An overdub has no choice – the Monkees and the making of Pleasant Valley Sunday

By Bob Pitt

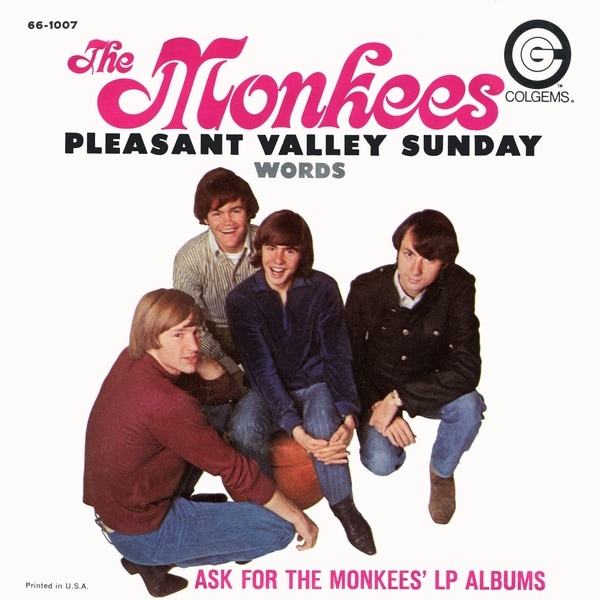

Half a century ago, on 10 July 1967, the Monkees’ single Pleasant Valley Sunday was released. Their recording of this classic Gerry Goffin/Carole King composition made it to number 3 in the US charts, becoming the fourth in a string of hits for the group that began with Last Train to Clarksville the previous year. Pleasant Valley Sunday was notable for being the first Monkees’ A-side to be recorded after the acrimonious split earlier in 1967 when they ousted their former musical supervisor Don Kirshner and seized creative control.

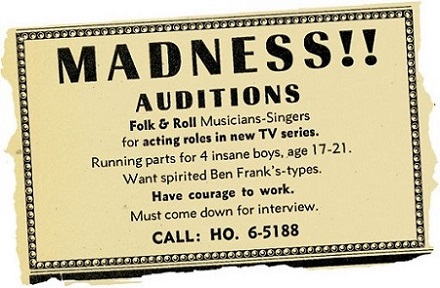

The Monkees still occupy a place in popular consciousness as the original manufactured group, the “Prefab Four” as they were scornfully dubbed at the time by a hostile British press. It is of course true that the group was “artificially” assembled in 1965 for the projected Screen Gems TV series The Monkees, after its producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider put an advert in the Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety inviting “insane boys, age 17–21” to audition for parts in the show. Over 400 aspiring pop stars responded to the call, but the producers finally settled on the quartet of Micky Dolenz, Davy Jones, Mike Nesmith and Peter Tork.

The Monkees still occupy a place in popular consciousness as the original manufactured group, the “Prefab Four” as they were scornfully dubbed at the time by a hostile British press. It is of course true that the group was “artificially” assembled in 1965 for the projected Screen Gems TV series The Monkees, after its producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider put an advert in the Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety inviting “insane boys, age 17–21” to audition for parts in the show. Over 400 aspiring pop stars responded to the call, but the producers finally settled on the quartet of Micky Dolenz, Davy Jones, Mike Nesmith and Peter Tork.

The original intention was for the four to function as a real group playing their own instruments, but progress during rehearsals was slow and a soundtrack for the TV show was urgently required. So Rafelson and Schneider drafted in Don Kirshner, the head of Screen Gems-Columbia Music, to oversee the Monkees’ recordings. Known as “the man with the golden ear” because of his ability to spot a hit, Kirshner also had a stable of writers – among them Neil Diamond, Gerry Goffin and Carole King, and Jeff Barry – who could be relied on to come up with commercially successful pop songs. As for the Monkees themselves, on the records that were issued in their name they were restricted to dubbing vocals over instrumental tracks recorded by session musicians under Kirshner’s supervision.

Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones saw themselves primarily as actors (Dolenz had found childhood fame as the eponymous hero of the TV series Circus Boy, while the Manchester-born Jones had appeared in Coronation Street before playing the Artful Dodger in the musical Oliver!) and they were initially happy to go along with this arrangement. Mike Nesmith and Peter Tork, however, had a background as working musicians and resented being sidelined from the recording process, with Nesmith in particular reacting with hostility to what he saw as their contemptuous treatment by Kirshner. He demanded, with increasing belligerence, that the Monkees should have the right to play on their own records.

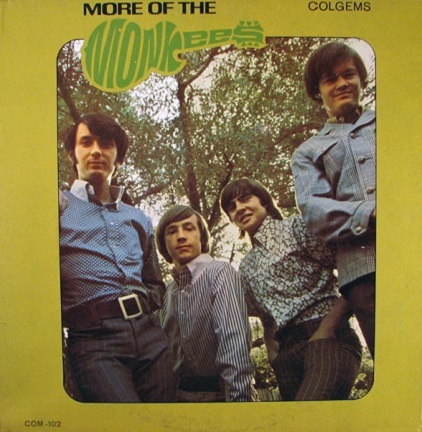

The release of their second LP More of the Monkees on 9 January 1967 intensified resentment at Kirshner’s behaviour. There had been no consultation with the group over the tracks that were included on the album, or over the cover photograph in which the group appeared in embarrassingly awful clothes as part of a deal Kirshner had signed with the JCPenney department store chain. In fact the Monkees hadn’t even seen a copy of the record until it appeared in the shops. “We had to buy the album to hear it,” a still aggrieved Peter Tork later recalled. “Somebody went across the street to the mall and bought the album.” To make matters worse, Kirshner had also contributed some rather self-aggrandising sleeve notes in which he gave precedence to the contributions of his team of songwriters and producers over those of the Monkees themselves.

The release of their second LP More of the Monkees on 9 January 1967 intensified resentment at Kirshner’s behaviour. There had been no consultation with the group over the tracks that were included on the album, or over the cover photograph in which the group appeared in embarrassingly awful clothes as part of a deal Kirshner had signed with the JCPenney department store chain. In fact the Monkees hadn’t even seen a copy of the record until it appeared in the shops. “We had to buy the album to hear it,” a still aggrieved Peter Tork later recalled. “Somebody went across the street to the mall and bought the album.” To make matters worse, Kirshner had also contributed some rather self-aggrandising sleeve notes in which he gave precedence to the contributions of his team of songwriters and producers over those of the Monkees themselves.

In the UK the first episode of The Monkees TV series was broadcast on BBC1 on 31 December 1966. By the middle of January the group’s second single, the Neil Diamond composition I’m A Believer, had reached number 1 in the charts and the country was gripped by Monkeemania. For some critics, however, who dismissed the Monkees as an inferior imitation of the Beatles, their negative opinion was only reinforced by reports that the group were replaced by session musicians on their recordings. In an article published in the 15 January edition of the Sunday Mirror and headlined “a disgrace to the pop world”, the paper’s show business editor, a former dance band trombonist named Jack Bentley, denounced the Monkees as talentless frauds who mimed to music played by others. An outraged Bentley wrote:

This idiotic Monkee business – was ever a bigger spoof pulled on the pop world? …

The group’s musical fame is the result of a gigantic Hollywood TV publicity campaign. The Americans never forgave the Beatles for not being born there, so they decided to create their own. Even the Monkees’ television show is a prolonged imitation from the Beatles’ films. The fact that the big spoof came off, making the Monkees No.1 on both sides of the Atlantic, is a downright disgrace, an insult to pop fans, a threat to the pop business as a whole and a deterrent to any youngster who has a musical future in mind.

Musicians like myself spent years of hard practice before being able to earn a living then comparable to a grocery assistant’s. Even the lowliest pop group in Britain can’t get a job without some hard work…. Yet here are a bunch of kids trading on other people’s talents and cashing in on millions. Who can ever regard that No.1 spot with any seriousness again? Musically, comparing the Monkees with the Beatles is like comparing a milk float with a Mercedes.

The fact that the Monkees were performing live before big audiences at US concerts where they did play their own instruments failed to sway Bentley. He accused them of “relying on the screaming of the fans for a big cover-up”.

It was the day after the publication of this rant that the Monkees held their first studio session as a functioning band. Kirshner had reluctantly agreed that they could record some material of their own choice, to which they could provide the accompaniment, even though he had no intention of releasing the results. Nesmith recruited Chip Douglas of the Turtles as their producer. Douglas was responsible for arranging his group’s number 1 hit Happy Together, although this hadn’t yet been released when he and the Monkees entered the studio on 16 January. They began work on All of Your Toys, composed by Nesmith’s friend Bill Martin, which they hoped would be their third single, with the Nesmith song A Girl I Knew Somewhere as the intended B-side. However, All of Your Toys fell foul of the rule that all songs on Monkees records had to be published by Screen Gems, and Martin’s publishing company refused to release the rights to his composition. (All of Your Toys remained unheard until 1987 when it appeared on the outtakes compilation Missing Links.)

Faced with the threat of rebellion in the ranks, Kirshner flew out to the West Coast in late January 1967 to formally present the Monkees with gold records along with a quarter-of-a-million dollar royalty cheque for each of them. At a meeting in Kishner’s private bungalow at the Beverley Hills Hotel, during a row provoked by Kirshner’s insistence on maintaining control over the Monkees’ recordings, a furious Mike Nesmith famously punched a hole through the wall. “Donny was there with his attorney,” Micky Dolenz recalled, “basically presenting us with this money and saying, in so many words, ‘Why don’t you shut up and cash the check?’ And that’s not the sort of thing you said to Mike Nesmith at the time. To be honest, I couldn’t have cared less. I was 20 years old, making money. But Mike led this revolt, and out of camaraderie, we all went along.”

Faced with the threat of rebellion in the ranks, Kirshner flew out to the West Coast in late January 1967 to formally present the Monkees with gold records along with a quarter-of-a-million dollar royalty cheque for each of them. At a meeting in Kishner’s private bungalow at the Beverley Hills Hotel, during a row provoked by Kirshner’s insistence on maintaining control over the Monkees’ recordings, a furious Mike Nesmith famously punched a hole through the wall. “Donny was there with his attorney,” Micky Dolenz recalled, “basically presenting us with this money and saying, in so many words, ‘Why don’t you shut up and cash the check?’ And that’s not the sort of thing you said to Mike Nesmith at the time. To be honest, I couldn’t have cared less. I was 20 years old, making money. But Mike led this revolt, and out of camaraderie, we all went along.”

The least rebellious of the Monkees, and the most amenable to continued control by Kirshner, was Davy Jones. So in early February, behind the backs of the other Monkees, Kirshner arranged for Jones to attend studio sessions in New York where he overdubbed vocals onto prerecorded backing tracks produced by Jeff Barry. The songs included Neil Diamond’s A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You and a Barry composition, She Hangs Out. These were effectively Davy Jones rather than Monkees records, because no other members of the group appeared on the recordings, even on backing vocals. They were frozen out completely by Kirshner, who was obviously intent on showing these ingrates who was boss.

But Kirshner overreached himself. He had A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You pressed as a single, with She Hangs Out as the B-side, and released it without authorisation. Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider called for his removal as the Monkees’ musical supervisor, Screen Gems acceded to their demand, and Kirshner was out. The single was then withdrawn and reissued with the Monkees’ self-recorded A Girl I Knew Somewhere as the B-side. Kirshner didn’t suffer too badly, mind you, because he won a rumoured $12 million settlement after suing for breach of contract. He went on to have a major success with another TV show that featured a pop group, the animated comedy series The Archie Show, evidently reasoning that manufacturing a group from cartoon characters had the advantage that they couldn’t rise up and demand creative autonomy. “I said ‘screw the Monkees, I want a band that won’t talk back’,” Kirshner explained.

In their book Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor claim that “it is hard to see what the Monkees really achieved by liberating themselves from Kirshner’s control. As a pop phenomenon, a band created for a mere television show, they made some really good pop records. As an authentic band, they were rarely more than humdrum.” This argument serves to bolster the book’s central thesis, namely that the search for musical authenticity, of which the Monkees’ insistence on playing their own instruments and controlling their recordings is held to be an example, is largely spurious. But as a musical judgement it is surely untenable.

Freed from the grip of Kirshner, the Monkees set about recording their third album, Headquarters. Apart from producer Chip Douglas and others helping out on bass, and the addition of cello and French horn on one track, the Monkees played all the instruments themselves, in defiance of the critics who claimed they weren’t a real band. As Bob Stanley observes in Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop: “The results should have been a disaster, DIY at best; instead, they produced Headquarters, quite the most morning-fresh album of the era, with tinges of country and folk rock and a tangible sense of gleeful freedom…. It’s a miracle of a record.” The Monkees’ revolt was vindicated when Headquarters was released to popular acclaim. Although it sold fewer copies than the first two Kirshner-supervised albums, it still reached number 1 in the US charts (number 2 in Britain).

Freed from the grip of Kirshner, the Monkees set about recording their third album, Headquarters. Apart from producer Chip Douglas and others helping out on bass, and the addition of cello and French horn on one track, the Monkees played all the instruments themselves, in defiance of the critics who claimed they weren’t a real band. As Bob Stanley observes in Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop: “The results should have been a disaster, DIY at best; instead, they produced Headquarters, quite the most morning-fresh album of the era, with tinges of country and folk rock and a tangible sense of gleeful freedom…. It’s a miracle of a record.” The Monkees’ revolt was vindicated when Headquarters was released to popular acclaim. Although it sold fewer copies than the first two Kirshner-supervised albums, it still reached number 1 in the US charts (number 2 in Britain).

In the UK, to coincide with the Monkees’ arrival for series of concerts at the Empire Pool Wembley, a single was released from Headquarters – the Micky Dolenz composition Randy Scouse Git (renamed Alternate Title to avoid offending record-buyers and forestall a BBC radio ban). Inspired by Dolenz’s experiences during a promotional visit to the UK in February 1967, the song contains allusions to meeting the Beatles (“the four kings of EMI”) and Dolenz’s future wife, Samantha Juste of Top of the Pops fame (“the being known as Wonder Girl”). The title of the song was taken from Johnny Speight’s sitcom Till Death Us Do Part, referencing the verbal abuse directed by Warren Mitchell’s character, the comically exaggerated reactionary loudmouth Alf Garnett, towards his Liverpudlian socialist son-in-law, played by Tony Booth.

Alternate Title got to number 2 in the UK charts, but was not released as a single in the US. Although arguably one of the Monkees’ great records, it was not obvious hit material, and the Till Death Us Do Part reference was perhaps rather recondite for American record-buyers. So the Monkees, with Chip Douglas’s assistance, set about recording a new single. There was some serious pressure on here because, although Headquarters had proved successful, the true test of the Monkees’ continued commercial viability without Kirshner was whether they could still have a hit single. They chose Pleasant Valley Sunday, composed by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, who had already written several songs for the group, notably Take A Giant Step, which was issued as the B-side of Last Train To Clarksville.

It might seem contradictory that as their first self-recorded A-side the Monkees should select a composition by two of the leading figures from Don Kirshner’s stable of commercial “Brill Building” songwriters, but by then the angry reaction against Kirshner and his methods had begun to fade somewhat. The Monkees also relaxed their purist insistence on playing all their own instruments which had been a feature of Headquarters, with the session musician Eddie Hoh now replacing Micky Dolenz on drums.

The group began work on Pleasant Valley Sunday over the weekend following their 9 June 1967 performance before an 18,000-strong audience at the Hollywood Bowl and they completed it by the following Tuesday. As Andrew Hickey writes in Monkee Music:

If ever proof were needed that the Monkees were capable of producing great pop records without the involvement of Don Kirshner, this is it. With an instrumental track by Tork, Nesmith, Douglas and Hoh (with additional acoustic guitar by Bill Chadwick and possibly Dolenz), this shows that the band could, when left to their own devices, create spectacular pop singles. Every band member gets to shine here – Dolenz of course takes the lead vocal, and does his usual superb job.

The emptiness of life in suburbia, which forms the theme of Pleasant Valley Sunday, might seem an easy target. Nor was it the first time the subject had been addressed in a pop song. John Carter and Geoff Stephens’ Semi-Detached Suburban Mr James (“I can see you in the morning time/Washing day, the weather’s fine/Hanging things upon the line/As your life slips away”) had been a UK hit for Manfred Mann in 1966. Indeed Andrew Hickey, who thinks the strength of Pleasant Valley Sunday lies in the performance, production and arrangement of what is otherwise a “relatively weak” song, dismisses Goffin’s lyrics as “just an example of the mid-60s tendency to cruelly mock people for daring to want a comfortable life”.

But the song had an edge that derived from personal experience. In 1964 Goffin and King had taken advantage of the new-found affluence resulting from their songwriting royalties (the couple had scored a succession of top 20 hits starting with the Shirelles’ Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow? in 1961) to move out of New York to West Orange in New Jersey. “Gerry did not enjoy living in the suburbs”, King observed ruefully in her autobiography, “an opinion he vigorously documented in a song called Pleasant Valley Sunday.” The lyric specifically refers to Pleasant Valley Way in West Orange, whose name Goffin took as symbolising the blandness of suburban existence.

But the song had an edge that derived from personal experience. In 1964 Goffin and King had taken advantage of the new-found affluence resulting from their songwriting royalties (the couple had scored a succession of top 20 hits starting with the Shirelles’ Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow? in 1961) to move out of New York to West Orange in New Jersey. “Gerry did not enjoy living in the suburbs”, King observed ruefully in her autobiography, “an opinion he vigorously documented in a song called Pleasant Valley Sunday.” The lyric specifically refers to Pleasant Valley Way in West Orange, whose name Goffin took as symbolising the blandness of suburban existence.

A forceful pop/rock number that drives towards a dramatic reverb-heavy conclusion, Pleasant Valley Sunday’s most prominent feature is the distinctive lead guitar figure that was created by Chip Douglas. Douglas subsequently told Monkees historian Andrew Sandoval, author of the definitive study The Monkees: The Day-by-Day Story of the 60s TV Pop Sensation, that it was “kind of an offshoot of the Beatles song I Want To Tell You”. However, Mike Nesmith who played it on the record, recalled: “Chip said, ‘We need a riff like in Paperback Writer, Last Train To Clarksville, Day Tripper. How does this riff sound?’ He played the riff to Pleasant Valley Sunday.” Certainly Paperback Writer has always struck me as the more obvious inspiration for the riff.

Although years later he could remember only that it involved some alterations to the bridge, Douglas’s rearrangement of the song did involve some tinkering with the lyrics, “mistakenly transposing two lines” as Sandoval summarised it. This wouldn’t have gone down at all well with Goffin and King, who were insistent that Gerry’s carefully crafted words should be sung as written. In 1966 they had demanded (and got) the withdrawal of Goldie Zelkowitz’s original version of Goin’ Back because of the unauthorised changes to the lyrics made by producer Andrew Loog Oldham.

Although years later he could remember only that it involved some alterations to the bridge, Douglas’s rearrangement of the song did involve some tinkering with the lyrics, “mistakenly transposing two lines” as Sandoval summarised it. This wouldn’t have gone down at all well with Goffin and King, who were insistent that Gerry’s carefully crafted words should be sung as written. In 1966 they had demanded (and got) the withdrawal of Goldie Zelkowitz’s original version of Goin’ Back because of the unauthorised changes to the lyrics made by producer Andrew Loog Oldham.

Douglas told Andrew Sandoval: “I do remember seeing Carole King up at the Screen Gems office from across the room after we did Pleasant Valley Sunday. She kind of gave me this dirty look. I thought, ‘Was it that line that I got wrong, perhaps? Or didn’t she like the guitar intro?’ It was faster, definitely, than the way she had done it. She had a more laidback way of doing stuff.”

Since that interview Carole King’s demo of Pleasant Valley Sunday has surfaced, having been officially released on her 2012 CD The Legendary Demos, so we can now compare it with the Monkees’ recording. King’s original is indeed more laidback than Douglas’s aggressive guitar-driven reinterpretation. Even in King’s slower version it is quite a short song, though, coming in at under two-and-a-half minutes. In Douglas’s faster arrangement it would have been still shorter if he’d stuck to the original format. So he needed to extend the structure.

In King’s version the bridge goes: “Creature comfort goals/Can only numb my soul/I need a change of scenery/My thoughts all seem to stray/To places far away/I don’t ever want to see/Another Pleasant Valley Sunday….” The song then gradually fades out, with the repetition of the phrase “another Pleasant Valley Sunday”. But in Douglas’s expanded arrangement the bridge is followed by a return to the guitar riff and then a passage of wordless vocals, so the segue from “I never want to see” to “another Pleasant Valley Sunday” was impossible. He therefore changed the lyrics around to read: “Creature comfort goals/They only numb my soul/And make it hard for me to see/My thoughts all seem to stray/To places far away/I need a change of scenery.”

You can understand why King might have objected to this. The transposition of the two lines (which we can now see was intentional) not only detracted from the sharpness of the original lyrics, which culminated in the heartfelt cry of “I don’t ever want to see another Pleasant Valley Sunday”, but it rendered them partially incomprehensible. I mean, creature comfort goals might well numb your soul, but it’s not entirely clear why they should also interfere with your eyesight. (Later King evidently overcame her objections to Douglas’s rearrangement of her song. Her performance of Pleasant Valley Sunday on her 2005 live album The Living Room Tour exactly follows the Monkees’ version.)

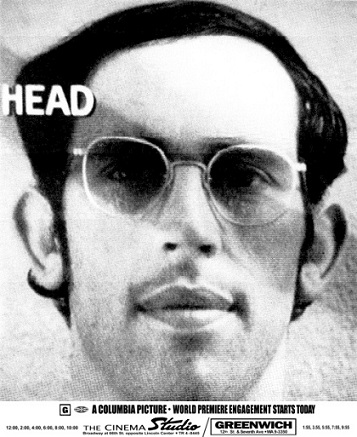

Despite their resentment at the restructuring of their composition, Goffin and King continued to provide material for the Monkees, their most notable contribution being Porpoise Song, which included a biting reference (“A face, a voice/An overdub has no choice”) to the days when the group was still under Don Kirshner’s thumb. Porpoise Song served as the theme to Head, the commercially disastrous 1968 Monkees movie that effectively dealt a death blow to their 60s career. Mocking the group’s rise to pop stardom (“Hey, hey, we are The Monkees/You know we love to please/A manufactured image/With no philosophies”), Head dispensed with linear narrative in favour of an episodic and surrealistic approach that alienated the Monkees’ established teenage fanbase without having any compensatory appeal to the counterculture crowd who were presumably the film’s target audience.

Despite their resentment at the restructuring of their composition, Goffin and King continued to provide material for the Monkees, their most notable contribution being Porpoise Song, which included a biting reference (“A face, a voice/An overdub has no choice”) to the days when the group was still under Don Kirshner’s thumb. Porpoise Song served as the theme to Head, the commercially disastrous 1968 Monkees movie that effectively dealt a death blow to their 60s career. Mocking the group’s rise to pop stardom (“Hey, hey, we are The Monkees/You know we love to please/A manufactured image/With no philosophies”), Head dispensed with linear narrative in favour of an episodic and surrealistic approach that alienated the Monkees’ established teenage fanbase without having any compensatory appeal to the counterculture crowd who were presumably the film’s target audience.

The Monkees TV show had been cancelled earlier in 1968 at the end of its second season, and although the Monkees persevered as a group for a couple more years, shedding members as they went, their musically uneven efforts met with declining commercial success. You And I, a track from their 1969 album Instant Replay, which reached a lowly number 32 in the US and didn’t even register in the UK charts, offered a bitter commentary on the transitory nature of fame: “In a year or maybe two/We’ll be gone and someone new/Will take our place/There’ll be another song, another voice/Another pretty face.” During their brief period at the top, however, the Monkees produced a solid body of musically intelligent pop that still holds up today. Pleasant Valley Sunday stands as one of the most impressive of their achievements.

First published on Medium in July 2017