Review of Richard Seymour’s ‘Unhitched’

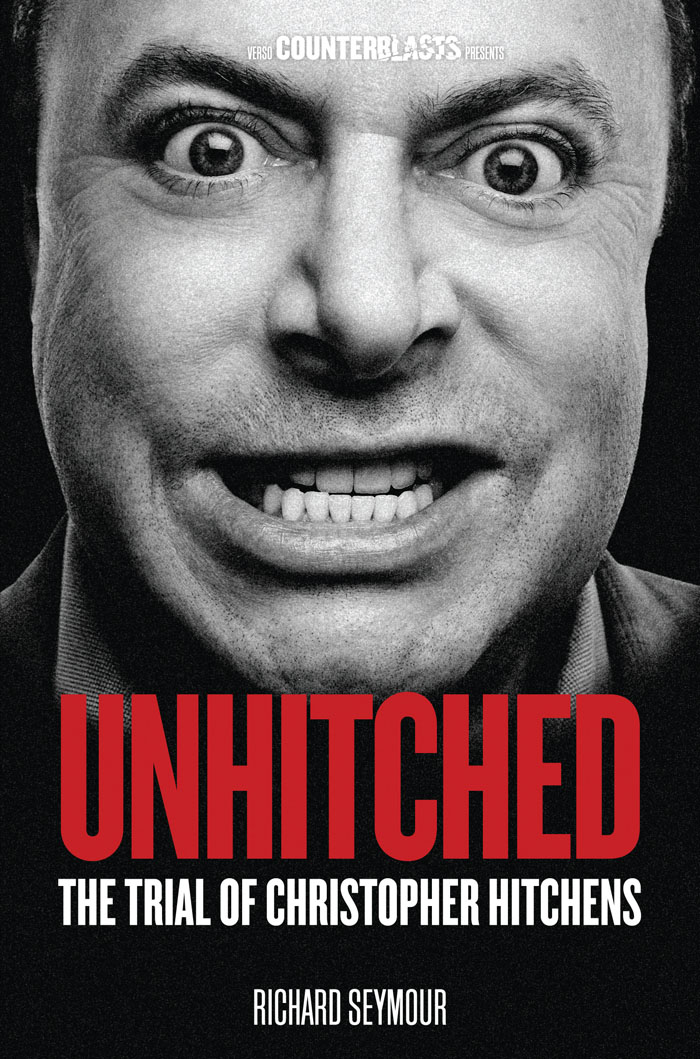

Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens, by Richard Seymour, Verso, 134pp, £9.99

Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens, by Richard Seymour, Verso, 134pp, £9.99

The secularists of the British Humanist Association launched a campaign last year to have a statue of the late Christopher Hitchens erected in Red Lion Square in central London. Although this proposal for a permanent tribute to the ex-leftist who evolved into an enthusiastic advocate of George W. Bush’s “War on Terror” came to nothing, it understandably generated fierce controversy at the time. Awale Olad, a Labour councillor in Holborn & Covent Garden who was approached by the BHA for his support, replied indignantly that he “would resign before I’d ever support the bust of a pro-war Islamophobe”.

This admirably forthright response wasn’t universally popular in the local Labour Party. Judging from letters in the Camden New Journal, opinion was split down the middle, with one prominent party member defending Hitchens as an honest humanitarian who supported the Iraq War for legitimate if mistaken reasons, and as an atheist who opposed religious beliefs in general and had no particular beef with Islam. It is a pity that Richard Seymour’s Unhitched had not been published then, as he does a very good job of demolishing both arguments.

A member of the International Socialists (forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party) in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Hitchens left the UK in 1981 to pursue a successful journalistic career in the USA, where his politics gradually shifted rightwards. Having lost any confidence in the labour movement as a vehicle for social change, he ended up embracing US imperialism as a force of historical progress. As Seymour shows, the offence was compounded by the dishonesty and double-talk with which Hitchens tried to justify his alliance with the warmongering Republican right.

With his best-selling book God Is Not Great, Hitchens ended his career in the company of “new atheists” like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris who have specialised in stoking anti-Muslim bigotry by depicting Islam as an existential threat to western civilisation. I have always wondered how Hitchens reconciled this with his early training in Marxism, which identifies the material basis of religious belief in oppression and alienation (“heart of a heartless world”, etc) and argues that the real struggle is against the social conditions that give rise to religion, not against religion as such. Seymour, however, makes a convincing case that Hitchens never agreed with, or even understood, the Marxist analysis of religion.

Unhitched has met with a number of hostile reviews from Hitchens’ supporters. Unable to answer Seymour’s actual arguments, they have resorted to ridiculing his supposedly pretentious style of writing. By this they mean that he occasionally uses long words that you wouldn’t normally hear in everyday conversation (the reference to one of Hitchens’ minor works as “opuscular” has occasioned great hilarity in such circles). All I can say is, if this is anyone’s idea of inpenetrable academic prose, they must have led an intellectually sheltered life.

This is a well written, clearly argued and thoroughly researched study. It is recommended reading for those – certain Camden Labour Party members in particular – who harbour the illusion that, by the time of his death in 2011, Hitchens retained any relationship at all with progressive politics.

First published in Labour Briefing in May 2013