have gained from that are considerably outweighed by the disadvantages.

Postscript

One of the highly publicised results of the 9–10 September drone incursion was the severe damage caused to a house in the Polish village of Wyryki-Wola. On 12 September, in his speech to the UN Security Council, Poland’s secretary of state Martin Botaski brandished a photo of the wrecked house as evidence that Russia had “tried to target Polish homes”.

This always seemed like nonsense, given that an unarmed lightweight drone of the type that entered Polish airspace couldn’t possibly have caused that much damage, even if it had been aimed at the house and scored a direct hit. Sure enough, it has since been confirmed that the building was probably struck by a missile fired from a Polish F-16 fighter jet whose guidance system malfunctioned.

But the authorities, at regional and national level, attempted to cover this up and make out that the building was hit by a drone, or by debris from a drone. When journalists from the Polish daily Rzeczpospolita challenged the official narrative, Tusk and Sikorski accused them of being Russian stooges and of attacking the reputation of the armed forces.

Postscript 2

CNN published a useful report confirming that the evidence surrounding the drone incursion is contradictory and inconclusive. It states: “US and Western intelligence officials have been unable to determine whether the incursion was accidental or an intentional effort by Russia to probe Western air defenses and gauge NATO’s response.”

After interviewing a dozen senior US and Western military, intelligence, diplomatic and congressional officials, CNN said it became clear that there is “no consensus view across the NATO alliance”. However:

“Privately, some officials have formed an opinion. The senior Western intelligence official told CNN that they were ‘leaning’ towards an assessment that the incident was unintentional, even as they condemned it as a worrying sign that the Kremlin has become more reckless. The US source familiar with the intelligence agreed.”

The article then continues: “Yet, another US military official and one congressional official familiar with the intelligence said it appeared intentional.”

The report also cites the views of “outside analysts”, as in this passage: “And the sheer number of drones that veered into Poland is hardly dispositive, senior officials and outside analysts said, because the drones are often programmed in bulk and in attacks of this size, it’s logical that 19 or 20 might encounter Ukrainian electronic war defenses and respond identically.”

At the least, this calls into question the dogmatic insistence of Tusk and Sikorski that the drones couldn’t possibly have entered Polish airspace by accident and that the incursion must have been a deliberate provocation on the part of Russia.

In light of this, why should we unquestioningly accept the official line from the Polish government, and other warmongering elements within the NATO alliance, that the drone incursion was intentional?