Now and Then: A critical analysis

Opinion is clearly polarised over Now and Then, the much-hyped single issued last week in the name of the Beatles. Some fans have responded ecstatically to the release of “the last Beatles song”, while others have expressed disappointment and resentment at the rather bland finished product. Beatles biographer Philip Norman, for example, has dismissed the recording as sounding like an ELO outtake from the ’70s. This may be unduly harsh, but you can see his point.

Lennon’s 1977 demo of Now and Then, on which the new version is based, has never been issued officially, but it was bootlegged years ago, so the song itself is familiar to many of us. I’ve always held a positive opinion of it. The lyrics, which appear to be a rather melancholy reflection on the tribulations of his relationship with Yoko, may be unexceptional, but it has an interesting musical structure.

The song begins with a 10-bar A theme in A minor (“I know it’s true, it’s all because of you”) which is then repeated (“And now and then, if we must start again”) before we come to the bridge. This consists of two 8-bar sections, B1 (“I don’t want to lose you”) and B2 (“But if you have to go away”), in E major. A restatement of the A theme would have been the obvious next step, but the song takes a less predictable turn, concluding with a 10-bar C theme (“Now and then, I miss you”) in G major. So instead of a conventional A-A-B-A format we have A-A-B1-B2-C.

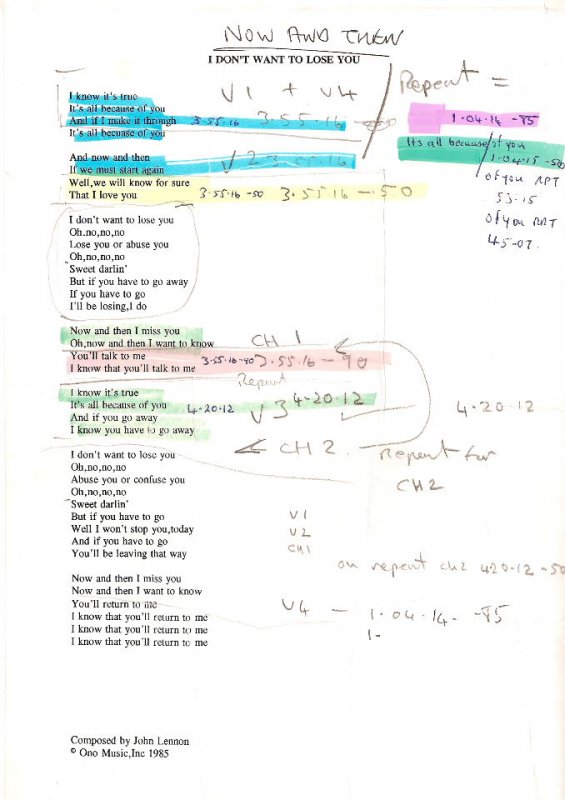

One problem here is that the B2 melody is beyond Lennon’s vocal range, so he strains to reach the top notes, which he delivers in a quavering off-pitch falsetto. Another is that he hadn’t yet finished the lyric and had to resort to scatting the last line of the bridge as a substitute for the missing words. No doubt for these reasons, the lyric sheet marked up by producer Jeff Lynne for the first attempt by the surviving Beatles to overdub Lennon’s demo back in 1994–5 indicates that it had been decided to omit the bridge.

But advance publicity for the new record emphasised that it was able to take advantage of the developments in technology since 1995. McCartney even referred, rather misleadingly as it turned out, to the use of AI. On that basis it should have been possible to fix these flaws in Lennon’s vocal. So I was looking forward to hearing McCartney’s solution to the bridge issue.

Unfortunately McCartney decided to solve the problem, as in 1994-5, by stripping the bridge out entirely. So the distinctive A-A-B1-B2-C sequence is reduced to A-A-C, simplifying the harmonic structure of the piece and rendering it rather plodding and predictable. Also, having junked a third of Lennon’s composition, McCartney was left with insufficient material for a full-length recording, and had to pad it out with an instrumental break (in which an allusion to its chord progression is all that remains of the rejected bridge).

This can hardly be viewed as an accurate and legitimate realisation of Lennon’s intentions when he wrote I Don’t Want to Lose You (the title under which Now and Then was copyrighted after his death — see above). In the accompanying promotional video McCartney says that he imagined asking Lennon about the plan to finish the song and was convinced it would have received his enthusiastic approval. But it is difficult to see how Lennon could have endorsed this butchery of his work.

Fan edits of Now and Then have been knocking around the internet for years (although they are currently being purged from Youtube, along with uploads of Lennon’s original demo, at the insistence of UMG). Despite lacking the cutting edge technology available to McCartney, I think they show rather more respect for Lennon’s legacy than his version does.

First published on Medium in November 2023