Did Martin Luther King believe criticising Zionists is antisemitic?

Over the years, Martin Luther King Jr’s sympathetic view of Israel has been enthusiastically exploited by Zionists. If you want to defend a racist state based on the dispossession and continued systematic oppression of the Palestinian people, it is obviously helpful to be able to cite the support of a noted anti-racist. Indeed, at one point pro-Israel propagandists thought they had struck gold with the publication in 1999 of Marc Schneier’s Shared Dreams: Martin Luther King, Jr and the Jewish Community, which quoted extensively from a “Letter to an Anti-Zionist Friend” supposedly written by King. The letter included the following passage:

“You declare, my friend, that you do not hate the Jews, you are merely ‘anti-Zionist.’ And I say, let the truth ring forth from the high mountain tops, let it echo through the valleys of God’s green earth: When people criticize Zionism, they mean Jews — this is God’s own truth. Antisemitism, the hatred of the Jewish people, has been and remains a blot on the soul of mankind. In this we are in full agreement. So know also this: anti-Zionist is inherently antisemitic, and ever will be so.”

For the Israel lobby, this emphatic endorsement by King of the bogus “anti-Zionism=antisemitism” argument must have seemed too good to be true. Unfortunately for them, it was. The “Letter to an Anti-Zionist Friend” was long ago exposed as a hoax, although it continues to be quoted on occasion by Zionists. The fall-back position adopted by its former advocates, however, is that while the letter may technically be a forgery, this is of no great significance because it nevertheless represents King’s actual views on Israel. They point in particular to the words attributed to King by the Harvard sociology professor Seymour Martin Lipset (“When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews”), which appear in the image macro at the top of this article. Here is Lipset’s account of how King came to make that alleged statement:

“Shortly before he was assassinated, Martin Luther King, Jr. was in Boston on a fund-raising mission, and I had the good fortune to attend a dinner which was given for him in Cambridge. This was an experience which was at once fascinating and moving: one witnessed Dr. King in action in a way one never got to see in public. He wanted to find what the Negro students at Harvard and other parts of the Boston area were thinking about various issues, and he very subtly cross-examined them for well over an hour-and-a-half. He asked questions, and said very little himself. One of the young men present happened to make some remark against the Zionists. Dr. King snapped at him and said, ‘Don’t talk like that! When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking anti-Semitism!'”

Lipset, it must be said, was hardly a neutral witness. Having been a follower of Max Shachtman during his radical youth, he had broken with Trotskyism in the early 1940s to embrace social democracy, before moving over to the right wing of the Democratic Party and becoming, as the New York Times put it in his obituary, “one of the first intellectuals to be called a neoconservative”. As he abandoned socialism and shifted rightwards, Lipset also became a firm supporter of the state of Israel. “Starting with the Six Day War in 1967”, he later recalled, “I became very active in campus-related Jewish groups.”

All the same, Lipset’s report that he attended a dinner with King is undoubtedly correct. As Martin Kramer has convincingly established, citing contemporary correspondence from the King Center archives, the event took place in October 1967 at the Cambridge, Massachusetts home of future New Republic owner/editor Marty Peretz and his wife Anne, who as the wealthy heiress to the Singer Sewing Machine Company fortune had been a generous donor to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the civil rights organisation of which King was co-founder.

The context to the dinner, as Kramer points out, was the emergence of militantly pro-Palestinian, anti-Zionist sentiments among younger black activists in reaction to the Six Day War of June 1967. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s newsletter had featured a centre spread on “The Palestine Problem”, which expressed forceful opposition to Israel as an imperialist-backed state originating in ethnic cleansing (it cited the role of the “terror gangs” of the Irgun and Lehi) but undermined its case with allegations about the sinister role of Jewish bankers. Marty Peretz, who like Lipset was strongly pro-Israel, had denounced the SNCC article for its “vicious anti-Semitism”. This was followed by the Chicago convention of the National Conference for New Politics, which Peretz was centrally involved in organising, where the Black Caucus provoked a furore by presenting a motion that called for condemnation of the “imperialist Zionist war”. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference later issued a statement rejecting this as “simplistic” and emphasising the role played by their members in getting the motion amended.

When Marty Peretz referred in his invitation letter to King to the need for “some honest and tough and friendly dialogue” about developments over “recent months”, this was no doubt what he had in mind. The large presence of African-American students among the guests suggests that one purpose of the Peretzes’ dinner was to bring King’s moderating influence to bear on those who might be influenced by the SNCC/Black Caucus line on Israel.

So there is no dispute that the dinner took place, or that the Arab-Israeli conflict would likely have played a prominent part in the discussion. What is questionable, though, is the reliability or for that matter the meaning of Lipset’s quotation from King (“When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews”).

Kramer claimed that Lipset “preserved King’s words … by publishing them soon after they were spoken”. But Lipset’s account was in fact published over two years later, in the December 1969 issue of the CIA-funded magazine Encounter. (In the US the article, titled “‘The Socialism of Fools’: The Left, the Jews and Israel”, was also published as a pamphlet by the Anti-Defamation League, who have become notorious for conflating opposition to Israel with antisemitism.) While Lipset probably recalled the general thrust of King’s remarks accurately enough, unless he took shorthand notes it is far from certain that he was able to provide a verbatim quote.

Questioning whether Lipset had memorised the precise wording of King’s intervention doesn’t commit us to the view that he fabricated the story of an argument between King and an African-American student in which King rebuked the student for his attack on Zionists. This incident almost certainly took place. The problem is that Lipset’s version of King’s response is open to the interpretation that King went further than just countering the arguments of one pro-Palestinian student, or indeed of the SNCC and Black Caucus — he appeared to be asserting that any criticism of Zionists is automatically antisemitic. Which of course is why the quotation is so popular with Zionists. But does that reflect King’s actual position?

It is true that King did express his admiration for the state of Israel. Speaking at the annual convention of the Rabbinical Assembly shortly before his murder, he described Israel as “one of the great outposts of democracy in the world, and a marvelous example of what can be done, how desert land can be transformed into an oasis of brotherhood and democracy”. While this may seem naive today, such illusions were not uncommon in progressive circles at the time, at least among the older generation. Whether King would have maintained this rosy view of Israel in the face of subsequent developments we shall never know. In any case, and this is the relevant point here, King’s sympathy for the Zionist project was far from uncritical.

On the eve of the Six Day War, King put his name to a statement that was published as an advert in the New York Times. It warned that the Middle East was “on the brink of war”, blamed the Arab world for the escalation of tensions, and called on the people and government of the US to “support the independence, integrity and freedom of Israel”. However, as Murray Friedman recounts in his 1994 book What Went Wrong? The Creation & Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance, in subsequent discussions with his advisers, as recorded by FBI wiretaps, King “admitted to being confused. He had never actually seen the ad before it appeared, he told them. When he did, he was not happy with it. He felt it was unbalanced and pro-Israel”. King expressed particular concern over a news report in the NYT that had described the statement as a “total endorsement” of Israel. That clearly was not a position he held.

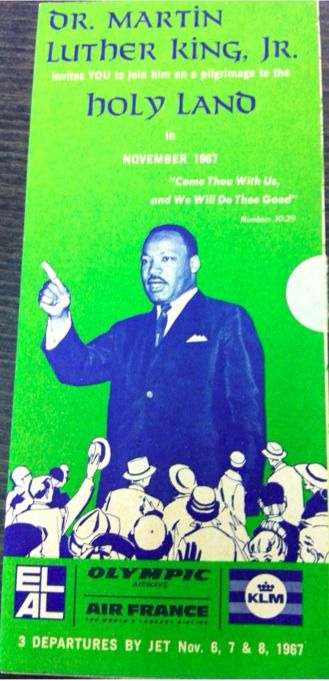

Friedman goes on to note, and Martin Kramer himself has added further details, that as a result of the Six Day War, King cancelled a planned speaking tour of Israel. He did this despite preparations being well advanced, with his impending “pilgrimage to the Holy Land” having been announced at a press conference and some six hundred people having paid their deposits to accompany King on his visit.

Friedman goes on to note, and Martin Kramer himself has added further details, that as a result of the Six Day War, King cancelled a planned speaking tour of Israel. He did this despite preparations being well advanced, with his impending “pilgrimage to the Holy Land” having been announced at a press conference and some six hundred people having paid their deposits to accompany King on his visit.

King justified the decision to cancel on the basis that he didn’t want to be seen as offering public support for Israel’s policies in the immediate aftermath of a war against its Arab neighbours. In a discussion with his advisers (again we have the details courtesy of the FBI’s wiretaps) King stated: “I just think that if I go, the Arab world, and of course Africa and Asia for that matter, would interpret this as endorsing everything that Israel has done, and I do have questions of doubt.” He added: “Most of it would be Jerusalem and they have annexed Jerusalem, and any way you say it they don’t plan to give it up.” Under those circumstances, King argued, to continue with the proposed Israel visit “would be a great mistake”.

This was in July 1967, just three months before King attended the dinner at the Peretzes’ house. Do those sound the words of a man who believed that any criticism of Zionists is by definition antisemitic?

To be fair to Martin Kramer, it should be added that he has modified, or at least expanded on, his earlier assessment of the “When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews” quote. In a revised version of his article on King’s intervention at the Peretzes’ dinner, which forms part of a chapter in his book The War on Error: Israel, Islam, and the Middle East, Kramer offers the following more balanced assessment:

“There is plenty of room to debate the precise meaning of King’s off-the-record words at the Cambridge dinner. Was he only referring to the clearly antisemitic meaning of ‘Zionists’ in the rhetoric of SNCC militants? Or was he making a general statement? We will never know. And just how much weight should be accorded to words spoken privately and never repeated publicly? (Had Lipset not written an article more than a year after the event, King’s words would have been lost forever.) My own view is that this dinner table remark can’t always bear the oversized burden imposed on it.”

Taking into consideration King’s response to the Six Day War, Kramer concludes that “it is an offense to history, if not to King’s memory, whenever someone today summons King’s ghost to offer unqualified support to Israel….” Whether Kramer’s advice will have any influence on those Israel apologists who are intent on using the Lipset quote to falsely equate criticism of Zionism with antisemitism is another matter.

Published on Medium in September 2017