Cynthia Weil and sixties pop

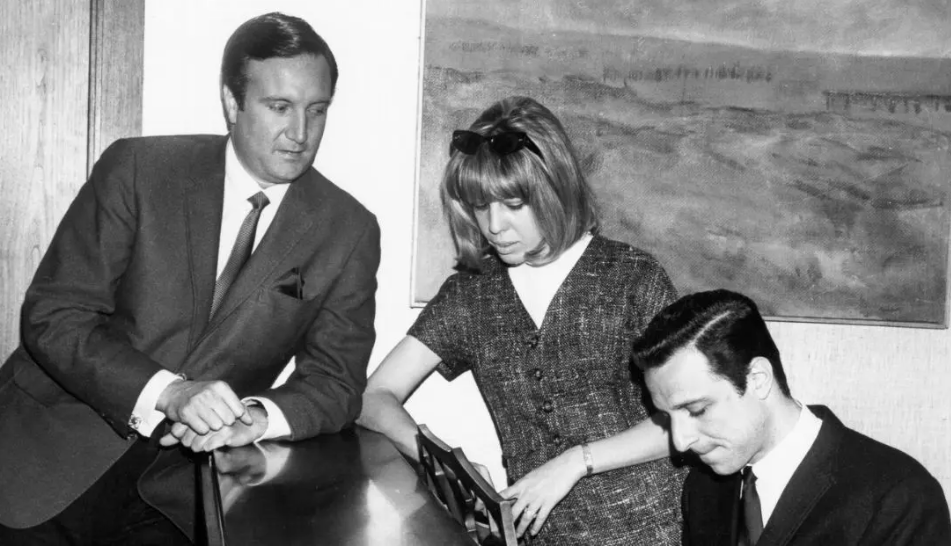

Sadly, Cynthia Weil died on 1 June, at the age of 82. With her main songwriting partner, husband Barry Mann, she was a major influence on popular music, particularly in the sixties, bringing an intelligence to lyric writing that wasn’t generally in evidence during the early part of that decade.

As part of Don Kirshner’s Brill Building team of pop composers, Cynthia could produce vacuous teen lyrics if required, but took the opportunity to introduce social commentary when she could get away with it. The Crystals’ “Uptown” from 1962 was an early example, with the singer detailing how her boyfriend is ground down by an oppressive work environment and only becomes truly human when he extracts himself from the wage labour/capital relationship and returns uptown to join her in her low-rent tenement.

(Don’t be too quick to scoff at the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts allusion. Erich Fromm’s Marx’s Concept of Man, which included substantial excerpts from the 1844 manuscripts and introduced the young Marx’s theory of alienation to a US radical readership, had been published the previous year.)

A later Mann-Weil hit issued in the Crystals’ name (although it was in fact recorded by Darlene Love and the Blossoms) was “He’s Sure the Boy I Love”. Even this more conventional girl group number still managed to subvert the genre. “He don’t hang diamonds round my neck/All he’s got’s an unemployment check” was not a typical lyric of the period.

One of Mann-Weil’s most celebrated compositions is “On Broadway”, which was a big hit in 1963 for the Drifters, as rewritten with the assistance of established songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. The protagonist is a scuffling guitar player who finds the harsh reality of life in New York a depressing contrast to its romanticised image, but declares his intention to persevere until he makes it. (“I won’t quit till I’m a star/On Broadway”.)

The original version, recorded by girl group the Cookies but not released at the time, was written from the standpoint of a young woman in a provincial town. (There was an autobiographical element to this, because Cynthia’s ambition before she hooked up with Barry was to become a writer of Broadway show tunes.) The song gently exposes the young woman’s naive illusions about the big city: “I hear the neon lights are bright on Broadway/I hear that dreams come true there every day/I hear that life don’t get you down the way it gets you in this small town/I swear I’m gonna get me there some way”. With its rather clumping drumming the Cookies’ version is musically inferior to the Drifters’ recording, but lyrically I think it’s a cut above the Leiber-Stoller rewrite.

Cynthia and Barry were supporters of the civil rights movement, and in 1963 they wrote a scathingly satirical song titled “Only in America”, which included lyrics like “Only in America, land of opportunity/Can they save a place in the back of the bus just for me”. They offered it to the Drifters. Without success. An appalled Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records listened to the song and responded: “If we release that, we’ll get lynched.”

“Only in America” was then rewritten, again with the help of Leiber-Stoller, and the lyrics toned down. The Drifters did record this revised version, which Mann-Weil were prepared to go along with because the song still retained a satirical edge. A black group singing “Only in America can a kid without a cent/Get a break and maybe grow up to be president” was rather obviously ironic, because in 1963 the prospect of an African American politician getting elected president was self-evidently absurd.

Jerry Wexler still wouldn’t accept it, though, so the recording was shelved, and was only released decades later. Instead the song was given to a white group, Jay and the Americans. This of course removed the satirical element and reduced it to a patriotic paean to upward mobility in the US. Apparently it was very popular among Cuban exiles.

Another 1963 song I like is “The Home of the Boy I Love”. This composition, which was recorded by 16-year-old actress Lori Martin, also parodies patriotic fervour, although in a distinctly less abrasive manner than “Only in America”. Paying tribute to the USA as the land where dreams come true the singer proudly declares, in a nod to Irving Berlin’s flag-waving anthem, “God bless America/The home of the boy-oy-oy I love”. (Steve Stanley’s liner notes to the Del-Fi Girl Groups collection attribute authorship to Sylvester Bradford, but a Mann-Weil demo is in circulation which calls that into question. Given the thematic similarity to “Only in America”, I think it’s reasonable to conclude that the lyrics were Cynthia’s.)

By contrast to that piece of lighthearted fluff, here is one of Cynthia and Barry’s great songs, “We Gotta Get Out of This Place”, from 1965. They had intended to offer it the Righteous Brothers, for whom they had already written “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’”, a number 1 hit the previous year. But Barry’s demo was so good that it was decided to issue it as a single in his name. Then the British record producer Mickie Most came calling, shopping around New York for songs for the Animals to record, and it was given to them instead. The Animals’ version is rightly regarded as a classic, but I think Barry’s original is much better.

The Mann-Weil composition “Kicks” is interesting. Inspired by fellow Brill Building songwriter Gerry Goffin’s mental health issues arising from his excessive use of LSD, it adopts a censorious attitude towards mind-altering substances that was not exactly universal in the sixties. (“No, you don’t need kicks/To help you face the world each day/That road goes nowhere/I’m gonna help you find yourself another way”.) “Kicks” was offered to the Animals who turned it down, possibly because Eric Burdon would have had difficulty presenting the song’s message with any conviction. Paul Revere & the Raiders had no such qualms (dress up in silly clothes, condemn drug use — they would do anything in pursuit of success) and their recording was a US hit in 1966.

In 1967 the Monkees famously ousted Don Kirshner as their musical director and took control of their own recordings. But in breaking with Kirshner himself the Monkees didn’t make the mistake of rejecting the excellent songwriters he had recruited. Headquarters, the Monkees’ first album to be recorded following the split, featured a Mann-Weil song “Shades of Gray”, which addresses the same loss of youthful ideological certainties that forms the subject of Bob Dylan’s “My Back Pages”. The arrangement, which combines Mike Nesmith’s steel guitar with overdubbed French horn and cello, sounds a bit odd to me. (Is this supposed to evoke a chamber music concert or a honky tonk in Nashville?) I prefer the earlier version by the Will-O-Bees, a now largely forgotten trio who failed to sell many records despite the backing of Cynthia and Barry.

I’ve always had a soft spot for “Shape of Things to Come”, a 1968 Mann-Weil composition that is featured in Wild in the Streets, a frankly ludicrous exploitation film based on the youth revolt of the period. It tells the story of a pop idol named Max Frost who becomes a successful politician, reduces the voting age to 14 and sends everyone over the age of 35 to a re-education camp. (In 1968 I’d have been all in favour of that. These days, rather less so.) In the course of the struggle for power Max’s followers, known as the troopers, are shot down by the cops (well, just the one cop actually — this is a low budget movie) while protesting outside the Capitol. Max responds with this stirring expression of revolutionary optimism.

In his magnum opus Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop Bob Stanley adversely compares the more cynical songwriters of the early seventies, who “seemed solely in the business of writing hits, amassing cash and investing in golfwear”, with their predecessors such as “Mann/Weil, who had been striving to make a political statement that would sell (the Crystals’ ‘Uptown’, the Animals’ ‘We’ve Got to Get Out of This Place’)”.

The degeneration described by Stanley stemmed in part from the late-sixties bifurcation of popular music that followed the rise of album-based rock. Fans of the latter tended to dismiss singles-based pop music as lightweight and unserious, and abandoned it to the teenyboppers. The market for intelligent, sophisticated pop consequently shrank considerably. (Ray Davies and the Kinks were notable victims of this phenomenon.)

Cynthia and Barry managed to ride that out, and continued to have hits, mainly in the adult contemporary field, over the subsequent decades. But it was in the sixties that they were on the cutting edge of developments in popular music. RIP Cynthia.