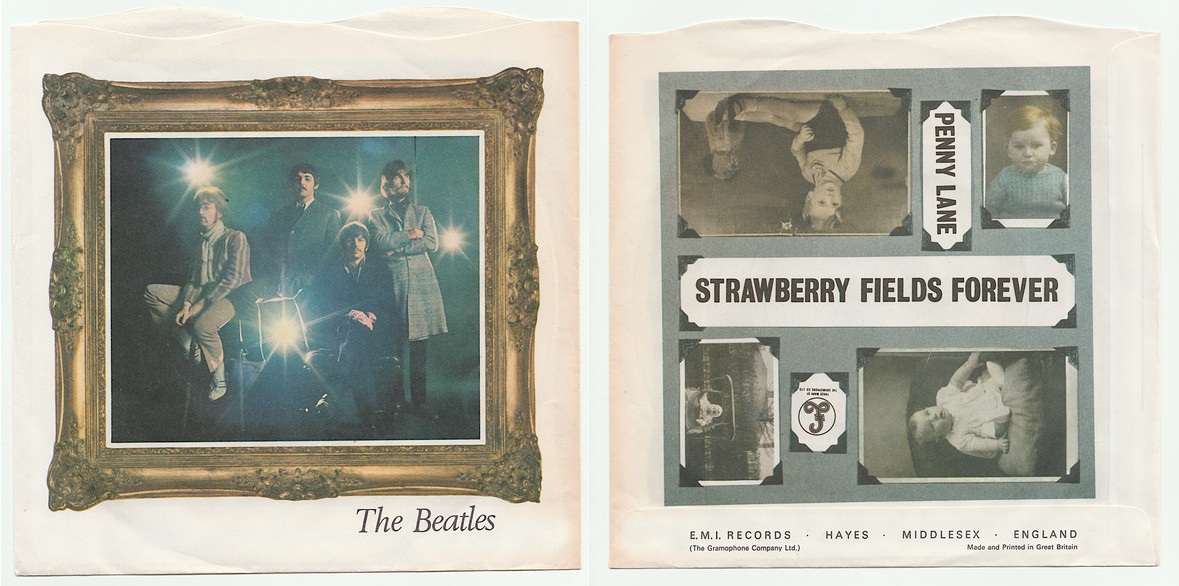

Why did Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields fail to top the charts in 1967?

There are Beatles fans who still harbour resentment over the fact that back in 1967 the group’s double A-sided single Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields Forever only reached #2 in the charts. It was certainly a shock at the time. In his memoir Summer of Love: The Making of Sgt Pepper George Martin observed that after a run of twelve consecutive number ones the phenomenon of Beatles singles topping the charts “had become as reliable as the sun coming up — and we took it almost as much for granted. Alas, with unlucky number thirteen, it was not to be”.

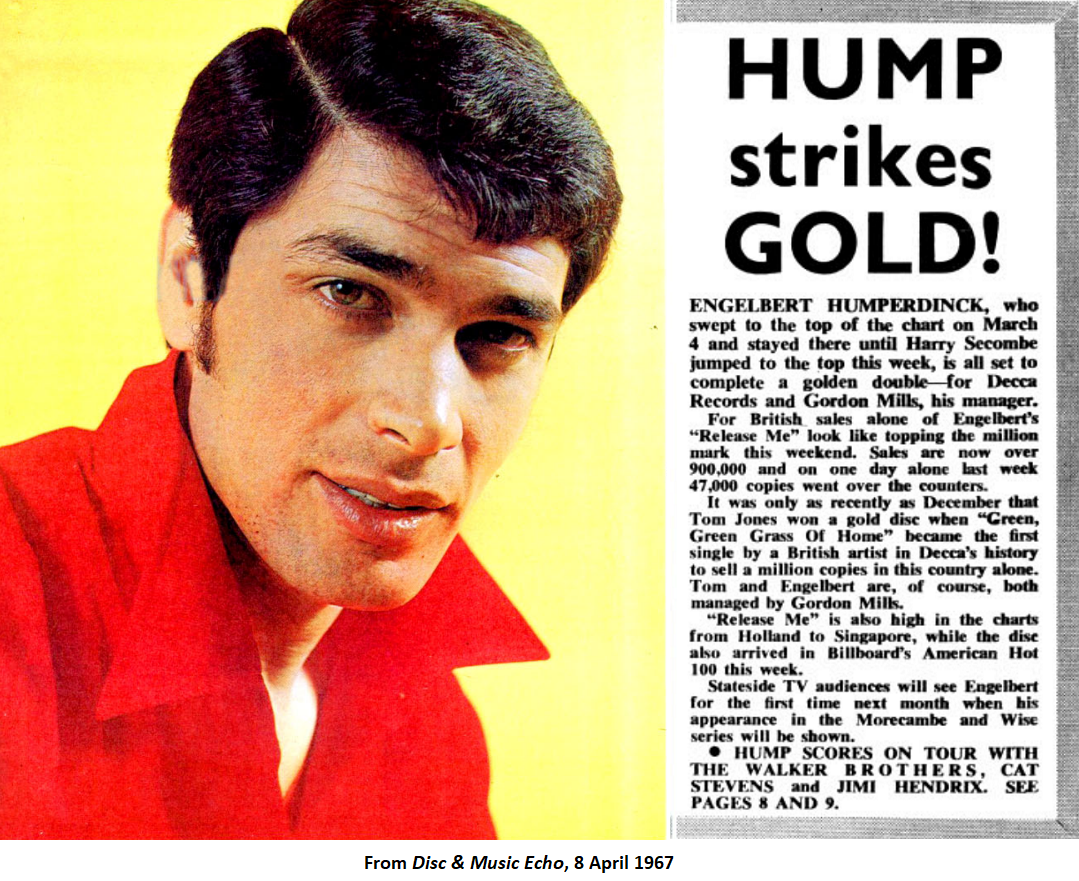

To add insult to injury the Beatles’ masterpiece was kept off the #1 spot by the lachrymose ballad Release Me, recorded by one Arnold George Dorsey under the much-ridiculed pseudonym Engelbert Humperdinck (the name of a nineteenth-century classical composer best known for his opera Hansel and Gretel). How, admirers of the Beatles not unreasonably demand, could this anodyne piece of pap possibly have outranked the group’s greatest ever single in its appeal to British record-buyers?

Some Beatles fans insist that it didn’t. They point to a garbled account of the record’s chart performance in the Wikipedia entry on Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields, which states that it “sold considerably more” than Release Me. In support of this claim Wikipedia cites a Billboard article arguing that Engelbert won the competition for the top spot “despite the Fab Four selling nearly twice as many records”. But the argument doesn’t stack up. With sales of 1.38 million in the UK, Release Me was one of the most commercially successful singles of the 1960s. If Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields had shifted nearly twice as many copies it would have sold around 2.7 million! No Beatles record ever came close to that.

In 2010 the Official Charts Company compiled a list of the sixty best-selling singles of the 1960s for BBC Radio 2. Unsurprisingly, records by the Beatles held five of the top ten positions. These were She Loves You (#1) and I Want To Hold Your Hand (#2) from 1963, Can’t Buy Me Love (#4) and I Feel Fine (#5) from 1964, and We Can Work It Out/Day Tripper (#7) from 1965. But the Beatles singles that were issued in 1967 did less well. Hello, Goodbye rated the highest of these at #21 on the OCC list, with All You Need Is Love at #34 and Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields at a lowly #51. At #8 on the list Release Me outsold all three of them. Although it may pain some Beatles fans to admit it, I don’t think there’s any doubt that Release Me sold more copies than Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields, and this is the straightforward reason why it kept the latter off the top spot on the charts.

Additional and more authoritative backing for the “we wuz robbed” school of thought is provided by George Martin. In his 1979 book All You Need Is Ears, Martin was still expressing puzzlement over the record’s disappointing showing: “To this day I cannot imagine why that single was beaten to the number one spot, because for my money it was the best we ever issued.” By 1994 he had come up with an explanation which he presented in his book on the making of Sgt Pepper. Describing the decision to issue Penny Lane/ Strawberry Fields as a double A-side as “the biggest mistake of my professional life”, Martin continued:

“The all-important music charts were run by the three music papers:: Melody Maker, New Musical Express, and Record Mirror. These rival charts were compiled from a fairly crude system of record retailer reports, submitted by different outlets each week. If I had stopped to think for more than about a second, I would have realized that one great title would fight another; and this is exactly what happened. The reports came in, and they showed that our double-A-side was selling extremely well. There was only one problem. The weekly sales figures showed that two singles, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and ‘Penny Lane’, were selling well. They were being counted separately! As far as the charts were concerned, one side was effectively cancelling out the success of the other. I firmly believe that if the total sales of those two sides had been added together we would have squashed the opposition flat.”

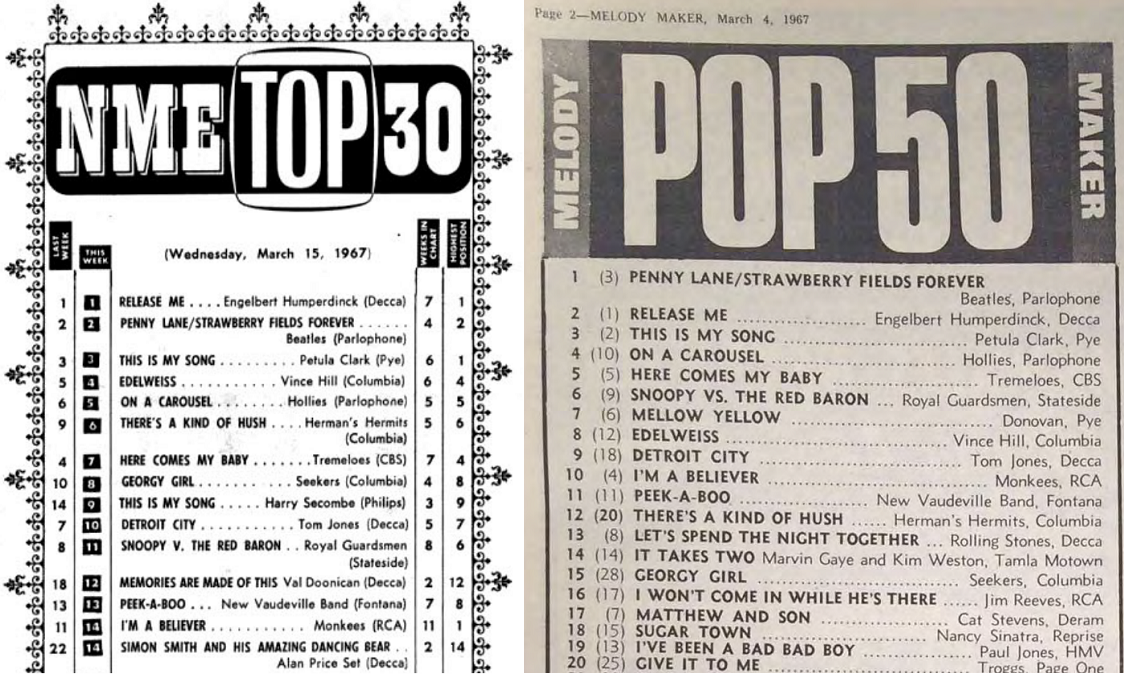

I think George Martin was mistaken on this point. (As on others — he misremembered the contents of the acetates Brian Epstein brought to his office in 1962, and recalled the Beach Boys following up Pet Sounds with “another corker” of an album titled Good Vibrations.) His error is perhaps understandable, given the confusion resulting from the numerous charts that co-existed in the UK up until 1969, when the BBC and music trade publication Record Retailer jointly commissioned the British Market Research Bureau to compile one official chart. In 1967 there were in fact four music papers — the NME, Melody Maker, Disc & Music Echo and Record Retailer — who each compiled their own chart (Record Mirror used the Record Retailer version). A fifth chart was produced by the BBC, based on an average of those four.

Of the five charts, it was the NME’s that sometimes adopted a policy of calculating double A-sides as separate entries, which did have the effect of lowering the chart placing of each song. For example, the two sides of the Yardbirds’ 1965 single Evil Hearted You/Still I’m Sad charted at #10 and #9 respectively with the NME, although the record reached #3 on the Record Retailer chart. But the NME followed the other charts in treating the Beatles’ double A-sides as a single entry. They had done so with We Can Work It Out/Day Tripper in 1965 and Eleanor Rigby/Yellow Submarine in 1966, and continued the practice with Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields. So George Martin’s argument doesn’t appear to have any basis in fact.

Because they used returns from different record shops, the music papers obviously produced slightly different charts. Record Retailer, the NME, Melody Maker and Disc & Music Echo all had Release Me at #1 for five to seven weeks in February–April 1967, with Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields at #2 for three weeks. By contrast, for the same three weeks Melody Maker had the Beatles at #1. It is the Record Retailer chart which is now accepted as canon for the 1960–69 period, so the Melody Maker placings don’t officially count. They do however indicate that, for those three weeks at least, the sales gap between Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields and Release Me can’t have been very wide. (The big difference in total sales is to be explained by Engelbert’s record having enjoyed a much longer top ten chart run than the Beatles’ did.)

The fact remains, though, that Release Me did outsell Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields and kept it off the top spot on all but one of the UK charts. We still require an explanation of that lapse of judgement on the part of the record-buying public.

Here it is necessary to avoid a romanticised and simplistic picture of the 1960s as a uniformly hip and happening decade. The mundane reality was that, for all the new and adventurous developments in pop and rock, older and more conservative forms of popular music still retained a large audience outside of the youth demographic.

In 1967 there was much media commentary about the return of MOR ballads to the charts, but the truth is they had never gone away. Ken Dodd’s recording of the old Rudy Vallée song Tears was a huge hit in 1965, registering in third place on the OCC list of 1960s bestsellers, while the following year Jim Reeves’ Distant Drums topped the charts for five weeks and Tom Jones’ Green, Green Grass Of Home for seven. It’s also worth noting that by far the most successful LP of the mid-sixties was The Sound of Music soundtrack, which occupied the number one spot on the UK album charts for months on end, only occasionally and temporarily being dislodged from the top by new releases from the likes of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones or the Monkees. Indeed Vince Hill’s version of the saccharine Edelweiss from that musical was one of the big hits of 1967.

The Beatles’ chart dominance was in any case vulnerable to a challenge at that point. By 1967 the heyday of Beatlemania was long past and hordes of teenage fans no longer rushed out to buy the group’s latest single as soon at it arrived in the record shops. The problem was compounded by the increased sophistication of the Beatles’ musical output, which lacked the immediate commercial appeal of their early work. As the OCC list shows, sales declined accordingly. Perhaps, too, we should take account of factors that were not specific to that period in history. Then, as ever, much of popular music was simply consumed by people with tin ears and no taste.

First published on Medium in July 2023