Imagine no Marxist analysis

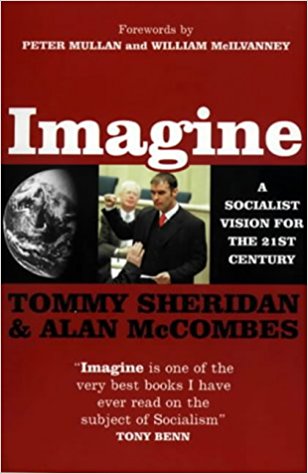

Tommy Sheridan and Alan McCombes, Imagine: A Socialist Vision for the 21st Century, Rebel Inc, 2000. Paperback, 252pp, £7.99.

Tommy Sheridan and Alan McCombes, Imagine: A Socialist Vision for the 21st Century, Rebel Inc, 2000. Paperback, 252pp, £7.99.

Last year I watched the television showing of a documentary film about the recording of John Lennon’s Imagine album. It had its moments (the expression on Phil Spector’s face as Yoko Ono gave him her advice on how to arrange one of the songs was particularly memorable), but the main impression was of the prevailing self-indulgence and woolly thinking of the period. The film’s best known scene is the one in which Lennon performs the album’s title track while seated at a white grand piano in one of the vast rooms of his mansion set in 70 acres of woodland near Ascot. “Imagine no possessions”, he croons. Well, yes John, you think to yourself, that would require a considerable feat of imagination on your part, wouldn’t it?

Nevertheless, “Imagine” has always been a hugely popular song. Though it only became a No.1 hit in the immediate aftermath of Lennon’s murder in 1980 (if you’re a pop star, dying is always a good career move), it regularly tops polls for the best single of all time. So I suppose you shouldn’t knock it. After all, the lyrics do contain some sort of basic socialist message, even if it is expressed in the form of sentimental doggerel.

In the introduction to the book reviewed here, co-authored by two leading members of the Scottish Socialist Party (SSP), Tommy Sheridan reveals that he proposed the title Imagine on the grounds that “the ideals that inspired Lennon to write his celebrated song seem to me to have even greater resonance today then ever before”. Even the book’s individual sections – Give Me Some Truth, Watching the Wheels Go Round, Power to the People – take their headings from various of the ex-Beatle’s compositions. You begin to wonder whether the authors are intent on developing an entirely new political ideology – Marxism-Lennonism.

There is nothing wrong with drawing on progressive aspects of mass culture in order to make socialist ideas comprehensible to a wider audience. But the problem with the book is that it reproduces, albeit in a more sophisticated fashion, the woolly thinking of Lennon’s song. Rather than presenting a Marxist analysis of the socialist project in an accessible form, it junks scientific socialism in favour of a sort of populist utopianism. Indeed, the authors quote favourably Oscar Wilde’s aphorism about it being a worthless map that doesn’t have the island of Utopia on it.

It’s not that Imagine doesn’t have its positive features. It is informative and well written – largely by Alan McCombes, I think it’s reasonable to assume – and provides a convincing exposé of the capitalist system along with a rather less detailed picture of an imagined socialist society.

The authors’ relative vagueness on the latter point – which George Galloway, in a review published in the SSP’s paper Scottish Socialist Voice, saw as a weakness – is in fact entirely compatible with the outlook of Marx himself, who famously repudiated any notion of “writing recipes for the cook-shops of the future”. However, Marx didn’t reject utopian socialism solely because he objected to idealist exercises in drawing up detailed blueprints for the post-capitalist millennium. Rather, he opposed the entire method of presenting a moral critique of the iniquities of capitalism and then counterposing to this a vision of a superior, socialist society.

Marx’s own method was to make an objective analysis of existing society, to identify tendencies within it which had progressive possibilities, and to integrate himself into these actual movements in order to assist them in realising their potential. Summarising the essence of scientific socialism “in opposition to utopian socialism”, in his “Conspectus of Bakunin’s Statism and Anarchy” of 1874, Marx explained that it consisted in “limiting its science to the knowledge of the social movement made by the people itself”. Marx had a very broad idea of a future post-capitalist society as “an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all”, and in the Critique of the Gotha Programme and elsewhere he outlined some of its general features, but he concentrated on the practical question of how working people, who are the subject of the socialist project, could move forward in the existing situation.

Central to Marx’s conception of socialism, therefore, was the collective organisation of the working class. As early as 1847 in The Poverty of Philosophy, his polemic against Proudhon, Marx argued that the real basis for socialism lay in the way in which workers combined in opposition to their employers – first of all on a temporary basis in sporadic industrial struggles and then in permanent trade unions, at which point the question of unified political action by the working class arose.

As Marx summed up his position: “Economic conditions had first transformed the mass of the people of the country into workers. The domination of capital has created for this mass a common situation, common interests. This mass is thus already a class as against capital, but not yet for itself. In the struggle, of which we have pointed out only a few phases, this mass becomes united, and constitutes itself as a class for itself. The interests it defends become class interests. But the struggle of class against class is a political struggle.”

Of course, this is not an automatic development. There is no inexorable progress of working class organisation, but rather an uneven process in which periods of advance are frequently followed by retreats and long years of stagnation. At the time that Marx was polemicising against Proudhon, he was able to point to the achievements of the British working class in organising both industrially, in its trade unions, and politically, in the Chartist movement. But with the defeat and eventual collapse of Chartism, working class political combination in its mass form was set back for decades in Britain, while industrial combination was largely restricted to the narrowly based craft unions.

From the late 1880s, though, the rise of the New Unionism brought industrial organisation to unskilled workers, while the formation of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1893 initiated a move towards a new working class political party. In the course of these developments the distinctive character of the 20th century British labour movement was established, with its mass-based trade unions and Labour Party. It is hardly necessary to point out that today, under the impact of defeats and de-industrialisation, this labour movement has been severely weakened.

The Militant Tendency, in which comrades Sheridan and McCombes received their political training, always claimed to follow the Marxist method, but distorted it into a mechanical schema according to which, under the impact of economic crisis, the masses would automatically flood into the traditional organisations of the class. The role of the “Marxists” was to be in there waiting for them when they arrived. This produced a rather passive, propagandist form of politics, but at least it led Militant to patient and systematic (if rather sectarian and elitist) work in the labour movement, and particularly within the Labour Party.

For a period, indeed, history seemed to vindicate their perspective. While most of the self-styled Marxist groups had abandoned the Labour Party in the 1960s, Militant remained ensconced there, so when a radicalisation took place in the party during the late ’70s as the rank and file revolted against the policies of the then Labour government, and the Bennite movement emerged as a pole of attraction within the Labour Party for those who wanted to see radical change in society, the Tendency cleaned up. By the early ’80s it was claiming as many as 8,000 members.

The reversals suffered by the left from the middle of that decade, however, threw Militant into theoretical disarray. Ten years ago, during the split between the supporters of Ted Grant and Peter Taaffe, the Taaffite majority (of which Sheridan and McCombes were part) argued that the Poll Tax rebellion was the harbinger of an upsurge of mass militancy, involving workers and youth who would not necessarily have any background in, or be attracted to, the traditional labour movement. Hence, they argued, the need to break from the Labour Party and establish an independent political organisation.

This perspective was largely demolished by the actual course of political developments in Britain. The mass movements predicted by Taaffe failed to materialise, while industrial conflict slumped to its lowest level for a century. But there is no sign of any re-evaluation on the part of Imagine’s authors. On the contrary, from a reading of this book you might think that Taaffe’s prognoses had been brilliantly confirmed, and that the 1990s were a period of intense class struggle.

We are told that the Anti Poll Tax campaign was followed by “the defeat of the Tory plans to privatise Scottish water. There have also been countless, more localised, workplace, community, and environmental struggles against exploitation and injustice…. these have included occupations of closure-threatened schools and community centres in Glasgow; occupations of factories such as Caterpillar in Lanarkshire and Glacier Metal in Glasgow; illegal defiance demos in Glasgow and Edinburgh against the Tory Criminal Justice Act; and environmental battles against motorway construction projects, genetically-modified crops, toxic-waste dumps, nuclear weapons, nuclear dumping, and opencast mines…. all of them, individually and combined, had a profound impact on those who participated in them and upon society as a whole”.

Even allowing that there has been a higher level of militancy in Scotland than elsewhere in Britain, you have to ask – does this really represent a sober, objective assessment of the level of political struggle and consciousness among working people over the past decade? Perhaps, instead of seeking inspiration in the songs of John Lennon, the authors should have taken the title of their book from Monty Python: Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.

Sheridan and McCombes, to be fair, are prepared to recognise the limitations of single issue campaigns: “When resistance to capitalism is divided into different fragments labelled ‘animal-rights protest’, ‘trade-union protest’, ‘anti-road protest’, ‘anti-nuclear protest’, each can be picked off and defeated, just as the individual strands of a rope can easily be snapped. But when the protests are woven together, like the strands of a rope, they become stronger and less easily broken.”

Fortuitously, such a solution is to hand in the growth of anti-capitalist demonstrations along the lines of that in Seattle: “This was no single-issue movement, focusing on a specific injustice; this was a protest directed at the entire global capitalist system. Since then, other similar actions have been organised in cities across the world. Protests, not just against poverty, not just against the destruction of the environment, not just against unemployment; but protests against all of these things, and against capitalism itself. This is of immense significance.”

Heady stuff. But this stirring description overlooks the point that participants in demonstrations against the actions of international financial institutions and multinational corporations are not necessarily committed to the abolition of capitalism as such, while those that are seem to be mainly influenced by a particularly mindless variety of anarchism. There is the further and more fundamental problem that the “anti-capitalism” of these protests, even on its broadest definition, actually represents the level of political consciousness of no more than a small minority of society. This is surely underlined by the low vote received by US presidential candidate Ralph Nader, who fought his campaign as an electoral expression of the spirit of Seattle. Is the situation that much more advanced in Scotland? I suspect not.

In addition to demonstrating against capitalism, Imagine encourages working people to support the Scottish Socialist Party in its struggle for reforms through the Scottish parliament. However, while the SSP is certainly a more substantial political force than the various Socialist Alliances in England and Wales, the reality is that the party barely has a presence outside of Scotland’s central belt, and even in its stronghold of Glasgow it is scarcely a viable electoral alternative to Labour. At present the SSP’s elected representatives number exactly one: Tommy Sheridan.

The political strategy put forward in the book thus boils down to radical protest movements plus the Scottish Socialist Party. This strikes me as a pretty flimsy basis for the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of socialism. If Marx taught us anything, it is that we can’t get very far without the basic organisations of the working class. But this is something the authors of Imagine seem to have lost sight of.

The trade unions, for example, so far as they rate a mention in the book, are reduced to just another vehicle for “protest” – and one which evidently takes second place to animal rights campaigns. As part of the optimistic scenario they present, Sheridan and McCombes stress the undoubted fact that workers form the large majority of society. They correctly point out that “the working class is not just made up of shipyard workers, coal miners, mill workers, car assembly workers, bricklayers and such-like…. It includes more or less everyone who works for an employer”. But the rather less happy fact that the decline of trade unionism has left most of these workers effectively atomised, lacking basic organisation and representation in the workplace, isn’t dealt with at all. In the circumstances, you might think that socialists’ energies would be better directed towards rebuilding the strength and influence of the trade union movement rather than joining in street protests with people who believe that the best way to fight the bourgeoisie is by smashing the windows of McDonald’s.

If the authors’ coverage of the trade unions is negligible, their analysis of the Labour Party is utterly hopeless. Chapter 11, “From Red Flag to White Rag”, begins with a satirical piece in which the Tory Party announces that capitalism is “irrelevant and out of date” and gets elected on a programme of nationalisation, heavy taxes on big business, close links with the trade unions etc, while those of its members who protest against this new line and call for a return to traditional Tory values are branded as traitors and expelled. An analogous process, we are invited to believe, has taken place in the Labour Party, which has abandoned its socialist ideology, severed its roots in the working class and become purely a party of capital. Even as a joke, this doesn’t stand up.

To make some elementary points, both Labour and the Tories are bourgeois parties, in the fundamental sense that they have pro-capitalist programmes. But in terms of membership and electoral support each has its base in different sections of society – Labour in the advanced sections of the working class (in particular the trade unions) and progressive sections of the middle class, the Tories among the reactionary middle class and backward workers. This creates different tensions within the two parties. For the Tory leadership, catering to the prejudices of their members and voters sometimes combines uneasily with their defence of bourgeois interests – as is the case at the moment over Europe. As far as Labour is concerned, the contradiction between working class aspirations and the bourgeois politics of the party leadership produces even more frequent and usually much sharper conflicts.

At the present time, due to the low level of class struggle and the general decline of political consciousness among working people (in other words, the erosion of the working class as a “class for itself”), opposition to the Labour leadership’s bourgeois politics has been enfeebled, allowing Blair and his clique to drive the party’s programme violently to the right. Ideally, they would like to take this process much further and destroy Labour as any kind of workers’ party, which would involve a rupture of the institutional link with the unions, together with a fusion with the Liberal Democrats and possibly pro-European Tories. If the Blairites were to achieve that objective, the prospects for any kind of socialist development in Britain would be set back even further. As yet, however, the Blairite “project” has by no means been accomplished (indeed, it seems to have been at least temporarily derailed), while the extreme rightward shift in programme has created a new range of tensions within the Labour Party.

The SSP’s response to this situation is a classic example of infantile leftism. Interviewed in the magazine Red Shift recently, SSP member Frances Curran insisted that “there is no prospect of mounting any alternative through Blair’s [sic] Labour Party”, and that far from encouraging oppositionists within the party the SSP has “appealed to the handful of individuals who are still in the Labour Party and who consider themselves socialists to join us”. Instead of demanding that the trade unions use their still considerable weight within the Labour Party to fight for working class policies, the SSP advocates that the unions should break from Labour – which would of course do the Blairites’ job for them. You can only suggest that the comrades take time out to consult Trotsky’s writings and study the advice he gave to the ILP after its split from the Labour Party in the 1930s.

The current situation, it should be obvious, is by no means one in which the overthrow of capitalism is directly on the agenda. With regard to the establishment of a socialist society, Marxists will have some sympathy with the country yokel who, asked by a passing motorist for directions to a distant town that could only be reached by a complicated route, replied, “Well, if I wanted to go there, I don’t think I’d start from here“. (This isn’t intended as a slur on the agricultural proletariat – I envisage the yokel as a member of the rural petty bourgeoisie.) However, what is clear is that, rather than concentrating on propaganda against capitalism and in favour of socialism, as the authors of Imagine do, the main task of Marxists in the current adverse situation is to wage a practical struggle to defend the movement that has been built by past generations.

In the Labour Party the way forward, as was cogently argued by Matthew Willgress in the last issue of What Next?, is by forming tactical alliances with those who may not agree with us over the need to destroy capitalism, but are opposed to at least some aspects of the Blairites’ ultra-right-wing programme and certainly do not share their aim of breaking up the labour movement. This involves campaigning around basic democratic issues and limited demands that enjoy majority support within the existing movement. Pursuing such a strategy may often be a wearying experience (believe me, I know), requiring what the American socialist Irving Howe, writing in the 1950s during another difficult period for socialists, described as “the heroism of tiredness”. However, unless the basic collective organisations of working people can be preserved and strengthened, the socialist transformation of society is indeed nothing but a utopia.

In conclusion, despite the critical character of this review, it must be said that Tommy Sheridan and Alan McCombes have written a readable book which will be welcomed by many of those who are already persuaded of its basic thesis (Tony Benn, for example, is quoted on the cover as commending Imagine as “one of the very best books I have ever read on the subject of socialism”). It may even convince some of those who have not yet been convinced that capitalism is a bad thing and socialism would be much better. But the authors’ apparent belief that a road to the socialist future can be found outside of the mass organisations of the working class is a self-consoling fantasy which has nothing in common with Marxism.

First published in What Next? in 2001