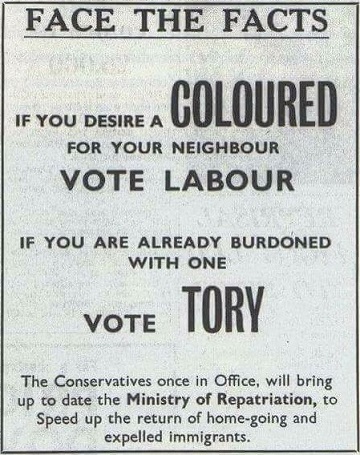

‘If you desire a coloured for your neighbour vote Labour’ – the origins of a racist leaflet

This appalling leaflet is regularly posted on social media as a shocking example of racist political propaganda from the past. But who produced it, and when and where was it originally used? Nobody has yet come up with a satisfactory answer.

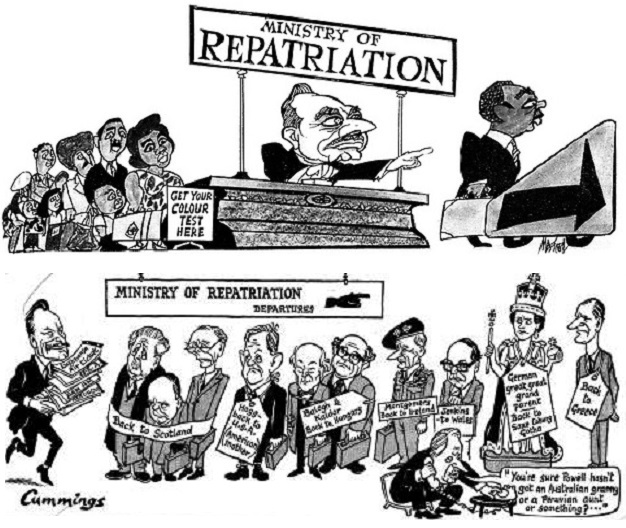

The leaflet is usually blamed on the Conservative Party. It does after all urge the electorate to “Vote Tory”. But Lewis Baston is undoubtedly correct in rejecting this attribution. The crudely produced flyer, with its random use of capital letters and misspelling of “burdened”, is obviously not the work of a mainstream political party. Furthermore the promise to “bring up to date the Ministry of Repatriation” makes no sense. There was no such ministry in existence and the Tories never adopted a policy of establishing one. On top of which, an official leaflet would call on the electorate to “Vote Conservative”, not Tory.

As for the date of the leaflet, it is usually given as 1964 (see here, here and here). This is evidently because the slogan “if you desire a coloured for your neighbour vote Labour” achieved prominence in an even more offensive variant during the notorious campaign in Smethwick in that year’s general election. However the 1964 date doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. The leaflet states that the Ministry of Repatriation policy will be introduced by the Tories “once in Office”. But in 1964 the Tories already were in office, and had been since 1951. Also, the proposal that the Tories should establish a Ministry of Repatriation was first made by Enoch Powell in a widely-reported speech from November 1968, and therefore could hardly have appeared in a leaflet produced four years earlier.

So the leaflet is clearly from an election which took place after November 1968, in circumstances where the Tories were in opposition. It doesn’t take a genius to work out that this must have been the general election of June 1970.

Some earlier commentators have identified Lambeth in south London as the area where the flyer was distributed. Here they are on firmer ground. It turns out that there is a press cutting in the Borough of Lambeth archives which features the leaflet. The cutting is accompanied by the information that the leaflet was “republished by the South London Press as an example of the local reaction to David (Lord) Pitt standing as the first Afro-Caribbean Labour party candidate for Clapham”. The date is given as 1966, but David Pitt in fact stood in Clapham in the 1970 general election. Further research confirms that this is indeed where and when the leaflet was circulated.

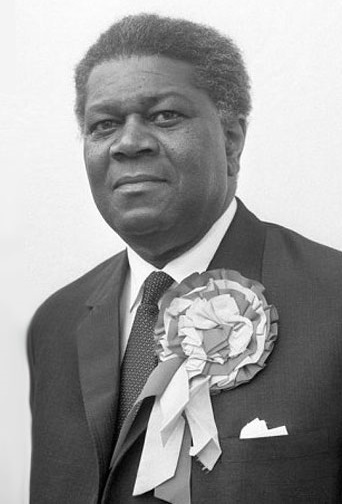

David Pitt was born in 1913 in Grenada, where he became active in socialist and anti-colonial politics. He trained as a doctor in Edinburgh and in 1947 moved permanently to the UK, establishing a medical practice in Euston. He joined the Labour Party and in the 1959 general election stood unsuccessfully as a parliamentary candidate for Hampstead, in a campaign marred by racism and death threats. In 1961 he was elected to represent Hackney on the London County Council. Pitt launched the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination with C.L.R. James and others in 1964 to lobby for race relations legislation. That year he was elected to the LCC’s successor the Greater London Council, becoming GLC deputy chair in 1969.

David Pitt was born in 1913 in Grenada, where he became active in socialist and anti-colonial politics. He trained as a doctor in Edinburgh and in 1947 moved permanently to the UK, establishing a medical practice in Euston. He joined the Labour Party and in the 1959 general election stood unsuccessfully as a parliamentary candidate for Hampstead, in a campaign marred by racism and death threats. In 1961 he was elected to represent Hackney on the London County Council. Pitt launched the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination with C.L.R. James and others in 1964 to lobby for race relations legislation. That year he was elected to the LCC’s successor the Greater London Council, becoming GLC deputy chair in 1969.

If successful in Clapham in 1970, Pitt would have been the first politician of African-Caribbean heritage to be elected to parliament. On the face of it, the prospects were bright. Having won Clapham in nearly every post-war election, with the single exception of 1959, Labour was thought to have a good chance of retaining the seat, and Pitt himself appeared confident of victory, telling the press: “Clapham is a natural Labour seat and I think the real Labour majority is far greater than that of the last election. Clapham has become one of the showpieces in showing the world what this country can do in race relations.”

The campaign itself appeared to go well. “Observers in Clapham who witnessed Dr Pitt’s door-to-door canvassing”, it was reported (Race Today, July 1970), “all saw an affable candidate being greeted as might any other Labour candidate campaigning in a ‘safe’ Labour seat. At public meetings too, who would have suspected that behind the many white voters in the audience who were happily singing ‘We shall overcome’ with David Pitt and Cy Grant were Labour voters harbouring doubts about their candidate’s colour?”

Yet that proved to be the case. When the result was declared, Pitt had finished second to the Tory candidate, William Shelton, who won by the surprisingly wide margin of 49.8 per cent to 40.4 per cent.

Pitt subsequently wrote to the Times arguing that there were a number of factors contributing to his failure to hold the seat for Labour and that he “would have won Clapham” if he had been allowed several months to campaign, rather than being selected on the eve of the election following the resignation of the sitting MP. Pitt stated: “I think it is therefore fair to conclude that race played only a small part in my defeat in Clapham and I think we will be doing the community a grave disservice if we rated it any higher.” No doubt Pitt had his own reasons for drawing this conclusion — concern that constituency parties might be deterred from selecting further black candidates was probably one of them — but his argument was unpersuasive. As Muhammad Anwar (Race and Politics, 1986, p.99) noted:

“David Pitt was defeated with a 10.2 per cent swing from Labour to Conservative, over twice the swing in the surrounding constituencies. The Labour vote was down (11.2 per cent) compared with the national loss of 4.9 per cent and the total turnout was down (11 per cent). The conclusion seems inescapable that some Labour voters did not vote because their candidate was black … even if one takes into account local circumstances — he was nominated for this constituency only three weeks before the election, he faced a locally well-known Conservative, and he did not himself live in the constituency — it is difficult to explain in any other way other than his colour the degree of his rejection by Labour voters.”

Part of the campaign that was launched against Pitt as soon as his selection was announced was to portray him as a “Black Power advocate” (although the parallels between this mainstream Labour politician and Stokely Carmichael were not immediately obvious). Pitt responded by arguing: “I believe in Black Power so far as it is making blacks aware of their contribution to society, but I do not advocate American Black Power which is based on violence.” This argument was rejected by his opponents. A letter published in the South London Press two days before the election demanded: “What simple minded individuals in the Clapham Labour Party nominated Dr David Pitt as prospective party candidate for this constituency? If Dr Pitt or his sponsors think that they can support Black Power without risking or courting violence they must be very stupid.”

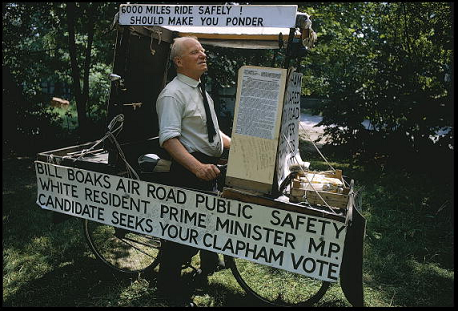

Another candidate to contest the Clapham seat was the independent, Bill Boaks, who announced that he was standing “on behalf of white residents” – the obvious implication being that these residents could not be represented effectively by a black MP. Boaks was one of those individuals who see elections as a vehicle for advertising their personal eccentricities – he was a sort of right-wing racist version of Screaming Lord Sutch – and in his repeated electoral forays Boaks never received more than a derisory number of votes. In Clapham in 1970, where he stood under the banner of Air Road Public Safety White Resident, he got just 80 votes (0.24 per cent). This didn’t prevent the South London Press from splashing the announcement of Boaks’ crank candidacy on their front page under the headline “White-resident candidate to fight Dr Pitt”.

Another candidate to contest the Clapham seat was the independent, Bill Boaks, who announced that he was standing “on behalf of white residents” – the obvious implication being that these residents could not be represented effectively by a black MP. Boaks was one of those individuals who see elections as a vehicle for advertising their personal eccentricities – he was a sort of right-wing racist version of Screaming Lord Sutch – and in his repeated electoral forays Boaks never received more than a derisory number of votes. In Clapham in 1970, where he stood under the banner of Air Road Public Safety White Resident, he got just 80 votes (0.24 per cent). This didn’t prevent the South London Press from splashing the announcement of Boaks’ crank candidacy on their front page under the headline “White-resident candidate to fight Dr Pitt”.

The leaflet under consideration here was a particularly virulent strand in this pattern of prejudice against Pitt, circulated with the clear intention of blocking the election of a black candidate by whipping up racist hostility towards Labour. Understandably, the appearance of the leaflet during the election campaign caused a scandal. Following Pitt’s defeat, it was reproduced on the front page of the 26 June edition of the South London Press under the headline “Racial leaflet row flares in Clapham”.

(As you can see the leaflet that was reproduced had the misspelled “burdoned” corrected by hand. This has been removed from the version that is in general circulation and appears at the top of this article. But the source is still the South London Press. The titles to items on the next page – “Total bail amounts to £6,000” and “Reprisal fight led to fines” — show through faintly.)

(As you can see the leaflet that was reproduced had the misspelled “burdoned” corrected by hand. This has been removed from the version that is in general circulation and appears at the top of this article. But the source is still the South London Press. The titles to items on the next page – “Total bail amounts to £6,000” and “Reprisal fight led to fines” — show through faintly.)

The paper reported: “The leaflet, carrying no identification of printer or publisher — which is required by law — was pushed through letter-boxes in Clapham on the eve of last week’s poll and a number were sent by post to electors who have coloured families as neighbours.” One recipient was quoted as saying: “I was utterly shocked and astounded. It looked like something from the Tories.”

This was presumably the impression the leaflet’s authors aimed to convey. However, as David Pitt told the South London Press: “This sort of thing is not done by the main parties but by some outside group.” Clapham Labour Party chair Colin Blau agreed: “There is no doubt that race lost us the election. A lot was being done in the area to stir up trouble. I don’t think, however, that this leaflet was an official Tory document.”

Labour did, though, blame the Tory Party for exploiting racist sentiment among the white majority population in order to secure their candidate’s victory. Colin Blau claimed that the Tories had made race a major issue in the constituency during their campaign and that their attacks on Pitt had a serious effect. Another Labour supporter, Peter Duffy, accused the Tories of drafting in party workers from safe seats to “peddle race hatred to the electorate of Clapham”. He said: “While I was out canvassing I received a number of complaints from people who strongly objected to the fact that the sole aim of these Tories was to drive home in the most derogatory terms that David Pitt was not white.”

Conservative agent Jean Lucas’s denial that her party had appealed to racism during the election was not exactly convincing. “The trouble is”, she observed, “that when people tell you on the doorstep ‘I’m not voting for a black man’ what do you say? Obviously we want as many as possible to vote for us.” However, Lucas assured the South London Press that her party had nothing to do with the offensive flyer: “All our publications carried the proper imprint. There was nothing racialist about any of them. I’ve no idea who could be responsible for this sort of objectionable leaflet.”

Who then did produce and distribute the leaflet? Probably some far-right group. But which one?

The National Front was active locally but its members were occupied in campaigning for their candidate in the neighbouring Battersea South constituency. The South London Press reported that the secretary of the NF’s Wandsworth branch, John Hammond, had told them some 34,000 leaflets in addressed envelopes were sent out in Battersea, but “none of the kind that went out in Clapham”. Another NF member said he “would be very doubtful” if the anonymous leaflet originated with his party: “Our name is always proudly printed on our propaganda.”

The veteran white supremacist Colin Jordan had a record of racist interventions in elections and had certainly used the “neighbour, Labour” slogan before, so on that basis he might qualify as a suspect. But Jordan’s neo-Nazi organisation the British Movement viewed the Conservatives as race traitors who were no better than Labour, and would have baulked at urging electors to “Vote Tory”, even to prevent the election of a black candidate. The Racial Preservation Society, most of whose members had joined the NF on its formation in 1967 but which maintained a separate existence as a propaganda organisation, is a more likely culprit. The RPS published lists of Tory MPs it considered “sound” on immigration, in order to encourage racist support for them, and promoted the demand “Powell for Premier”. But the truth is we don’t know who was responsible.

David Pitt went on to become the first black chair of the GLC and in 1975 was appointed to the House of Lords, where he continued to play a prominent role as an opponent of racism and defender of minority rights up until his death in 1994. But Clapham was the last parliamentary election Pitt contested. The defeat he suffered there had a wider impact by reinforcing the view held by some in the Labour Party that the selection of black candidates should be avoided because they were unelectable. It wasn’t until 1987 that two MPs of African-Caribbean heritage, Diane Abbott and Bernie Grant, took their seats in the House of Commons. Whoever was responsible for producing it, the racist Clapham leaflet made a significant contribution to this setback to the cause of black political representation.

Postscript

Since writing the above I’ve found evidence of the leaflet being being used elsewhere in London during the 1970 general election. Under the title “‘Race hate’ furore”, the Kensington Post reported in its 19 June edition that the leaflet had been circulated in the Kensington North constituency. The article included the additional detail that it was printed (appropriately) in green ink.

The Tory candidate, future home secretary Leon Brittan, angrily denounced the circulation of the flyer. “We did not put this leaflet out, nor would we have”, he declared. “I dissociate myself and my party from it entirely. I would not want to win a single vote as a result of this disgraceful literature.” Brittan asked the Post to tell electors that he repudiated “every word” in the leaflet.

Brittan suggested that the leaflet might have been produced by extremists of the left or right in an attempt to discredit the Tories. However, the Labour candidate, Bruce Douglas-Mann, while acknowledging that Brittan himself “would have nothing to do with racialist appeals of this kind”, added that the leaflet “indicates the kind of people behind the Tory Party. If the Conservatives were elected, they would find it difficult to resist pressure from their Powellite supporters.”

Kensington North had a history of far-right activity. Oswald Mosely contested the seat in the 1959 general election in the aftermath of the Notting Hill race riots, and Colin Jordan had used a house in Princedale Road as the base for a succession of fascist organisations. Douglas-Mann himself would have been regarded as a political enemy by the racist right because of his work as a local councillor defending black tenants, so he may well have been targeted for that reason.

However much they may have loathed Douglas-Mann, though, few adherents of the far right, which was generally characterised by an ingrained antisemitism, would have felt comfortable urging a vote for Leon Brittan. The fact that the leaflet was distributed in support of his campaign certainly excludes many far-right groups, but brings us no nearer to knowing who did produce it.

First published on Medium in May 2017