Fifty years since ‘Something Else’ (Or the decline and fall of the Kinks)

On the evidence of singles sales, 1967 represented the high point of the Kinks’ popularity and commercial success. The year began with Dead End Street at number 5 in the charts, and this was followed by the release of Waterloo Sunset, generally regarded as the Kinks’ and composer Ray Davies’ masterpiece, which reached number 2 in May. Death of a Clown – issued under Dave Davies’ name, but co-written with brother Ray and performed by the Kinks – made it to number 5 in August. The group went on to score a number 3 hit with Autumn Almanac in November. At the end of 1967 Dave Davies’ second “solo” single Susannah’s Still Alive, like its predecessor essentially a Kinks record with Dave on lead vocal, entered the charts. Less successful than Death of a Clown, it still made number 20 at the start of 1968.

So, over the course of one year, the Kinks effectively had five records in the UK charts. There were in addition two singles that didn’t make it into the shops here. Mr Pleasant was pressed for issue in the UK, with This Is Where I Belong as the B-side, but then withdrawn in favour of Waterloo Sunset (although it was released elsewhere in Europe, becoming a number 2 hit in the Netherlands). Lavender Hill, backed by Good Luck Charm, was recorded as the intended follow-up to Waterloo Sunset but shelved in favour of Autumn Almanac. While other groups often struggled to come up with a new single, the Kinks’ ability to generate potential hits exceeded the capacity of the charts to absorb them.

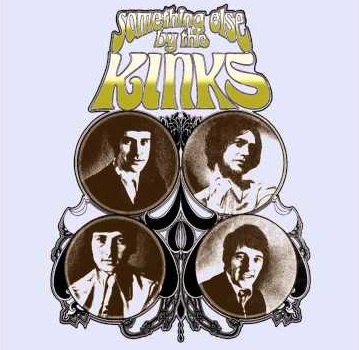

In September 1967, at the apparent height of their success, the group released the LP Something Else by The Kinks, which is now recognised as one of their four classic ’60s albums, preceded by Face to Face in 1966 and followed by The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society in 1968 and Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) the year after. Featuring 13 tracks selected from recordings made over the previous eighteen months in an almost bewildering range of styles, Something Else could possibly be criticised for a lack of musical unity but was hardly short on inventiveness or variety.

In September 1967, at the apparent height of their success, the group released the LP Something Else by The Kinks, which is now recognised as one of their four classic ’60s albums, preceded by Face to Face in 1966 and followed by The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society in 1968 and Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) the year after. Featuring 13 tracks selected from recordings made over the previous eighteen months in an almost bewildering range of styles, Something Else could possibly be criticised for a lack of musical unity but was hardly short on inventiveness or variety.

The album opened with David Watts, which in other circumstances would have been an obvious choice for release as a single. (It was issued as the B-side of Autumn Almanac elsewhere in Europe, and the Jam had a minor hit with their cover version over a decade later.) The harpsichord-dominated Two Sisters, with its story of a married women trapped in domesticity and resenting the freedom enjoyed by her “wayward” single sister, took its inspiration from Ray Davies’s fraught relationship with brother Dave. In sharp musical contrast, No Return saw an unexpected foray into Latin rhythms. Harry Rag addressed the cross-class impact of nicotine addiction, and Tin Soldier Man offered a sour and perhaps rather smug commentary on the socially regimented life of some City type. Situation Vacant recounted the sad tale of a life destroyed by an interfering mother-in-law, while Lazy Old Sun, the most contemporary-sounding track on an album that was not obviously of its time, showed that the Kinks could do psychedelia.

The rather twee Afternoon Tea took Ray Davies’ cultivation of “Englishness” to the verge of self-parody but was saved by a good tune. In End of the Season, recorded during the Face to Face sessions the previous year, Ray adopted the persona of a posh bloke bemoaning the loss of his lover against the depressing background of the end of summer and Harold Wilson’s second election victory (“Now Labour’s in, I have no place to go”). Dave Davies’ burgeoning talent as a songwriter was well represented, with Death of a Clown and its B-side Love Me Till the Sun Shines both making an appearance, along with Funny Face, one of several songs Dave wrote at the time inspired by the traumatic, parentally-enforced breakup of his relationship with his first girlfriend Sue Sheehan. The album concluded with the mighty Waterloo Sunset.

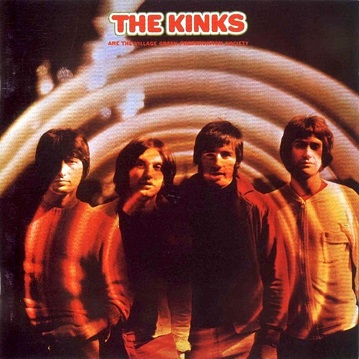

The release of Something Else marked the start of a period of quite astonishing creativity on the part of Ray Davies. In December 1967 he began work for the satirical TV show At the Eleventh Hour, which required him to contribute a song every week throughout its ten-week run, based on news reports mostly taken from his local paper the Hornsey Journal. (Did You See His Name? is the only one of these compositions to have been released, and ranks alongside the Kinks’ best recordings.) Songs just seemed to come pouring out, to the extent that Davies wanted to make 1968’s Village Green Preservation Society a 20-track double album in order to accommodate the material he’d written. The Kinks’ record company, Pye, unfortunately rejected that proposal, but Davies still crammed 15 impressive compositions onto an album that is now rightly seen as the Kinks’ greatest musical achievement.

The release of Something Else marked the start of a period of quite astonishing creativity on the part of Ray Davies. In December 1967 he began work for the satirical TV show At the Eleventh Hour, which required him to contribute a song every week throughout its ten-week run, based on news reports mostly taken from his local paper the Hornsey Journal. (Did You See His Name? is the only one of these compositions to have been released, and ranks alongside the Kinks’ best recordings.) Songs just seemed to come pouring out, to the extent that Davies wanted to make 1968’s Village Green Preservation Society a 20-track double album in order to accommodate the material he’d written. The Kinks’ record company, Pye, unfortunately rejected that proposal, but Davies still crammed 15 impressive compositions onto an album that is now rightly seen as the Kinks’ greatest musical achievement.

The irony is that this surge of musical inspiration coincided with the virtual collapse of the Kinks’ commercial success. In contrast to the group’s then still healthy singles sales, Something Else in fact sold very badly, spending only two weeks in the charts and peaking at number 35. Not only was this the worst-performing Kinks LP up to that point but it marked the end of the period (leaving aside various hits compilations) when they were able to produce top-selling albums. Its successors Village Green Preservation Society and Arthur were even bigger flops and failed to chart at all. The Kinks’ previously unerring ability to produce hit singles began to falter, too.

Between 1964 and the start of 1968 the group had registered an uninterrupted sequence of 14 top twenty hits (if you include the two singles issued in Dave Davies’ name). Wonderboy, released in April 1968, appeared set to continue this sequence. Musically, it’s up there with the great ’60s Kinks singles, and is said to have been a favourite of John Lennon, who during lunch at the Club dell’Aretusa in King’s Road reportedly demanded that Wonderboy be played over and over again. That may possibly have been in protest at the failure of the record-buying public to share his enthusiasm, however, because Wonderboy only reached number 36 in the charts.

This unexpected disaster, following as it did the equally disappointing response to Something Else, threatened to bring the Kinks’ career to an abrupt end. Rather than staging concerts featuring their new material, they found themselves on package tours giving perfunctory performances of their old hits in front of audiences who were there to see up-and-coming acts like the Herd and regarded the Kinks as a bit old hat, or reduced to playing in cabaret clubs to even more unreceptive punters.

The group’s fortunes rallied temporarily with their follow-up single, Days, released in June 1968. Clearly a conscious attempt by Ray to suppress his trademark quirkiness and irony in order to write a more straightforward love song, Days got to number 12 in the charts. Another Kinks classic, the record could easily have made it to number one or at least the top five a year earlier, but its relatively modest showing confirmed that the group’s star was now fading. Nine months later, in a more cynical attempt to restore their popular appeal, the Kinks released Plastic Man, which imitated the earlier style of Well Respected Man or Dedicated Follower of Fashion but without their satirical edge. A BBC ban resulting from the song’s shocking use of the word “bum” may also have contributed to poor sales and the record stalled at number 30. The next single Drivin’ failed to register in the charts, as did its brilliant successor Shangri-La, while Victoria – the final Kinks single of the ’60s – only reached number 33.

Dave Davies’ once promising solo career went down the tubes as well. The single Lincoln County flopped in 1968, as did its 1969 follow-up Hold My Hand. Pye Records, who had been pushing Dave to record an album to take advantage of the success of Death of a Clown, lost interest and the project was abandoned (though the material he recorded did emerge in various forms, some of it as Kinks B-sides of the period, and most recently on the CD Hidden Treasures).

What explains the Kinks’ sudden fall from grace, during a period that contradictorily marked the flowering of Ray Davies’ genius as a songwriter? The answer almost certainly lies in the bifurcation of popular music during 1967–8 into the separate and rival genres of pop and rock. Rock was “serious”, album-based and repudiated the traditional role of popular music as a branch of light entertainment. Aiming instead to create something more challenging for musicians and audiences alike, it sometimes degenerated into self-indulgence and pretentiousness. Pop was dismissed by rock fans as disposable singles-based fluff and abandoned to the teenyboppers. Consequently, the market for the intelligent pop produced by the Kinks shrunk disastrously. The rock fans wouldn’t buy it because it was pop, while it was too grown-up and sophisticated to appeal to the teenyboppers.

At one point it looked as though the Who would suffer the same fate – their 1968 singles Dogs and Magic Bus both sold poorly – but they were able to reinvent themselves with the release in 1969 of the “rock opera” Tommy. The Kinks’ own 1969 concept album Arthur, with its rather homely, downbeat tale of emigration to Australia, lacked an equivalent appeal to a rock audience.

The Kinks’ post-’60s career lies outside the scope of this article. Singles success returned briefly in 1970 with Lola, with which they scored a massive international hit, followed by Apeman. The group went through various phases subsequently, experimenting with a fusion of music and theatre for a time before emerging as a more conventional stadium rock band that achieved considerable popularity in the USA in the late ’70s and early ’80s. The Kinks finally broke up in 1996 and their only performance together after that was at Dave’s 50th birthday party the following year, though both Ray and Dave continue to pursue solo careers. It was in the late ’60s, however, that the Kinks reached their peak artistically. That they received such limited recognition at the time is a sad reflection on popular musical tastes of the period. At least this lapse has been rectified by the judgement of posterity.