Seymour Hersh and massacres — the degeneration of a respected journalist

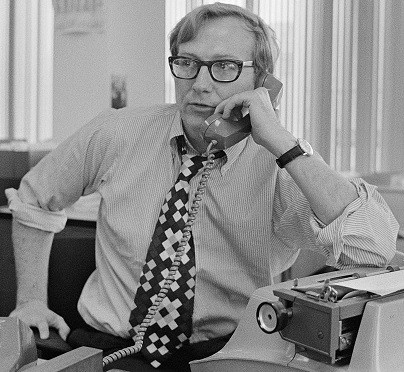

The celebrated investigative journalist Seymour Hersh appeared on the BBC Daily Politics show on Tuesday, mainly to plug his recently published book Reporter: A Memoir.

His interviewer Jo Coburn began the discussion by reminding us how Hersh established his name as a fearless and principled reporter through his exposure of the massacre of over five hundred Vietnamese civilians by US forces at My Lai in 1968. Then, depressingly, the discussion moved on to Hersh’s more recent role as a war-crime denier, apparently intent on trashing his own reputation by attempting to cover up the Assad regime’s horrific chemical weapons attacks on civilians in Syria.

Hersh’s ludicrous denial of regime responsibility for the sarin attacks carried out in Ghouta in August 2013, in which as many as 1,200 civilians may have been killed, and at Khan Shaykhun in April last year, where some 80 people died, unfortunately remained unexplored in the Daily Politics discussion. The reason for this was that Hersh evaded the issue.

Jo Coburn did ask him about a chemical weapons attack in Syria “last year”, which obviously referred to Khan Shaykhun. She pointed out that “a UN report concluded it was confident Damascus had used the nerve agent sarin” in that attack—which Hersh himself had denied in a story published by Die Welt a year ago. Coburn asked him: “Who are you to disagree with those conclusions?”

A good question. The OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism report from last October, to which Coburn was evidently referring, did indeed state unequivocally that it was “confident that the Syrian Arab Republic is responsible for the release of sarin at Khan Shaykhun on 4 April 2017”. Its findings demolished Hersh’s Die Welt story, in which he asserted that sarin had not been used at all. So it would have been interesting to see how Hersh justified his now debunked Die Welt piece. Perhaps understandably, as his position is indefensible, Hersh avoided answering Coburn’s question.

“Well, you’re not quite quoting it right”, he replied, referring to the report cited by Coburn. “There was a story in the New York Times that there was a section of the report that was deleted because of the lack of confidence.” But that New York Times article, titled “Horrific details on Syria chemical attacks left out, for now, from U.N. report”, had nothing to do with the OPCW-UN report on the Khan Shaykhun attack. The article was about another, entirely different report, commissioned by the UN Human Rights Council and published last week, on “The siege and recapture of eastern Ghouta”.

The New York Times revealed that a substantial section of the draft report (unofficially available here), which dealt with the Assad regime’s chemical attacks earlier this year on the then opposition-held town of Douma, had been omitted from the published version. The main reason for this appears to be that there is some remaining uncertainty over the notorious 7 April attack on a residential building in Douma, which killed some 49 civilians and provoked retaliatory airstrikes by the US, Britain and France against the Assad regime’s chemical weapons facilities. While the omitted draft section of the report gave a detailed account of the chlorine gas canister that struck the building after being dropped from a regime helicopter, it was unable to confirm suggestions made at the time by doctors treating the victims that a nerve agent had also been used in the attack.

The authors conceded that “it cannot be ruled out at this stage that another chemical agent was simultaneously employed”. But they continued: “A more likely alternative to the combined use of two chemical agents would be a massive chlorine release at a highly lethal concentration, triggering acute respiratory distress syndrome and near-immediate collapse.”

If no additional nerve agent was used, and the deaths were caused exclusively by what the draft report describes as an “improvised munition … based around a single industrial gas cylinder fitted to a metal frame or ‘cradle’, with affixed fins and wheel assemblies”, then the rationale for the US-UK-French strikes on the regime’s chemical weapons sites falls apart. It doesn’t require specialised facilities to produce a crudely modified gas cylinder of the type that was used in the 7 April Douma attack — so, contrary to the claims by the US and its allies, their airstrikes on those sites would have had no effect at all on the regime’s capacity to carry out further such attacks in future. It’s understandable that the UNHRC might want to withhold its provisional findings pending further investigation.

As far as Hersh is concerned, though, even the well-established fact that the building was hit by a chlorine missile is without substance. Having evaded Jo Coburn’s challenge to his discredited Khan Shaykhun story, he continued: “There was a story just the other day, again about the Assad regime dropping chemical bombs — chlorine bombs — and there’s no such thing as a chlorine bomb.” Despite interrogation by Coburn, Hersh continued to insist that “there’s no credible American intelligence report that suggests that Bashar Assad dropped chlorine bombs”.

Hersh’s claim has been taken apart by the ever-reliable Brian Whitaker. Writing on his al-bab.com blog, Whitaker notes that Hersh initially appeared to be making the technically correct, if rather pedantic and evasive, point that the chlorine missiles used by the Assad regime to attack opposition-held areas do not constitute bombs because they usually contain no explosives. However, as Whitaker points out, in his Daily Politics interview Hersh went further than this — he refused to admit that the regime had carried out any chlorine attacks at all. Hersh asserted that the deaths and injuries caused by chlorine inhalation, in Douma and elsewhere, were all the results of conventional bombing by government forces in which canisters of chlorine, which were stored in buildings for use in water purification, had been damaged in the attacks, accidentally releasing the potentially lethal gas.

(We might note in passing that Hersh’s thesis regarding the Douma attack contradicts another version of events, highly popular with Assad apologists, which was promoted at the time by Robert Fisk. Another once-respected journalist who has destroyed his reputation over Syria, Fisk arrived in Douma in April after it had fallen to the regime’s forces, along with a number of other western journalists. One of them, Seth Doane of CBS News, was able to interview witnesses to the attack and even located the missile used to deliver the chlorine. But all Fisk managed to find was a pro-regime doctor who hadn’t even treated the victims himself but assured Fisk that they had all been suffering from hypoxia — oxygen deficiency — due to dust inhalation, not from gas poisoning. A story that Fisk happily repeated for the edification of his readers.)

Regarding the story about the accidental release of chlorine through a conventional airstrike, Brian Whitaker observes that Hersh came out with similar nonsense last year in response to the sarin attack at Khan Shaykhun. Hersh claimed that the regime’s forces had “targeted a jihadist meeting site … using a Russian-supplied guided bomb equipped with conventional explosives”, which had created a “toxic cloud” from “fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods” stored in the building, causing “neurotoxic effects similar to those of sarin”. As already noted, this story was demolished by the OPCW-UN investigation which clearly established the regime’s use of sarin in the attack.

When he published his Khan Shaykhun story in Die Welt Hersh could, at least temporarily, rely on some initial lack of clarity over the precise details of the incident. But the regime’s chlorine attacks on the civilian populations of opposition-held territories are so well documented that even the most mindless Assad apologist struggles to deny them. If there is one indisputable feature of Assad’s genocidal war against the Sunni majority population of Syria, it is his forces’ systematic use of weaponised chlorine cylinders. They were used repeatedly during the regime’s bloody destruction of opposition-held east Aleppo in late 2016, and Human Rights Watch published photographs of some of them.

Having absolved the Assad regime of carrying out chlorine attacks, Hersh went on to make an equally ridiculous claim about the anti-Assad opposition forces. He told Jo Coburn: “As you know, in East Ghouta, the opposition, they were in a dead-end game … the people, ISIS, refused to let many of the civilians leave.” There were two flaws in that argument.

The first is that ISIS had no fighters in eastern Ghouta. The opposition forces there consisted of Jaysh al-Islam, which was built up with Saudi support as a Salafi counterweight to both jihadi and democratic-Islamist currents, and Faylaq al-Rahman, which is influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood and aligned with the Free Syrian Army. Tahrir al-Sham, which is the latest incarnation of former al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra, had a small presence in eastern Ghouta. ISIS had none at all. But it is doubtful whether Hersh even knows the difference between these organisations. This is a supposed expert on Syria who once referred to Ahrar al-Sham as Sharm al-Sharma. As his critics pointed out, Hersh appeared to be confusing the name of a major component of the anti-Assad opposition with that of a popular variety of kebab.

The second flaw in the story about opposition forces refusing to allow civilians to leave eastern Ghouta is that it has been refuted by the UNHRC. The origin of Hersh’s allegation lies in a New York Times article by Anne Barnard who quoted one UN official as claiming that rebel snipers were preventing people fleeing to regime-held territory. But the recent UNHRC report on “The siege and recapture of eastern Ghouta”, which can be downloaded here, states: “All civilians spoken to by the Commission denied that members of armed groups interfered with their ability to leave eastern Ghouta through the humanitarian corridors.” To be fair, Anne Barnard is an honest enough journalist to have acknowledged (see here and here) that the UNHRC report contradicted her earlier article. You might have thought an experienced investigative reporter like Hersh would have spotted that.

In the Daily Politics discussion Jo Coburg told Hersh “You sound like an apologist for Assad”. To which he replied “I just believe in facts”. However, as I have demonstrated above, when it comes to the crimes of Bashar al-Assad, facts are the last thing Hersh is interested in. In contrast to his younger self who courageously exposed the truth about US involvement in a massacre in Vietnam, he has now degenerated into a despicable old man who covers up for a genocidal regime that conducts massacres in Syria. We can only reflect with regret on the appalling decline of a once great journalist.

First published on Medium in June 2018