Where are Cameron’s ground troops?

The House of Commons foreign affairs committee posed the following question to David Cameron, pinpointing what is arguably the central flaw in his plan for the UK to join the US bombing campaign in Syria: “Which ground forces will take, hold, and administer territories captured from Isil in Syria?”

In his response to the committee (pp.18–20) Cameron outlined the forces he claimed could achieve those objectives. As he explained in his statement to the House of Commons on 26 November: “we believe that there are around 70,000 Syrian opposition fighters, principally of the Free Syrian Army, who do not belong to extremist groups, and with whom we can co-ordinate attacks on ISIL.”

This 70,000 figure has been treated with scepticism if not outright derision in some quarters, not least among the anti-war left — most of whom, it must be said, have made little or no effort to get their heads around the complexities of the situation in Syria. They have proved all too ready to promote articles like this or this, apparently oblivious to the fact that by giving credence to such nonsense they were only undermining the case against war.

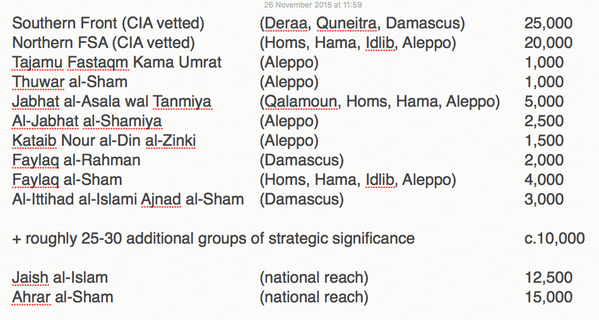

For an informed analysis of the anti-Assad opposition forces we should turn to Charles Lister, author of the recently-published 500-page study The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency. In response to the controversy over Cameron’s 70,000 figure, Lister tweeted a summary of the composition of the anti-Assad forces (see below) and presented a more detailed breakdown of the figures for the Spectator.

It is clear that Cameron actually underestimates the number of potential fighters against Daesh, as he leaves out the two main Islamist militias, Ahrar al-Sham and Jaish al-Islam, presumably because he thinks they don’t qualify as moderates. (For Ahrar al-Sham’s objections to this miscategorisation see here, and for their emphasis on their anti-Daesh credentials see here.) On Lister’s figures, the total number of anti-Assad fighters who are opposed to Daesh (including Ahrar al-Sham and Jaish al-Islam, but leaving out the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra and other jihadi groups) comes to more than 100,000.

But the priority of these anti-Assad fighters (the clue is in the name) is to fight Assad. As Lister tweeted in connection with his Spectator piece: “Worth emphasising — while these numbers do exist, they remain explicitly focused on fighting #Assad 1st, #ISIS 2nd. That won’t change.”

This is the gaping hole in Cameron’s strategy. He affects to believe that 70,000 anti-Assad fighters can be persuaded to prioritise the struggle against Daesh over resistance to Assad. Outlining his commitment to finding a “long-term solution” to the conflict in Syria, Cameron told the House of Commons: “I am clear that it cannot be achieved through a military assault on ISIL alone; it also requires the removal of Assad through a political transition. But I am also clear about the sequencing that needs to take place. This is an ISIL-first strategy.”

Here Cameron just repeats the fundamental error of the US government’s disastrous $500 million “train and equip” programme, which fell apart earlier this year precisely because it sought to organise an armed force from among anti-Assad fighters on the basis that they would adopt the principle of “ISIS first” and put the struggle against Assad on the back burner. John McCain identified the flaw in this programme when John Kerry appeared before Congress in September 2014 to justify it. He challenged Kerry:

“So we’re telling a young Syrian today … ‘You’ve got to fight Isis first. And by the way these barrel bombs that they’re dropping on you, and are massacring so many … we’re not going to do anything about it.’ … Isil first, that’s what you’re telling these young men — who really Assad has slaughtered their family members? How do you square that circle?”

The anti-Assad forces have a courageous record of resisting Daesh. Indeed, Cameron refers to their fierce battles with Daesh north of Aleppo in June this year — in which they received no support at all from US airstrikes. The US bombing campaign that Cameron is proposing to join has almost exclusively targeted Daesh forces in northern Syria. The anti-Assad resistance certainly aren’t going to head off to Raqqa and help Cameron destroy Daesh there until they’ve settled accounts with the regime in Damascus. In other words, the overthrow of Assad is the necessary precondition for the defeat of Daesh — the exact reverse of the sequence proposed by Cameron.

So, in the absence of the anti-Assad opposition forces, who has the US been relying on for its ground troops in the bombing campaign in northern Syria? They are in fact the Kurdish YPG, who together with a few minor and entirely subordinate Sunni Arab groups have been accorded the impressive title of the Syrian Democratic Forces by the US. In his Commons statement on 26 November, Cameron described these forces in glowing terms:

“Kurdish armed groups have shown themselves capable of taking territory, holding it and administering it, and, crucially, of relieving the suffering that the civilian population had endured under ISIL control. The Syrian Kurds have successfully defended Kurdish areas in northern Syria and retaken territory around the city of Kobane.”

Although for some reason Cameron didn’t see fit to mention it, these Kurdish forces are in reality the Syrian arm of the PKK, which has been a proscribed terrorist organisation in the UK since 2001. Here is how the PKK conducts the armed struggle in Turkey — killing unarmed, off-duty soldiers by shooting them in the head while they’re out doing their shopping. As for the PKK’s Syrian forces, earlier this year Amnesty International accused them of committing war crimes in the course of their fight against Daesh— “deliberately demolishing civilian homes, in some cases razing and burning entire villages, displacing their inhabitants with no justifiable military grounds … brazenly flouting international humanitarian law”.

Although for some reason Cameron didn’t see fit to mention it, these Kurdish forces are in reality the Syrian arm of the PKK, which has been a proscribed terrorist organisation in the UK since 2001. Here is how the PKK conducts the armed struggle in Turkey — killing unarmed, off-duty soldiers by shooting them in the head while they’re out doing their shopping. As for the PKK’s Syrian forces, earlier this year Amnesty International accused them of committing war crimes in the course of their fight against Daesh— “deliberately demolishing civilian homes, in some cases razing and burning entire villages, displacing their inhabitants with no justifiable military grounds … brazenly flouting international humanitarian law”.

So here, finally, we have the answer to the foreign affairs committee’s question to Cameron: “Which ground forces will take, hold, and administer territories captured from Isil in Syria?” These will be the forces of a proscribed terrorist organisation that has been accused of war crimes. It is difficult to see how this can end well.

This article was published on Medium, and (as “The holes in Britain’s anti-IS strategy”) by Middle East Eye, in December 2015