Labour and the ‘Jewish vote’ in Barnet

It was always a bit of a long shot that the Labour Party might be able to take the London Borough of Barnet from the Tories, given that Labour has never succeeded in gaining a majority on that council since the dawn of history (well, since the first elections to Barnet Council in 1964 anyway). But the fact that Labour failed to win the council in this month’s elections, and even got five fewer seats than it did in 2014, has been exploited by the Labour right to continue their never-ending campaign against Jeremy Corbyn.

It was always a bit of a long shot that the Labour Party might be able to take the London Borough of Barnet from the Tories, given that Labour has never succeeded in gaining a majority on that council since the dawn of history (well, since the first elections to Barnet Council in 1964 anyway). But the fact that Labour failed to win the council in this month’s elections, and even got five fewer seats than it did in 2014, has been exploited by the Labour right to continue their never-ending campaign against Jeremy Corbyn.

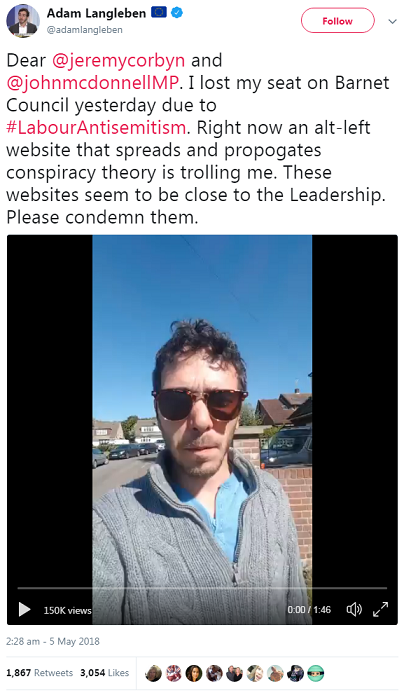

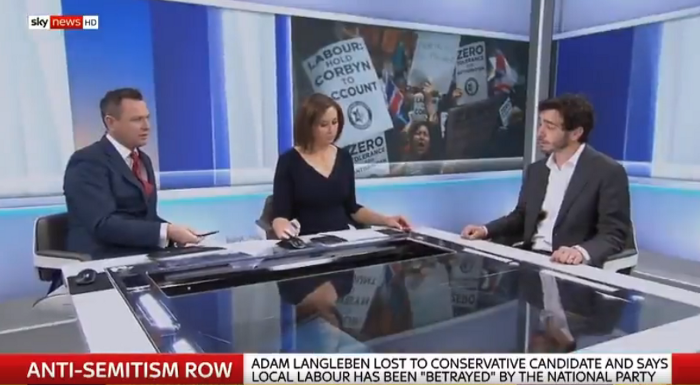

One of the ousted Labour councillors, Adam Langleben, spent several days touring the television and radio studios, and writing articles for the Huffington Post, the New Statesman and the Daily Mirror, angrily complaining that Labour’s “crisis of antisemitism” had repelled Jewish voters in Barnet and resulted in the party’s (and perhaps more importantly, his own) defeat.

A number of his critics have pointed to the irony that, as a leading member of the belligerently pro-Israel Jewish Labour Movement (formerly Poale Zion), Langleben has played a significant role in inciting the very hysteria over antisemitism that he now claims lost him his seat. If it really was the case that Labour’s Jewish voters deserted the party in droves in Barnet because they had been told the party is plagued by antisemitism, then it could be argued that Langleben was the architect of his own downfall. (Best not mention this to Adam, though. As you can see from this Twitter exchange, he gets a bit tetchy when his political opponents make that point.)

But does Langleben’s analysis (if we can dignify his largely evidence-free diatribes with that term) really hold up? Does Corbyn’s failure to drain the “cesspit of antisemitism”, to which the Labour Party has supposedly been reduced under his leadership, explain why Labour didn’t do better in Barnet? To answer that question, we need to look at the historical background to the Labour Party’s electoral relationship with the Jewish community.

It is generally assumed, admittedly on the basis of anecdotal evidence, that in the immediate post-war period a majority of Jewish voters backed Labour. (A 1947 Survey of Jewish Interests, which found that a third of Jewish respondents classed themselves as Labour or Socialist, another third as Liberals and one-fifth as Conservatives, was not necessarily reliable.) By the beginning of the 1980s, however, commentators were already noting a switch of Jewish political support to the Tories. While analysts differed over whether there was a “link between the swing to the right and the Israel-Zionist vote”, there was agreement that the rising affluence of the Jewish community was the fundamental factor in weakening allegiance to Labour. (We might observe in passing that when Ken Livingstone made that same uncontroversial point in 2012, he was pilloried by Zionists who accused him of appealing to the antisemitic stereotype of “rich Jews”.)

As Geoffrey Alderman wrote in London Jewry and London Politics, 1889–1986 (1989), pp.137–8:

“During the 1980s the close relationship of former times between London Jewry and the Labour Party finally fell apart. In moving out from east London into the suburbs the Jews had also moved up, into the ranks of the middle classes. Even in the early 1960s a survey of Jews in Edgware (within the Borough of Barnet) had revealed that over 80 per cent of the sample regarded themselves as middle-class. An analysis of Redbridge Jewry, carried out by the Board of Deputies in 1978, showed that 70 per cent of the Jews there belonged to the professional, managerial, and skilled non-manual occupational classes. These were precisely the groups among which the Conservative Party that Mrs Thatcher led from 1975 was to make some of its most eager converts.”

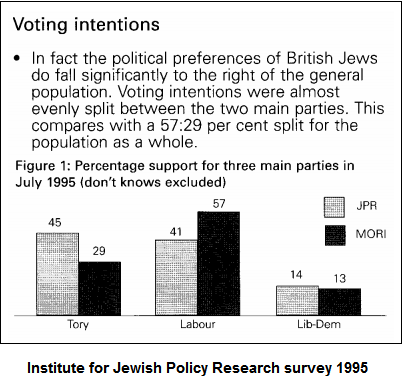

When it comes to analysing the transfer of Jewish political allegiance to the Tories, we lack the statistical evidence that would enable us to quantify or periodise that development. It wasn’t until 1995 that the first major survey of Jewish voters was conducted, by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research. It showed that, in contrast to the deep disaffection with John Major’s government then prevailing among the general population, which would result in Tony Blair’s landslide general election victory two years later, Conservative support among Jewish voters remained high, with 45% backing the Tories and only 41% Labour (excluding don’t knows). JPR followed earlier commentators in attributing the rightward-leaning politics of Jewish voters to “the proportion of British Jews in middle class, professional occupations” (while also noting that Jews were politically to the left of non-Jews of equivalent socioeconomic status).

When it comes to analysing the transfer of Jewish political allegiance to the Tories, we lack the statistical evidence that would enable us to quantify or periodise that development. It wasn’t until 1995 that the first major survey of Jewish voters was conducted, by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research. It showed that, in contrast to the deep disaffection with John Major’s government then prevailing among the general population, which would result in Tony Blair’s landslide general election victory two years later, Conservative support among Jewish voters remained high, with 45% backing the Tories and only 41% Labour (excluding don’t knows). JPR followed earlier commentators in attributing the rightward-leaning politics of Jewish voters to “the proportion of British Jews in middle class, professional occupations” (while also noting that Jews were politically to the left of non-Jews of equivalent socioeconomic status).

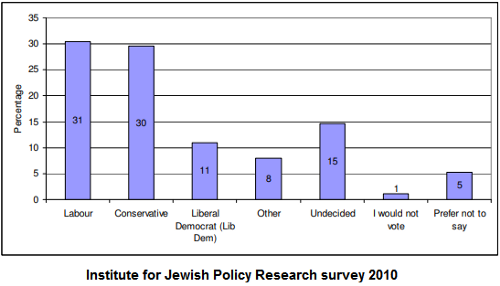

Under Blair’s leadership it appears that Jewish support for Labour did recover slightly. No doubt Blair’s enthusiastic and almost entirely uncritical support for the actions of the state of Israel — most flagrantly during the 2006 war on Lebanon — was a factor here. When JPR conducted its next survey of Jewish voters in 2010, it found that Labour had a slight lead, with 31% of respondents supporting the Labour Party compared with 30% who backed the Tories.

Under Blair’s leadership it appears that Jewish support for Labour did recover slightly. No doubt Blair’s enthusiastic and almost entirely uncritical support for the actions of the state of Israel — most flagrantly during the 2006 war on Lebanon — was a factor here. When JPR conducted its next survey of Jewish voters in 2010, it found that Labour had a slight lead, with 31% of respondents supporting the Labour Party compared with 30% who backed the Tories.

By 2017, though, support for Labour in the Jewish community had fallen disastrously. A Survation poll for the Jewish Chronicle in May that year revealed that only 11.8% of Jewish voters intended to back Labour in the forthcoming general election, while 67.7% said they were going to vote Tory. Yet the same poll showed that only 14.2% of respondents had voted Labour in the 2015 general election. In other words, contrary to popular myth and claims by the anti-Corbyn media, it was under Ed Miliband’s leadership, rather than Jeremy Corbyn’s, that the collapse of Labour’s Jewish vote took place.

What led to Labour losing over half of its Jewish supporters between 2010 and 2015? The explanation lies in Miliband’s adoption of a much more pro-Palestinian stance than previous Labour leaders. In 2014, during the war on Gaza, he attacked David Cameron over his “silence on the killing of hundreds of innocent Palestinian civilians caused by Israel’s military action”. He followed that up by facing down objections by pro-Israel Labour MPs in order to back a Commons motion in favour of recognising Palestine as an independent state. None of that would have happened under Blair or Gordon Brown. It provoked warnings that Jewish donors would withdraw financial backing from Labour over Miliband’s “toxic” stance on Israel. On a more trivial level, Maureen Lipman received widespread media coverage when she announced that she was ending five decades of support for the Labour Party over Miliband’s actions. (This didn’t prevent her from doing the same again this year in protest against Corbyn.)

Not that Miliband was any opponent of Zionism. When asked at a Board of Deputies event in 2013 whether he was a Zionist, his reply was: “Yes, I consider myself a supporter of Israel.” After his return from an official visit to Israel in the spring of 2014 he addressed Labour Friends of Israel, expressing enthusiastic support for the Zionist state and declaring his commitment to “working with LFI to further deepen the relationship between my party and the Israeli Labour Party led by Isaac Herzog”. (Yes, that would be this Isaac Herzog.) During the Gaza war Miliband balanced his criticisms of Israel by denouncing Hamas as “an appalling, terrorist organisation” and emphasising his support for Israel’s right to self-defence. But this just wasn’t good enough for the Zionist establishment. Nothing short of unconditional support for Israel would do.

The London Evening Standard ran a piece on the eve of the 2015 general election (“Thatcher’s seat is not for turning as Jewish voters warn Labour over Israel”) reporting that Labour would have difficulty winning back the Finchley & Golders Green seat in Barnet — which Labour MP Rudy Vis had represented from 1997 to 2010 — because of opposition to Labour on the part of the constituency’s Jewish population. The Board of Deputies’ Jonathan Arkush was quoted as saying, quite explicitly, that it was “Labour’s hostile stance towards the state of Israel” that was turning Jewish voters away from Labour. Arkush made no mention at all of raging antisemitism within the Labour Party being a factor in the loss of Jewish support. That fairytale had yet to be invented.

The Standard’s prediction that Labour would fail to win Finchley & Golders Green proved to be accurate. The Tories held the seat quite easily in 2015, getting 50.9% of the vote with Labour finishing well behind on 39.7%. However, in 2017 under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership the result was much closer, with the Tories on 47% and Labour on 43.8%. The same picture presented itself in the neighbouring Barnet constituency of Hendon, where the Tories held the seat in 2015 with 49% of the vote as against Labour’s 41.5%, but only by 48% to 46% in 2017.

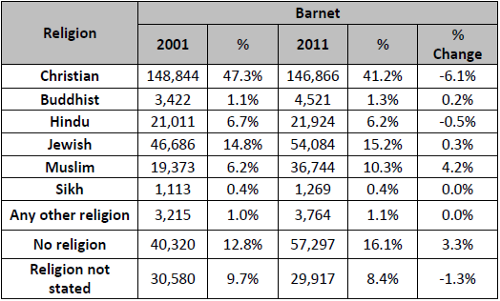

It is highly unlikely that these improved results were due to a shift back to Labour among Jewish voters. As we have seen, Jewish support for Labour was even lower in 2017 than it was in 2015 — in London it was down from 16.2% to 12.1% — and there is no reason to suppose that Barnet bucked the trend. Yet this didn’t prevent Labour from coming close to winning the two seats. The explanation is that Jewish voters are nowhere near a majority or even a numerically decisive minority in Barnet, forming just 15.2% of the borough’s population. It is true that Finchley & Golders Green and Hendon are the two parliamentary constituencies with the highest proportion of Jewish voters in the UK, but they make up no more than 21.1% of the electorate in the former and 17% in the latter.

The reality is that Barnet is becoming an increasingly diverse borough, with Muslims forming the largest non-Jewish minority, officially making up 10.3% of the population. That figure is from the 2011 census, and given that the Muslim population was expanding rapidly at the time (it was up from 6.2% in 2001), whereas the Jewish population had remained almost static, it wouldn’t be surprising if the number of Muslim voters in Barnet today is approaching that of Jewish voters.

The reality is that Barnet is becoming an increasingly diverse borough, with Muslims forming the largest non-Jewish minority, officially making up 10.3% of the population. That figure is from the 2011 census, and given that the Muslim population was expanding rapidly at the time (it was up from 6.2% in 2001), whereas the Jewish population had remained almost static, it wouldn’t be surprising if the number of Muslim voters in Barnet today is approaching that of Jewish voters.

As such Muslims are as capable of influencing the outcome of elections in Barnet as the Jewish community, although you wouldn’t know that from listening to Labour right-wingers and media commentators. A case in point was Labour’s loss in 2010 of the Hendon parliamentary seat, which it had held since 1997. This defeat certainly wasn’t due to the sitting MP Andrew Dismore failing to appeal to the pro-Israel majority of the Jewish electorate. There was no atrocity committed by the Zionist state against the Palestinian people that Dismore wouldn’t try and justify. And this was what lost him his seat. An activist group named the Muslim Public Affairs Committee organised an energetic and high-profile intervention against Dismore in the 2010 general election, calling on Muslim voters to reject him because of his position on the Israel-Palestine conflict. They argued, persuasively, that his hardline Zionist stance showed contempt for the pro-Palestinian sympathies of his Muslim constituents. Dismore lost to the Tory candidate by just 106 votes, and MPACUK not unreasonably claimed that their campaign had ensured his defeat.

Moreover, as we have already noted, by 2015 Labour’s support among Jewish voters had been reduced to 14.2% nationally, while in London the figure was only slightly higher at 16.2%. Given that the Jewish community made up 15.2% of the population in Barnet, as of 2015 Jewish Labour voters would have constituted around 2.5% of the borough’s electorate. Even if every one of these voters had subsequently deserted Labour in response to the moral panic over antisemitism in the party, the overall impact on the results of the 2018 council elections would have been negligible.

It is true that the Jewish population of Barnet is unevenly spread across the borough, being heavily concentrated in a handful of wards. In Garden Suburb 38% of the electorate is Jewish, in Golders Green the figure is 37% and in Edgware 33%, while Finchley Church End and Hendon both have a Jewish populations of 31%. Obviously the Jewish community could potentially play an electorally influential role in these particular wards. However, in reality, they are situated in the more affluent areas of Barnet and consequently are solidly Tory, having consistently elected Conservative candidates for decades. So any defection of Labour’s Jewish voters in these five wards would have no effect whatsoever on the composition of Barnet Council.

An academic named Daniel Allington has attempted to give some substance to the view that Labour was defeated in Barnet because of a Jewish revolt against “vile antisemitism” in the party, by producing a graph which purports to show that “Labour picked up votes only in those parts of Barnet where the Jewish population was low; the more Jews there were within a ward, the more likely it was to lose them instead”. Adam Langleben was predictably impressed with these findings, as was Dave Hill of On London, who wrote admiringly that Allington’s analysis “will take some refuting”.

But correlation does not imply causation. The Barnet wards in which there is a heavy concentration of Jewish voters are also characterised by greater affluence and majority support for the Tories, as previously noted, while wards with a lower proportion of Jewish voters tend to be more economically deprived and strongly Labour-voting. The pattern identified by Allington could just as well be explained by well-off Tory supporters being motivated to turn out in greater numbers in order to oppose a Labour Party whose national leader they see as a dangerous left-wing extremist, thus depressing Labour’s share of the vote in the wards that also happen to have large Jewish populations.

In any case, as you can see from the distribution of red dots on the graph, Allington’s analysis is an oversimplification of a complex situation. Take Golders Green, which as we have seen is one of the two Barnet wards with the highest proportion of Jewish voters. Here Labour’s candidates gained an additional six hundred votes compared with 2014, and while the Tories picked up even more votes, Labour’s percentage share of the total was only slightly down on four years ago. Not much of a Jewish voters’ revolt there, it would seem. On the other hand, in the neighbouring Garden Suburb ward, which has a similarly high proportion of Jewish voters, the result was more in line with Allington’s analysis, with Labour suffering heavy losses. We’re invited to believe that the driving force behind the latter result was outrage by Jewish voters at stories of Labour antisemitism, yet just across the border in Golders Green ward their co-religionists (who include a large number of non-Zionist strictly Orthodox Jews) were apparently far less exercised by the issue.

Playing down the importance of a generalised revolt against Labour by Jewish voters, the Jewish Chronicle argued that the “the vast majority of wards showed results that had been expected”, but that the crucial impact of the Jewish vote was felt in Hale and West Hendon where, despite the “strong Jewish Labour traditions” in these wards, voters “defected from Mr Corbyn’s Party — either voting Conservative or not voting at all”. In an article for the Daily Mirror the JC’s political editor Lee Harpin repeated this argument: “Look closely at the voting patterns and in two key wards in the borough — Hale and West Hendon — both of which had long been Labour strongholds, and you discover they were lost to the Tories because relatively small numbers of Jewish Labour supporters in each area decided en masse to boycott the party.”

As far as the Hale ward is concerned, it is psephological nonsense to describe it as having long been a Labour stronghold. Over the years Hale has returned Tory councillors more often than Labour. The exceptions were in 1994 when Labour won one of the three seats; in 1998 and 2002 when Labour won two seats, before losing both of them in 2006; and in 2014 when Labour narrowly won one seat, with their successful candidate finishing just 9 votes ahead of the defeated Tory. Although Labour lost that seat in 2018, the result showed a significant increase in the Labour vote in Hale compared with 2014, up from 5,883 to 6,489. The problem was that the Tory vote went up even more, from 6,343 to 9,136. Overall turnout rose dramatically as a consequence, from 13,637 to 17,103, and Labour’s percentage share of the total vote was down on 2014.

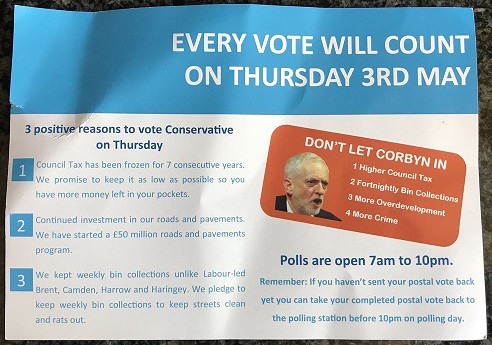

It’s difficult to know what to make of this result. Given that six hundred more voters backed Labour than in 2014, it doesn’t provide much support for the assertion that former Labour voters boycotted the party by backing the Tories or staying at home. As suggested earlier, a possible explanation could be that Tory voters, alarmed at the prospect of a Corbyn-led Labour Party taking control of Barnet Council, turned out in large numbers to prevent that happening. This is not to deny that the collapse of Labour’s support within the Jewish community since the last borough elections may have been a contributory factor. After all, those elections took place in May 2014 before Ed Miliband had alienated Zionists with his progressive positions on the Gaza war and Palestinian statehood. Without further research, the exact weight to be attached to the role of Jewish voters, who make up 19% of the electorate in Hale, is unclear. But it’s very unlikely to be the sole explanation for such a big increase in the Tory vote.

It’s difficult to know what to make of this result. Given that six hundred more voters backed Labour than in 2014, it doesn’t provide much support for the assertion that former Labour voters boycotted the party by backing the Tories or staying at home. As suggested earlier, a possible explanation could be that Tory voters, alarmed at the prospect of a Corbyn-led Labour Party taking control of Barnet Council, turned out in large numbers to prevent that happening. This is not to deny that the collapse of Labour’s support within the Jewish community since the last borough elections may have been a contributory factor. After all, those elections took place in May 2014 before Ed Miliband had alienated Zionists with his progressive positions on the Gaza war and Palestinian statehood. Without further research, the exact weight to be attached to the role of Jewish voters, who make up 19% of the electorate in Hale, is unclear. But it’s very unlikely to be the sole explanation for such a big increase in the Tory vote.

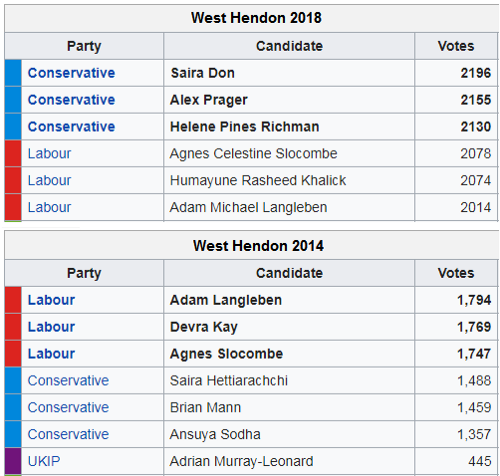

West Hendon, by contrast, has indeed traditionally been a Labour-held ward, although the Tories have generally got a substantial vote there. In 2010 they ran Labour quite close, with the best-placed Tory candidate receiving just 60 fewer votes than the worst-placed Labour candidate (2,293 votes as against 2,353). And this was at a time when Jewish support for Labour was on a par with that for the Tories. As in Hale, the Labour vote in West Hendon increased significantly in 2018, with its candidates receiving 6,166 votes as against 5,310 in 2014. But the Tory vote went up more, from 4,304 to 6,481, which allowed them to take all three seats, including Adam Langleben’s. Overall turnout rose from 11,456 to 13,632. So the picture here is similar to Hale, although in West Hendon the growth in the Tory vote and turnout was less dramatic, and Labour’s share of the total vote was only slightly down on 2014.

It is notable that whereas Langleben topped the poll in West Hendon in 2014, this time he finished last of the three Labour candidates. The other two Labour candidates were 52 and 56 votes behind the third-placed Tory candidate, while Langleben was 116 votes adrift. If Labour’s loss of West Hendon was due to Jewish voters punishing the party over accusations of antisemitism, it’s not immediately obvious why Langleben should have done significantly worse than the other two Labour candidates, neither of whom is Jewish. Obviously there was more going on here than a protest by angry Jewish voters.

It is notable that whereas Langleben topped the poll in West Hendon in 2014, this time he finished last of the three Labour candidates. The other two Labour candidates were 52 and 56 votes behind the third-placed Tory candidate, while Langleben was 116 votes adrift. If Labour’s loss of West Hendon was due to Jewish voters punishing the party over accusations of antisemitism, it’s not immediately obvious why Langleben should have done significantly worse than the other two Labour candidates, neither of whom is Jewish. Obviously there was more going on here than a protest by angry Jewish voters.

It is possible that the Muslim voters of West Hendon — who make up 17% of the electorate, outnumbering the 14% of Jewish voters — could have had a hand in this. To be fair, Langleben did have a record of opposing the Islamophobia whipped up by a section of the Jewish community in response to Golders Green Hippodrome’s conversion into a Shia community centre. But his reputation as a militant Zionist who spends his time banging on about the Labour Party being riddled with antisemitism, and angrily demanding the expulsion of Ken Livingstone for “Holocaust revisionism”, would not have endeared him to his Muslim constituents. Nor would Langleben’s widely publicised campaign to rid the local Labour Party of a Muslim member named Laura Stuart, on the basis of accusations of antisemitism for which he was unable to provide adequate proof.

There is also the UKIP factor to be taken into consideration. In 2014 UKIP stood one candidate in West Hendon, winning 445 votes, but they did not contest the ward again this year. The UKIP supporters from 2014 presumably transferred for the most part to the Tories. Given that the difference between the Tory vote and the Labour vote in West Hendon was only 315 (6,481 as against 6,166) it looks as though former UKIP voters may possibly have tipped the balance in favour of a Tory victory.

Because Jews make up only a small minority of the electorate, whether in Barnet as a whole (15%) or in Hale and West Hendon (19% and 14% respectively), promoters of the view that the antisemitism crisis destroyed Labour’s chances in Barnet struggle to justify that claim. Even Jewish Chronicle editor Stephen Pollard conceded that, given the relatively low numbers of Jewish voters in the borough, they were “not enough on their own” to have inflicted an electoral defeat on Labour in protest at the party’s supposed softness on antisemitism. However, Pollard had the answer to this conundrum: “Crucially, many non-Jews joined the protest”, because they “simply would not accept Labour’s toleration of Jew hate”. Needless to say, Pollard was unable to put any numbers on these non-Jews who had participated in the protest vote, or indeed to provide any evidence at all that they had done so.

In fact the evidence we do have indicates that the general public has maintained a healthy degree of scepticism in response to the barrage of propaganda about Labour’s antisemitism crisis. Last month BMG conducted a survey for the Independent in which respondents were asked whether they thought the main political parties had a problem with racism and/or religious prejudice. The headline to the report in the Independent read: “Antisemitism: Two-thirds of Britons think Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour has problem with prejudice, poll reveals”. But this was misleading.

The details of the poll are available here. BMG found that 27% of respondents didn’t know whether Labour has a problem with racism or religious prejudice, while 12% said that the party has “no problem at all”. The figure for those who thought Labour does have some sort of problem was 61%, not two-thirds. This was made up of 21% who thought Labour has only a “small/limited problem”, and a further 21% who thought it has “somewhat of a problem”, while those who said Labour has a “considerable problem” amounted to just 19%. The latter figure is astonishingly low, given that you can hardly turn on the TV and radio or pick up a newspaper these days without being assailed by shock-horror stories about Labour suffering from an antisemitism problem of catastrophic proportions.

The BMG/Independent poll found that even fewer Labour supporters bought into the crisis-of-antisemitism narrative. Just 7% of respondents who voted Labour in 2017 thought the party has a “considerable problem” with racism and religious prejudice, while only 5% of those intending to vote Labour in the next general election took that view — which suggests that Labour hasn’t lost many of its supporters due to the media hysteria over antisemitism. By contrast, 40% of intending Tory voters thought Labour has a considerable problem with racism or religious prejudice, as did 37% of respondents who intended to vote for UKIP, the party with by far the worst record when it comes to racial and religious bigotry. It’s not hard to work out that many of the 19% of the population who accept the propaganda that Labour is wracked by antisemitism are not moved by progressive opposition to racism but by right-wing hostility to the Labour Party.

These findings are in obvious contradiction to Stephen Pollard’s line — also promoted by Barnet Labour group leader Barry Rawlings, politically disoriented “left-wing” media commentator Owen Jones and, unsurprisingly, Adam Langleben — that a Jewish protest vote against Labour was boosted by large numbers of sympathetic anti-racists from outside the Jewish community, who expressed solidarity with their Jewish friends and neighbours by indignantly rejecting Labour candidates because of the party’s record on antisemitism.

For reasons outlined above, the assertion by the likes of Langleben that antisemitism was “the only explanation” for Labour’s failure to take Barnet Council doesn’t hold up. In the absence of any in-depth survey we can only speculate, but Labour’s setback in Barnet would appear to be due to a combination of factors. This was a highly polarised political situation, in which Labour was seen to be in with a chance of taking control of the council, resulting in a much higher turnout in some wards, with Labour and Tory voters going to the polls in increased numbers, which led to a rise in the percentage share of the vote for both parties. The problem was that the Tory Party’s supporters were evidently more highly motivated to go out and vote than Labour’s were.

Would it be too much to suggest that Barnet Labour Party’s leaders themselves bore some responsibility for their failure to inspire Labour voters? One admittedly politically hostile critic, who predicted months ago that Labour would fail to win Barnet, put it down to the party’s local leadership being “chaotic and useless”. And while the antisemitism issue was seized on by the Tories in order to divert attention from their own record governing the borough, it didn’t exactly help to focus voters’ minds on local policy issues when you had the leader of Barnet Labour group and other councillors joining in the attacks on Jeremy Corbyn over that same diversionary issue.

Unfortunately, Labour’s national leadership appears unwilling to consider such alternative explanations. When Adam Langleben tweeted a video he’d made featuring a lying attack on the pro-Corbyn Skwawkbox blog, which he falsely accused of “propagating Labour antisemitism”, shadow chancellor John McDonnell responded by expressing his sympathy for Langleben and agreeing to meet him to discuss the Barnet result, along with Langleben’s fellow ousted Labour councillor Phil Cohen.

Unfortunately, Labour’s national leadership appears unwilling to consider such alternative explanations. When Adam Langleben tweeted a video he’d made featuring a lying attack on the pro-Corbyn Skwawkbox blog, which he falsely accused of “propagating Labour antisemitism”, shadow chancellor John McDonnell responded by expressing his sympathy for Langleben and agreeing to meet him to discuss the Barnet result, along with Langleben’s fellow ousted Labour councillor Phil Cohen.

Did McDonnell take the opportunity to ask Cohen how his own political defeat in a ward where just 5% of the electorate is Jewish—he was the only Labour candidate in previously all-Labour East Barnet to lose to a Tory, having received over a hundred fewer votes than the other two Labour candidates — was compatible with the claim that Labour’s reverses in Barnet were all down to a revolt against antisemitism? I doubt that figured in the discussion. If we accept Langleben’s account of the meeting as accurate — a bit of a stretch I grant you — McDonnell “admitted the Labour defeat in Barnet was a result of the anti-Semitism scandal that had recently dogged the party”.

But this is par for the course with the Labour leadership. When the witch-hunt over antisemitism kicked off, they decided (with the admirable exception of Diane Abbott) to take the road of appeasement, caving in to the Zionist lobby and its allies in the Tory Party and Labour right. When McDonnell’s then PPS Naz Shah came under attack two years ago, his response was to throw her under the bus. When Ken Livingstone stepped forward to defend Shah, he too was sacrificed. More recently we’ve had shadow attorney general Shami Chakrabarti joining with massacre-supporting Board of Deputies president-elect Marie van der Zyl in demanding Ken’s expulsion from the party. Ken’s own tactics may not be entirely flawless, but his basic strategic conception is correct. Namely: there’s no point making concessions to your attackers, because it will only encourage them to come back for more; better to stand your ground and defy the bastards. There’s still time for the Labour leadership to change course, grow a political backbone and tell Zionist malcontents like Adam Langleben (if I may borrow his own preferred polemical terminology) to fuck off.

First published on Medium in May 2018