Who funded Keir Starmer’s campaign?

During his successful campaign to succeed Jeremy Corbyn as Labour Party leader, Keir Starmer was repeatedly challenged to reveal the sources of his campaign funding, to no effect.

Although both Rebecca Long-Bailey and Lisa Nandy released lists of their major donors in the course of the campaign, Keir adamantly refused to release his. Despite being vigorously questioned on the issue in a television interview with Andrew Neil on 4 March, he insisted that all his large donations had been declared via the register of MPs’ financial interests, in compliance with parliamentary rules, and that the largest sum he had received was £100,000 from Bob Latham, a fellow lawyer and longtime Labour member in Keir’s constituency of Holborn & St Pancras.

However, as Long-Bailey supporter Jon Trickett pointed out: “By only publishing donations via the register, candidates can self-finance in order to delay accepting donations, allowing them to publish these later on. You don’t have to officially accept a donation for 30 days and then you don’t have to declare it for another 28 days, so it can be 58 days until it’s declared on the register, which will be after the leadership election is over.”

As for the Labour Party’s own rules, they were even less demanding than parliament’s. The candidate code of conduct for the election required only that all donations over £500 should be submitted to the party’s governance and legal unit no later than 60 days after the result of the election was announced. So Keir was under no obligation to provide any of this information to the Labour Party until early in June.

The code of conduct also placed only limited restrictions on the amount of money that a candidate could spend on their campaign. A cap on cash expenditure, resources and donations in kind was set at £1 per Labour Party member and 50p per affiliated or registered supporter. This alone permitted candidates to accept financial support of well over half-a-million pounds from political sympathisers. Moreover, the cap didn’t apply to staffing or office costs. So the potential amount of money that a candidate could spend on their leadership bid was quite eye-watering.

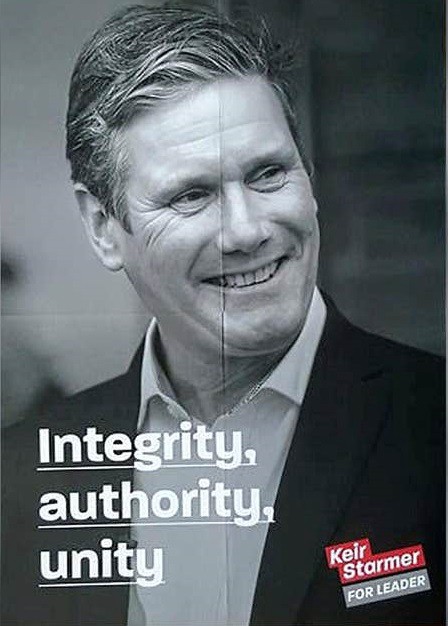

It became clear very early on that Keir Starmer’s campaign was extremely well funded. This attracted attention in February when Keir mailed a fold-out campaign poster to every Labour Party member.

It became clear very early on that Keir Starmer’s campaign was extremely well funded. This attracted attention in February when Keir mailed a fold-out campaign poster to every Labour Party member.

As Rebecca Long-Bailey’s communications director Matt Zarb-Cousin argued, the list of donations Keir had published on the parliamentary website at that point couldn’t possibly have covered the money he was spending. “That all-member mailshot alone would have cost their campaign in the region of £300k”, Zarb-Cousin tweeted. “That’s the basis of questions about funding, the campaign appears to have spent a potentially unprecedented amount.”

With rival candidates having published details of their donations, Keir’s refusal to come clean about the financing of his own campaign made him appear shifty and untrustworthy. I remember Sienna Rodgers of LabourList suggesting that this was a mistake Keir had made due to his training as a lawyer, which led him to adopt a purely legalistic approach to declaring his campaign funding, without taking into consideration the political impact. I found that explanation unconvincing.

Keir was hardly unaware of the damage to his political reputation caused by the failure to reveal his financial backers. It was obvious that he and his advisers must have discussed the problem and decided that the damage that would result from admitting who his financial backers actually were would be even worse. The reasonable assumption was that the identity of these donors was a potential source of severe political embarrassment to Keir.

Keir’s difficulty was that he was appealing for Labour Party members’ votes on the basis of assurances that he would uphold the progressive policies adopted by Labour under Corbyn’s leadership, as embodied in the 10 pledges that appeared on back of the campaign poster. If he wanted to win the election he had little alternative to doing this, given the membership’s overwhelming support for the continuation of the party’s leftwing programme.

If it had got out that Keir’s campaign was being bankrolled by rightwingers with a history of vehement opposition to that progressive programme, his credibility could have been seriously undermined. Members might have concluded that the radical image Keir was projecting was just an opportunist manoeuvre to secure their votes, and that once elected he would steer the party firmly back towards the right.

The latest update to the register of MPs’ financial interests, from 14 April, confirms suspicions about the political character of Keir’s major donors. Here are some of the individuals we now know were significant contributors to his campaign.

Heading the list is media entrepreneur Waheed Alli, who matched Bob Latham’s generosity with a donation of £100,000. Politically close to Tony Blair, who elevated him to the peerage in 1998, Lord Alli gave financial backing to both Liz Kendall and Andy Burnham in the 2015 Labour leadership contest. In 2016 when Angela Eagle put herself forward as a potential leadership challenger to Corbyn, Alli donated £3,000 to her cause.

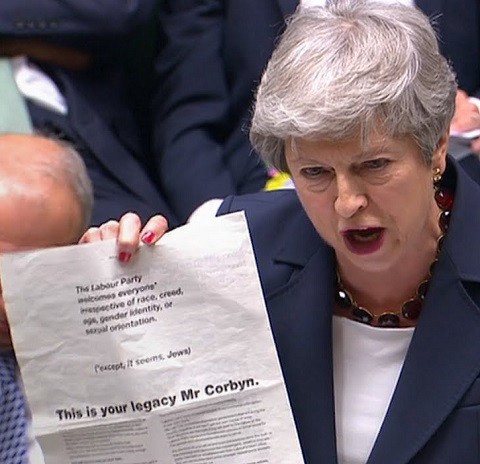

In July last year, in the immediate aftermath of John Ware’s notorious Panorama documentary, from which they took their inspiration, Waheed Alli was one of 64 Labour peers who signed a vitriolic full-page advert in the Guardian denouncing Jeremy Corbyn for “allowing antisemitism to grow in our party and presiding over the most shaming period in Labour’s history”. A Labour spokesperson condemned the advert as containing “false and misleading claims about the party by those hostile to Jeremy Corbyn’s politics”.

In July last year, in the immediate aftermath of John Ware’s notorious Panorama documentary, from which they took their inspiration, Waheed Alli was one of 64 Labour peers who signed a vitriolic full-page advert in the Guardian denouncing Jeremy Corbyn for “allowing antisemitism to grow in our party and presiding over the most shaming period in Labour’s history”. A Labour spokesperson condemned the advert as containing “false and misleading claims about the party by those hostile to Jeremy Corbyn’s politics”.

Needless to say, the attack on Corbyn by Alli and his fellow peers was eagerly seized on by Labour’s enemies, with Theresa May brandishing the advert in the House of Commons during PMQs and triumphantly quoting its disgraceful accusations against Corbyn.

Another generous supporter of Keir’s campaign was Martin Taylor, who contributed £95,000. He was the hedge fund manager who hit the headlines back in March 2015 after it was revealed that he had donated almost £600,000 to Labour over the previous three years. Following Jeremy Corbyn’s election to the leadership in September 2015, Taylor began funding anti-Corbyn groups like Labour Together, Saving Labour and Labour Tomorrow, as well as Dan Jarvis, who was being touted by the Labour right at one point as a possible replacement for Corbyn.

Clive Hollick gave £50,000. Another businessman politically close to Blair, he was a co-founder of the think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research which became closely associated with the New Labour project. In the 2015 Labour leadership contest Lord Hollick gave financial backing to Liz Kendall and in 2016 to Owen Smith.

As it became clear that Smith was going down to a heavy defeat, a frustrated Hollick made no secret of his contempt for Jeremy Corbyn, tweeting that Corbyn was “quite hopeless” and asserting that there was “not a chance under Corbyn” of Labour achieving the 42% of the vote necessary to win a general election.

As it became clear that Smith was going down to a heavy defeat, a frustrated Hollick made no secret of his contempt for Jeremy Corbyn, tweeting that Corbyn was “quite hopeless” and asserting that there was “not a chance under Corbyn” of Labour achieving the 42% of the vote necessary to win a general election.

After Corbyn’s emphatic victory in the leadership election was declared, Hollick recommended to his Twitter followers a scurrilous speech by rightwing Labour MP Tristram Hunt, who claimed that the party was being “held hostage by a far left faction” and accused Corbyn of heading an “irrational leadership cult”.

Trevor Chinn, another former Blair supporter, gave £50,000. Between 2015 and 2019 Chinn donated a total of £60,000 to Tom Watson, who used his position as deputy leader to undermine Corbyn at every opportunity. In 2016 Chinn began donating to Dan Jarvis, presumably in anticipation of Jarvis mounting a challenge Corbyn, before flushing £25,000 down the drain in support of Owen Smith’s leadership bid. Other recipients of Chinn’s largesse have included Liam Byrne, Rachel Reeves, Ian Austin, Ruth Smeeth, Ivan Lewis, Tristram Hunt and the Liberal Democrats. Like Martin Taylor, Chinn has given financial support to Labour Together (£35,000 during 2017–18).

A dedicated pro-Israel lobbyist throughout his life, and therefore a resolute opponent of the pro-Palestinian politics of Jeremy Corbyn, Chinn is an executive committee member of BICOM, which has promoted the view that the Labour Party under Corbyn became riddled with “antisemitic anti-Zionism”. The director of BICOM’s campaign wing, We Believe in Israel, is the well-known anti-Corbyn Labour rightwinger Luke Akehurst.

A dedicated pro-Israel lobbyist throughout his life, and therefore a resolute opponent of the pro-Palestinian politics of Jeremy Corbyn, Chinn is an executive committee member of BICOM, which has promoted the view that the Labour Party under Corbyn became riddled with “antisemitic anti-Zionism”. The director of BICOM’s campaign wing, We Believe in Israel, is the well-known anti-Corbyn Labour rightwinger Luke Akehurst.

We also find that Bet365 owner Peter Coates donated £25,000. Another enthusiastic Labour supporter during the Blair years, Coates told Reuters in 2016 that he would not longer finance a Corbyn-led Labour Party and had “instead made direct personal donations to fund the work of a local Labour parliamentarian, whose centrist views are more aligned to his own”. The parliamentarian in question being Tristram Hunt, who got £40,000 off Coates.

Keir received £25,000 from Martin Clarke. This is presumably the former AA finance director noted for his vehement opposition to Jeremy Corbyn. During the 2015 leadership contest Clarke declared that a victory for Corbyn would be “disastrous”. He stated that he “would be looking at a party which was simply so alien to my own views of what a Labour party is all about” that he “would certainly cease giving money to the party”. Clarke backed Yvette Cooper’s leadership campaign to the tune of £37,500 and later donated £10,000 to the rightwing Labour pressure group Progress.

In April last year Clarke announced that he had resigned from his job with the AA in order to devote his time to building the now defunct “centrist” party The Independent Group/Change UK. It was one of those rare cases of a rat joining a sinking ship.

Keir also received £10,000 from Paul Myners, who served as City Minister in Gordon Brown’s government, although he has never been a Labour Party member himself. Along with Martin Taylor, Lord Myners helped finance the anti-Corbyn group Labour Tomorrow, and like Martin Clarke he threw his weight behind The Independent Group/Change UK, having by his own account provided “a significant amount of money” to help launch it. Myners explained: “I like the idea of a party which brings together people like Chris Leslie and Chuka Umunna from the Labour Party and Heidi Allen and Anna Soubry and the wonderful Dr Wollaston from Totnes from the Conservatives into a single group.”

You’ll note that the total donations from these eight wealthy individual supporters came to an astonishing £455,000. The financial backing Keir received from the organised labour movement paled into insignificance by comparison. UNISON contributed £31,400, while the rightwing unions Community and USDAW each donated £25,000, which came to a total of £81,400. By contrast, Rebecca Long-Bailey received £218,500 in donations from Unite and £52,700 from the CWU, which came to a total of £271,200. Her other major source of financial backing was Momentum. No wealthy businessmen rallied to her campaign.

It was also significant that Rebecca accepted all her donations as soon as they were received, whereas in the case of Keir’s major donations there was almost a month’s gap between receiving and accepting the money. For example, the £100,000 donation from Waheed Alli is listed as received on 24 February but was only accepted on 23 March and wasn’t registered until 9 April, before finally being published on 14 April. By which time, of course, the leadership election was long over and the information could have no effect on the result.

It is obvious that Keir and his advisers exploited parliamentary rules so that Labour Party members were prevented from knowing that his campaign was largely bankrolled by multi-millionaires with a history of opposing Corbyn from the right, and in some cases of backing political parties that stood against Labour.

With hardline anti-Corbyn MPs like Jess Phillips and Liz Kendall now appointed to front bench posts, and Corbyn supporters like Richard Burgon and Dawn Butler relegated to the back benches, those party members who voted for Keir on the basis of his assurances that he would continue Labour’s radical political trajectory might ask themselves whether they were well and truly suckered.

First published on Medium in April 2020